Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church

John 13:1-20

March 29, 2020

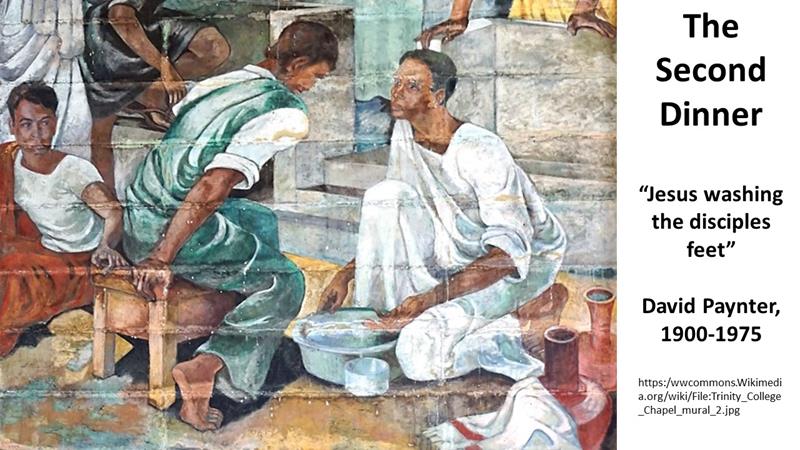

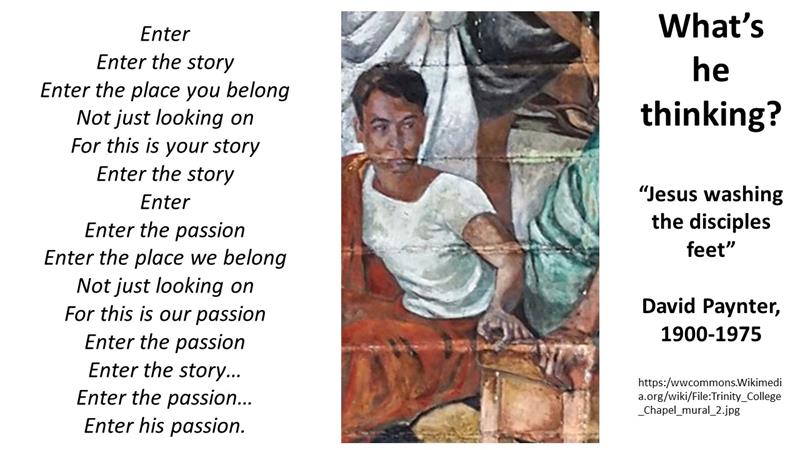

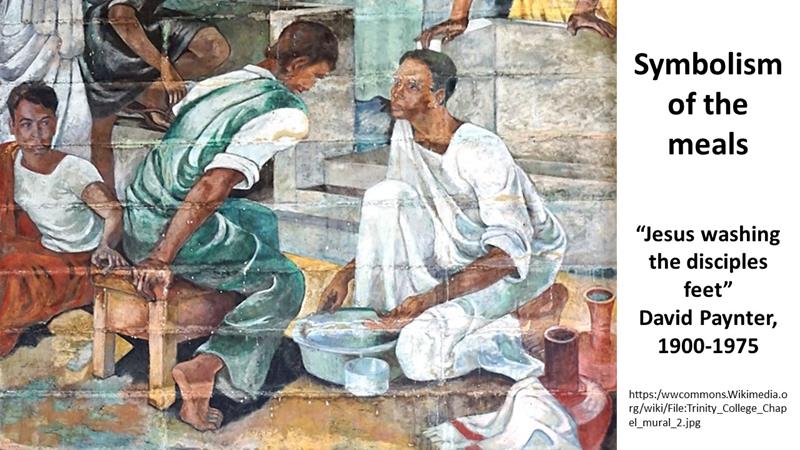

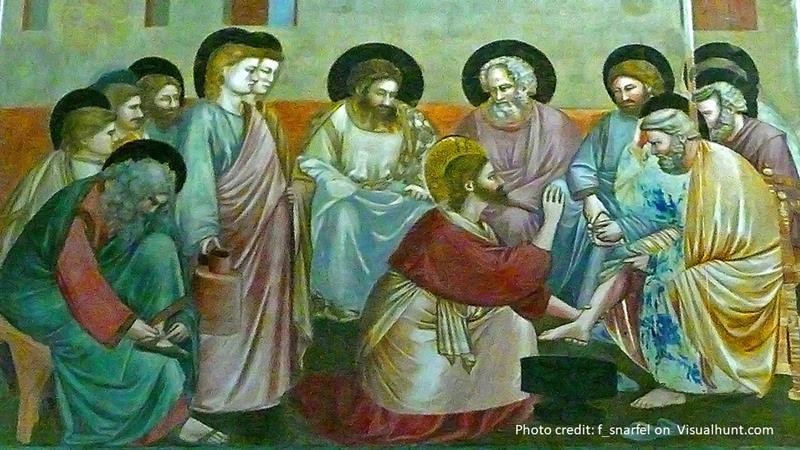

Before reading the scripture, I want us to take a look at our image for the day, which can help us get into the text. We’re looking at part of a mural by the late David Paynter titled, “Jesus washing the disciples’ feet.” The setting is along the Sri Lankan coastline. Zoom in on the guy on the left, a servant, who’s looking at what’s going on.[1] Let’s get into his head:

Jesus and the disciples have booked my master’s banquet hall. I have prepared everything according to their wishes and am ready with the water and basin as I always am. Years ago, my parents gave me to the owner as collateral for the debt they owed. But things did not go well for them, and the debt was never repaid. And so, I work to pay it off. Roman law says that someday I could be a freed person, but I will never again have the full rights in society. I’m marked as a slave for life. I keep my head down and do what the master asks because legally he has the right to punish me.

Jesus and the disciples have booked my master’s banquet hall. I have prepared everything according to their wishes and am ready with the water and basin as I always am. Years ago, my parents gave me to the owner as collateral for the debt they owed. But things did not go well for them, and the debt was never repaid. And so, I work to pay it off. Roman law says that someday I could be a freed person, but I will never again have the full rights in society. I’m marked as a slave for life. I keep my head down and do what the master asks because legally he has the right to punish me.

So, here I am with the bowl, just waiting for the go-ahead. The honored guest will be first, of course, and I know which one he is by where he’s seated. This is protocol, everyone has a place according to status. When he shows up, I recognize him and remember the stories I have heard about this teacher. He says things that upset those invested in this system of status… things like “the last shall be first.” I just can’t imagine a world like he describes.

And then he comes up to me. Smiling, he takes the basin of water from my hands. He takes my servant’s towel and wraps it around his own waist and kneels, inviting Peter to come sit. This is going to be no ordinary night. I realize my life, my view of myself and my station in life, is never going to be the same.

Sung:

Enter

Enter the story

Enter the place you belong

Not just looking on

For this is your story

Enter the story

Enter

Enter the passion

Enter the place we belong

Not just looking on

For this is our passion

Enter the passion

Enter the story…

Enter the passion…

Enter his passion.[2]

Our Scripture this morning comes from the 13th Chapter of John’s gospel. Read John 13:1-20.

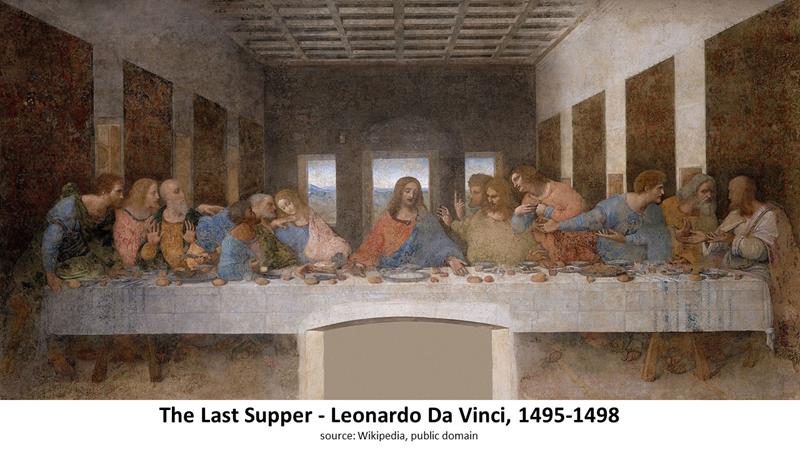

Last week we explored the first meal recorded during Jesus’ final week of earthly ministry. This is the dinner in Simon’s home interrupted by the woman with perfume anointing Jesus. Today, we’re looking at the second meal of this week. Of course, there weren’t just two meals eaten during these seven days. These are just the two recalled in the gospels. Both meals are rich with symbols. Last week, we could almost smell the expensive perfume being poured. This week, we have the bread and the wine, the foot washing, and the betrayal, all mixed in. We know this dinner as the “Last Supper” and there’s enough material here for two dozen sermons. I promise I won’t exhaust the passage.

Last week we explored the first meal recorded during Jesus’ final week of earthly ministry. This is the dinner in Simon’s home interrupted by the woman with perfume anointing Jesus. Today, we’re looking at the second meal of this week. Of course, there weren’t just two meals eaten during these seven days. These are just the two recalled in the gospels. Both meals are rich with symbols. Last week, we could almost smell the expensive perfume being poured. This week, we have the bread and the wine, the foot washing, and the betrayal, all mixed in. We know this dinner as the “Last Supper” and there’s enough material here for two dozen sermons. I promise I won’t exhaust the passage.

All four of the gospels have these stories about Jesus’ final meal with his disciples. John’s gospel, unlike Matthew, Mark and Luke, has a unique twist to it. Instead of it being the Passover, it’s the day before the Passover. You could say that in John’s gospel, they start partying early! Seriously, John wants us to think of Jesus as the Passover lamb, the one who was slain for our sins.[3] So the crucifixion occurs on Passover. The other thing John emphasizes is that there is evil lurking, but Jesus allows it to go on. It’s not like Jesus was dragged to the cross, as would have happened with most of those condemned to such a death, but that Jesus willingly gives up his life to fulfill a greater purpose. So, Jesus allows Judas to do his deed.

Interestingly, unlike the other gospels, John doesn’t recall Jesus reciting the words of the Lord’s Supper… There’s no, “This is my body broken for you…” or “This cup is the new covenant…” Instead, we’re told that as they enjoy the meal, Jesus does something strange. But before we get there, John tells us that Jesus loved the disciples to the end. Now, this can be taken that Jesus loved the disciples all along, up to this point, but there’s more here than that. It’s not merely a chronological statement, implying that up to this point in time Jesus has loved his disciples. Instead, it implies the fullness and completeness of his love. He will love them unto death, which will become clearer as the events of the night and next day unfolds.

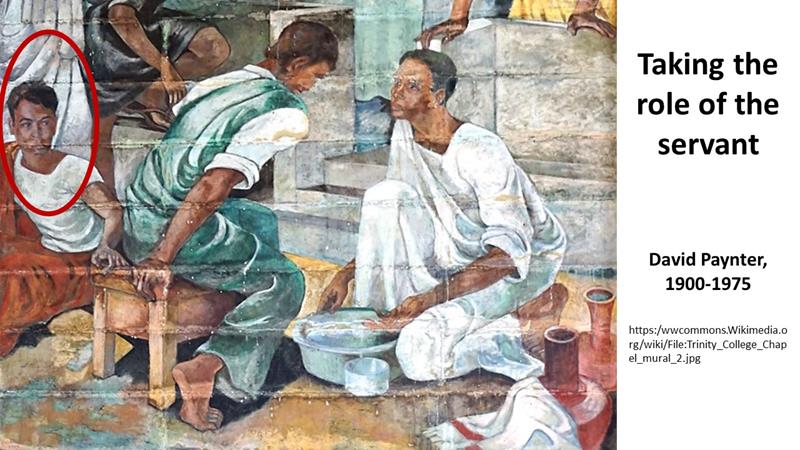

Jesus then assumes the role of the servant. For those of us living on this side of the resurrection, we immediately think of Paul’s “Christ Hymn” in Philippians, where we’re told that “Christ emptied himself, taking the form of a slave.”[4] Like a servant, like the dude in the picture whose job this should have been, Jesus goes around the table with a basin and washes the disciples’ feet. This is an example of extreme humility and sets up the rest of our reading. There are two implications of Jesus’ action. The first, which is covered in verses 6 to 11, is theological. This deals with our relationship to God. The second, covered in verses 12-20 is ethical. It focuses on how we relate to others.[5] Let’s look at each.

Peter has a problem with what Jesus is doing. In his book, this is just not right. The Master shouldn’t wash the dirty feet of the disciples. But Jesus not only offers to do this, he insists that he must. In verse 8, Jesus says that if he doesn’t wash Peter’s feet, he’ll have no share in him. The Gospel is summarized in this short sentence. We must be open to Jesus taking on our sins, washing them away, if we want to be in fellowship with him. This is the theological part of this passage. If we think we are too good or to dirty for Jesus to wash our feet, we won’t be able to share in his free grace.[6] Jesus freely takes up the towel and basin, just as he freely takes up the cross, and we have to accept him. Theologically, if we are not open to God doing for us what we can’t do for ourselves, we can’t experience grace.

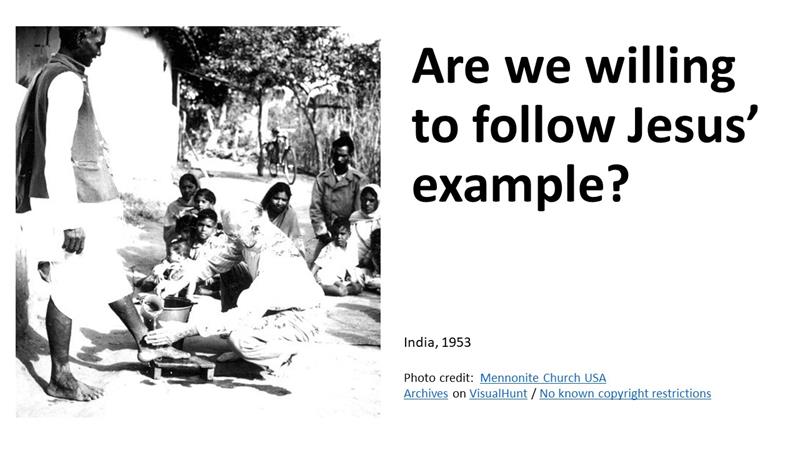

The second implication of the foot washing is ethical. “I’ve done this for you,” Jesus says, “so you need to do it to one another.” Jesus has shown us how to live our lives. We are called to live in mutual service, showing submission to one another, being willing to forgive when we are wronged, and having patience. All these traits, Jesus demonstrated. We too must learn from the Master. We must be willing to follow his example.

The second implication of the foot washing is ethical. “I’ve done this for you,” Jesus says, “so you need to do it to one another.” Jesus has shown us how to live our lives. We are called to live in mutual service, showing submission to one another, being willing to forgive when we are wronged, and having patience. All these traits, Jesus demonstrated. We too must learn from the Master. We must be willing to follow his example.

So how do we live this way at a time when we’re called to keep our social distance for the sake of society? Obviously, Jesus wasn’t worried about COVID-19 when he washed the feet of his disciples, and these days we’re told, again and again, to be sure to wash our own hands. We are living in a unique time. After all, we been called to sit on the couch and watch TV as if that’s a sacrifice. But we got to do more. We are still the church deployed in the world.

Who wasn’t moved by the story of the priest in Italy whose parishioners purchased him a respirator? But the priest insisted the respirator be used on a child who was ill.[7] He died. That’s showing the extreme side of what Jesus is talking about here.

But there are other things we all need to be doing. Staying away from others and isolating ourselves will help slow this disease. With the marvels of technology, we can still be connected through the phone and over the internet. And don’t forget the U. S. mail. The Session and Pastors of this church have made a commitment to call every member every week through this crisis. If you don’t get a call, let me know. We’ll see to it that you are included. And you can join us in calling and checking in on one another. After all, we do have new directories that are well suited for this. There are those who live by themselves and are lonely. Let’s do what we can to stay connected. We can also uphold one another in our prayers. We can write letters of encouragement. We can still be supportive of organizations that are making sure the most vulnerable in our communities are safe and cared for during this scary time. Did you know that this congregation collected 190 pairs of socks on the last day we were able to meet in worship? This Monday, those socks will be taken to Union Mission to be distributed.

Finally, we’re living in a time when we should be extremely grateful for others. Think of the sacrifices others are making, as they assume the role of the servant. Those work in the hospital, whether they are doctors and surgeons or the cleaning staff, they’re on the front line for us. And how about those who work in the club here at the Landings, working hard to get for food and groceries to us. Those who pick up our trash. And don’t forget the grocery workers, those in the shipping industry, those making masks and gowns for the medical profession. At a time like this, we need to remember all these people we depend on and be thankful and grateful.

Jesus comes before us at the table, with a towel wrapped around his waist and a basin. He kneels. Do we let him wash our feet? And, if so, are we willing to humble ourselves and serve others in the manner that he has served us? These are questions we need to ask ourselves. Amen.

Jesus comes before us at the table, with a towel wrapped around his waist and a basin. He kneels. Do we let him wash our feet? And, if so, are we willing to humble ourselves and serve others in the manner that he has served us? These are questions we need to ask ourselves. Amen.

©2020

[1] A copy of this mural is in the “Art in the Christian Tradition” collection at Vanderbilt Divinity Library in Nashville, Tennessee. The original is in Trinity College.

[2] This edited monologue and song is from the Worship Design Series: “Entering the Passion of Jesus: Picturing Ourselves in the Story.” Subscription from www.worshipdesignstudio.com.

[3] This image of Jesus as the Passover lamb becomes clearer in John’s revelation. See Revelation 5:12 and 6:1.

[4] Philippians 2:7.

[5] Frederick Dale Bruner, The Gospel of John: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MIhigan: Eerdmans,2012), 749.

[6] Bruner, 765.

[7] https://nypost.com/2020/03/24/italian-priest-dies-of-coronavirus-after-giving-respirator-to-younger-patient/

S. C. Gwynne, Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion, and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson (New York: Scribner, 2014), 672 pages including appendix, notes, bibliography, maps. There are eight pages of black and white photos.

S. C. Gwynne, Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion, and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson (New York: Scribner, 2014), 672 pages including appendix, notes, bibliography, maps. There are eight pages of black and white photos.

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison  None of us are happy with the way things are going in Jerusalem. It’s not just the political oppression. We’re troubled by the dire situation of the hungry, the poor, the sick, and the disturbed. The Roman’s don’t’ care about them? At least we try. Every penny we scrape up we try to pass on to those who need it. Before Jesus arrived for dinner, some of us were also wondering if we should save some money in case we needed to hide out in the not-too-distant future.

None of us are happy with the way things are going in Jerusalem. It’s not just the political oppression. We’re troubled by the dire situation of the hungry, the poor, the sick, and the disturbed. The Roman’s don’t’ care about them? At least we try. Every penny we scrape up we try to pass on to those who need it. Before Jesus arrived for dinner, some of us were also wondering if we should save some money in case we needed to hide out in the not-too-distant future.

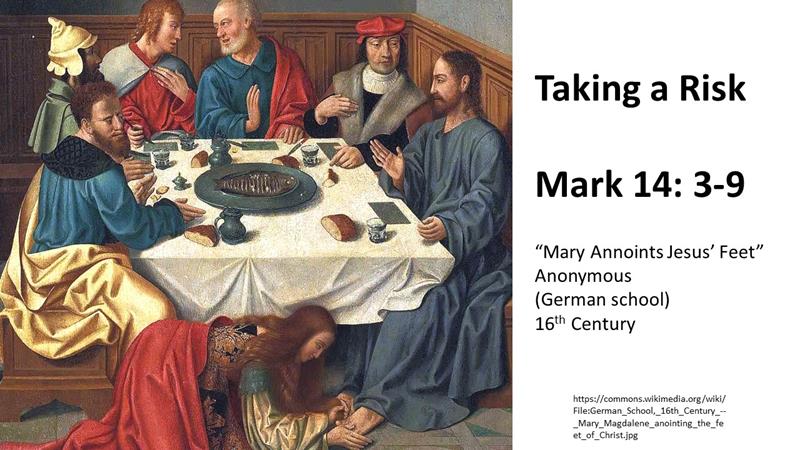

There are two big meals highlighted in the final week of Jesus’ earthly ministry.

There are two big meals highlighted in the final week of Jesus’ earthly ministry.

Now consider the risks this woman takes. She shows up uninvited. She shocks the guests with her generosity. Ever give a gift and wonder and worry if it would be accepted? Her gift does upset those around the table. Why isn’t this money being given to the poor? They ask. Jesus’ protects her dignity, saying she’ll be remembered because of what she’s done. And Jesus doesn’t stop there. He goes on to say we’ll always have the poor, but he won’t be around long, at least not in person.

Now consider the risks this woman takes. She shows up uninvited. She shocks the guests with her generosity. Ever give a gift and wonder and worry if it would be accepted? Her gift does upset those around the table. Why isn’t this money being given to the poor? They ask. Jesus’ protects her dignity, saying she’ll be remembered because of what she’s done. And Jesus doesn’t stop there. He goes on to say we’ll always have the poor, but he won’t be around long, at least not in person. In Matthew’s gospel, we’re told that helping the poor and needy, the sick and the prisoner, is the same as helping Christ,

In Matthew’s gospel, we’re told that helping the poor and needy, the sick and the prisoner, is the same as helping Christ, What can we do? We certainly can’t heal the world, just as the woman couldn’t keep Jesus off the cross. But what kind of risk might we take for Jesus? Things are changing so rapidly around us. It’s scary. But we need to remember, this is not the first time Christ’s church has witnessed pestilence. In the 14th Century, a large percentage of the population died from the plague, but at the same time Great Cathedrals were being built.

What can we do? We certainly can’t heal the world, just as the woman couldn’t keep Jesus off the cross. But what kind of risk might we take for Jesus? Things are changing so rapidly around us. It’s scary. But we need to remember, this is not the first time Christ’s church has witnessed pestilence. In the 14th Century, a large percentage of the population died from the plague, but at the same time Great Cathedrals were being built. This woman might be seen as a fool for Christ. She faced ridicule, but Jesus protected her dignity and honored her. Don’t be afraid to be a fool for Christ. For our Master will take care of us. Amen.

This woman might be seen as a fool for Christ. She faced ridicule, but Jesus protected her dignity and honored her. Don’t be afraid to be a fool for Christ. For our Master will take care of us. Amen.

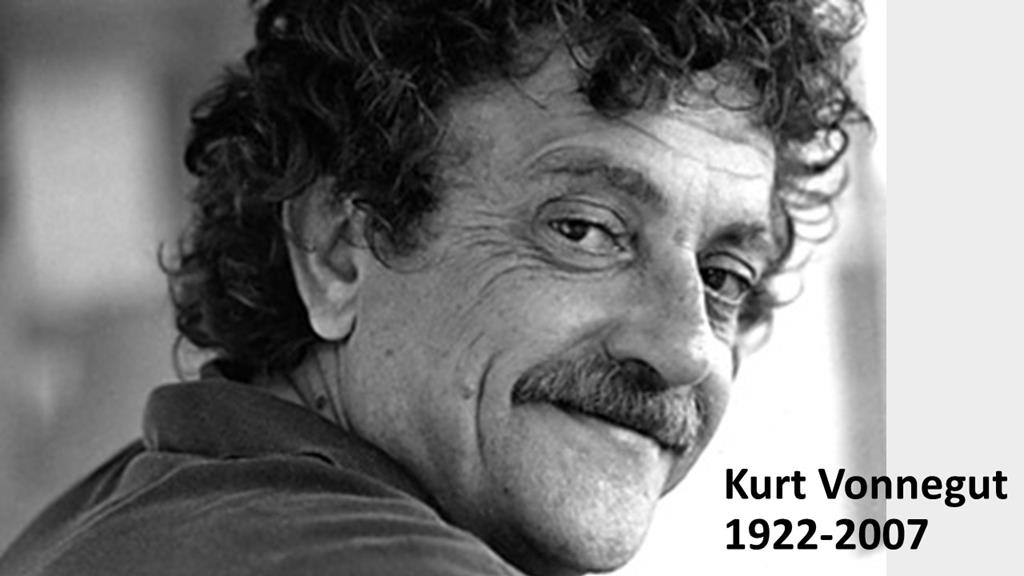

If you read the entirety of Matthew 22 (and with the extra time we may be having on hand as everything is being cancelled because of the Coronavirus, it’s not a bad idea), you’d witness a masterful campaign to trap Jesus. But Jesus isn’t so easy to catch. He’s kind of like Stonewall Jackson in the Valley Campaign in the spring of 1862. Jackson faced much larger armies who wanted to trap and do him in.

If you read the entirety of Matthew 22 (and with the extra time we may be having on hand as everything is being cancelled because of the Coronavirus, it’s not a bad idea), you’d witness a masterful campaign to trap Jesus. But Jesus isn’t so easy to catch. He’s kind of like Stonewall Jackson in the Valley Campaign in the spring of 1862. Jackson faced much larger armies who wanted to trap and do him in. What’s happened is that unlikely groups join together to challenge Jesus. The old cliché, “politics make strange bedfellows,” rings true. Groups who wouldn’t normally give each other the time of day have come together to take on Jesus. They sense that Jesus is challenging the existing order. You have a few Herodians, who are Jews who believe they’re be better off cooperating with the Romans. They take their name from Herod, who had Jewish blood but worked for the Empire. And you have the Pharisees; a group of seriously committed religious leaders who believe in the resurrection. Theologically, they’re most like Jesus, but Jesus constantly challenges them and exposes their hypocrisy.

What’s happened is that unlikely groups join together to challenge Jesus. The old cliché, “politics make strange bedfellows,” rings true. Groups who wouldn’t normally give each other the time of day have come together to take on Jesus. They sense that Jesus is challenging the existing order. You have a few Herodians, who are Jews who believe they’re be better off cooperating with the Romans. They take their name from Herod, who had Jewish blood but worked for the Empire. And you have the Pharisees; a group of seriously committed religious leaders who believe in the resurrection. Theologically, they’re most like Jesus, but Jesus constantly challenges them and exposes their hypocrisy. What we read this morning could be described as one movement in a tag-team wrestling match. The Herodians and the Pharisees team up on Jesus.

What we read this morning could be described as one movement in a tag-team wrestling match. The Herodians and the Pharisees team up on Jesus. So what is Jesus telling us in this passage? Do you remember those big posters that use to sit out in front of the Post Office and government buildings with Uncle Sam pointing his finger and saying: “I want you!” I believe we could easily surmise this text into a big poster of God saying: “I want you!”

So what is Jesus telling us in this passage? Do you remember those big posters that use to sit out in front of the Post Office and government buildings with Uncle Sam pointing his finger and saying: “I want you!” I believe we could easily surmise this text into a big poster of God saying: “I want you!” “Tell me,” they ask, “Is it lawful to pay taxes to the emperor, or not?” Jesus has to be careful. Last week you heard Deanie preach about the revolutionary act of Jesus cleaning the temple. Now they want Jesus to make a revolutionary statement against the civil authorities. If Jesus says they should not pay taxes, the Herodians could have him arrested for treason. But then, if he says to pay the taxes, the Pharisees can attack him for not being a patriotic Jew.

“Tell me,” they ask, “Is it lawful to pay taxes to the emperor, or not?” Jesus has to be careful. Last week you heard Deanie preach about the revolutionary act of Jesus cleaning the temple. Now they want Jesus to make a revolutionary statement against the civil authorities. If Jesus says they should not pay taxes, the Herodians could have him arrested for treason. But then, if he says to pay the taxes, the Pharisees can attack him for not being a patriotic Jew. Jesus asks them for a coin. Unlike us, he didn’t have to worry about where that’s coin has been or picking up some a virus from its surface. However, Jesus still has to be careful. The disciples, we know, had a common purse and he could have gone there to fetch a coin, but then the Pharisees might have charged him with toting around an engraved image of the emperor.

Jesus asks them for a coin. Unlike us, he didn’t have to worry about where that’s coin has been or picking up some a virus from its surface. However, Jesus still has to be careful. The disciples, we know, had a common purse and he could have gone there to fetch a coin, but then the Pharisees might have charged him with toting around an engraved image of the emperor. Give to God what is God’s. This phrase is often overlooked. We tend to get hung up on what is Caesar’s and what is ours. We get hung up on the petty details and we miss the important question. What does it mean for us to give ourselves to God?

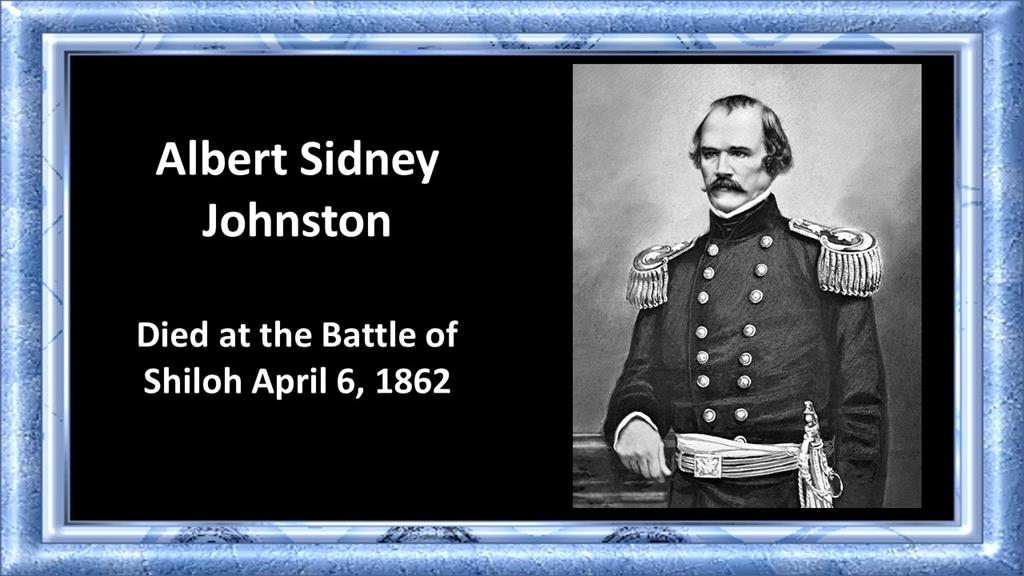

Give to God what is God’s. This phrase is often overlooked. We tend to get hung up on what is Caesar’s and what is ours. We get hung up on the petty details and we miss the important question. What does it mean for us to give ourselves to God? Earlier I mentioned Stonewall Jackson, whose biography I’m currently reading. But let me tell you two other Civil War stories, they’re both short, and demonstrate this point. At the Battle of Shiloh in the spring of 1862, Albert Sidney Johnson led the Confederate troops as they overwhelmed the Union forces near Pittsburg Landing along the Tennessee River. It was a bloody day and the Union lines were broken in places. During a lull in the first day of battle, Johnson, seeing a number of wounded Union soldiers in need, ordered his surgeon to set up an aid station and to tend to their needs. According to Shelby Foote in his novel about the battle, his surgeon, Dr. Yandell protested. Johnson cut him off saying “These men were our enemies a moment ago. They are our prisoners now. Take care of them.” A few minutes later, a stray bullet struck Johnson’s leg and without medical aid, he quickly bled to death.

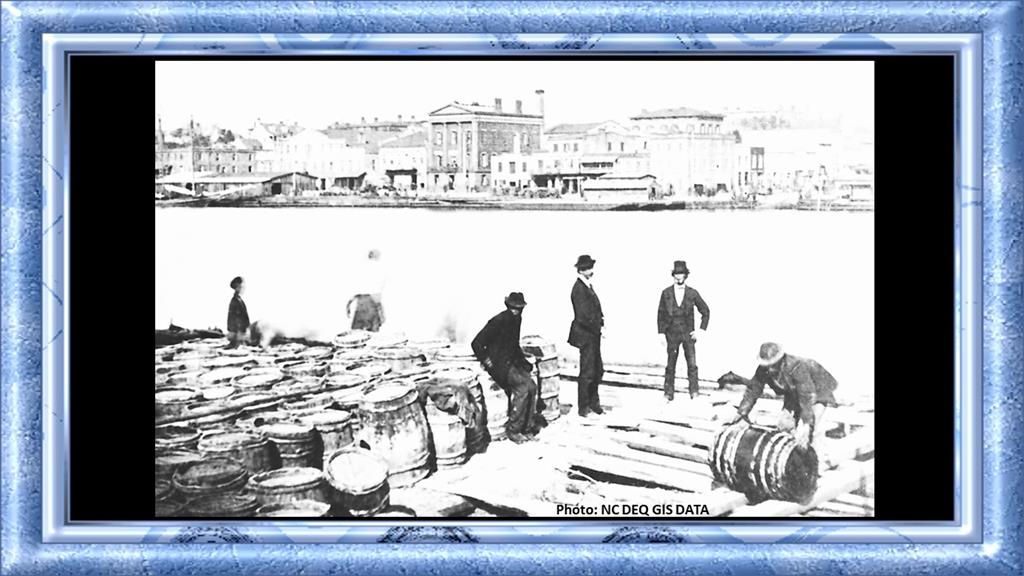

Earlier I mentioned Stonewall Jackson, whose biography I’m currently reading. But let me tell you two other Civil War stories, they’re both short, and demonstrate this point. At the Battle of Shiloh in the spring of 1862, Albert Sidney Johnson led the Confederate troops as they overwhelmed the Union forces near Pittsburg Landing along the Tennessee River. It was a bloody day and the Union lines were broken in places. During a lull in the first day of battle, Johnson, seeing a number of wounded Union soldiers in need, ordered his surgeon to set up an aid station and to tend to their needs. According to Shelby Foote in his novel about the battle, his surgeon, Dr. Yandell protested. Johnson cut him off saying “These men were our enemies a moment ago. They are our prisoners now. Take care of them.” A few minutes later, a stray bullet struck Johnson’s leg and without medical aid, he quickly bled to death. A second story comes from the city of Wilmington during the Civil War. In 1862, a blockade runner that had come in from the Caribbean brought Yellow Fever to the town. Those who could fled to the country, but several of the pastors and the leading citizens of the town stayed behind, feeling it was their Christian obligation to help out the victims. Over 400 people died of Yellow Fever that fall, including many of those who intentionally stayed to care for the dying.

A second story comes from the city of Wilmington during the Civil War. In 1862, a blockade runner that had come in from the Caribbean brought Yellow Fever to the town. Those who could fled to the country, but several of the pastors and the leading citizens of the town stayed behind, feeling it was their Christian obligation to help out the victims. Over 400 people died of Yellow Fever that fall, including many of those who intentionally stayed to care for the dying. Give to God what is God’s, is the message here. So yes, we should pay our income tax. And when you write that check this April, we might remember that giving Caesar his due can be a lot easier than giving to God what is his. For our whole life belongs to God. But then, God’s given us life and in Jesus Christ has redeemed us to be his people. That’s a debt we can’t repay, nor is such repayment expected. As the old hymn goes, “Jesus paid it all.”

Give to God what is God’s, is the message here. So yes, we should pay our income tax. And when you write that check this April, we might remember that giving Caesar his due can be a lot easier than giving to God what is his. For our whole life belongs to God. But then, God’s given us life and in Jesus Christ has redeemed us to be his people. That’s a debt we can’t repay, nor is such repayment expected. As the old hymn goes, “Jesus paid it all.”

W. Singer and Emerson T. Brooking, LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media (2018, Mariner Books, Boston, 2019), 407 pages including index and notes plus eight pages of photos.

W. Singer and Emerson T. Brooking, LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media (2018, Mariner Books, Boston, 2019), 407 pages including index and notes plus eight pages of photos.

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

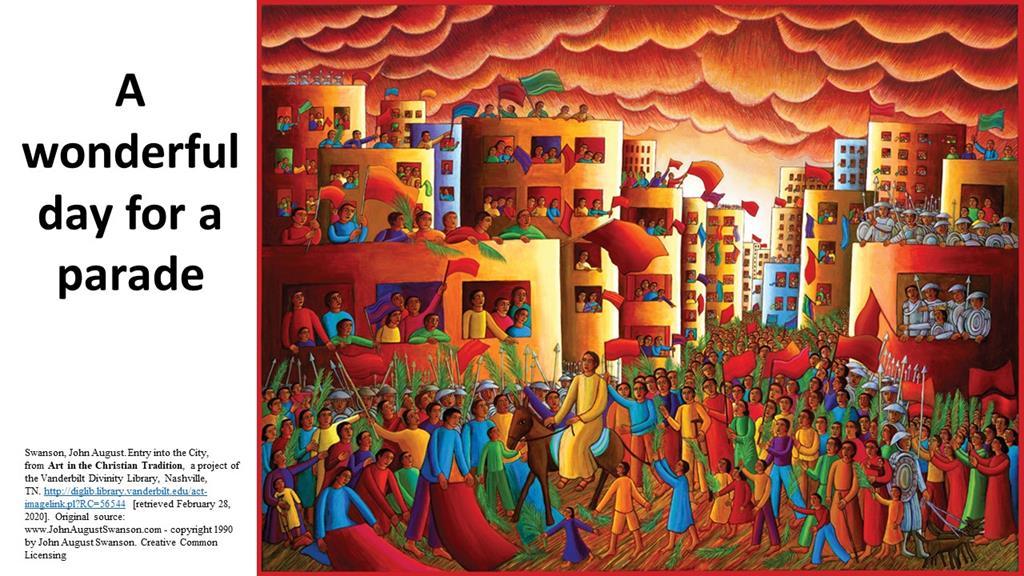

The disciples, without being asked, placed their cloaks on the animals as a saddle. Now, how Jesus rode two animals, as Matthew seems to suggest, we’re not told. We might image him, holding the reigns in his teeth, with a foot on each animal, like a circus rider taking a victory lap, but that’s probably not the case. Instead, he may have sat on the donkey, sidesaddle, as was the custom for riding such beasts, and had the colt follow along, staying close to its mother.

The disciples, without being asked, placed their cloaks on the animals as a saddle. Now, how Jesus rode two animals, as Matthew seems to suggest, we’re not told. We might image him, holding the reigns in his teeth, with a foot on each animal, like a circus rider taking a victory lap, but that’s probably not the case. Instead, he may have sat on the donkey, sidesaddle, as was the custom for riding such beasts, and had the colt follow along, staying close to its mother. Quickly, as he and the disciples approach the city’s walls, excitement builds. Followers start placing their cloaks on the ground—in Sir Walter Raleigh’s fashion—as the procession begins. Someone brings in branches—we’re not told if they’re palms (the palms only appear in John’s gospel).

Quickly, as he and the disciples approach the city’s walls, excitement builds. Followers start placing their cloaks on the ground—in Sir Walter Raleigh’s fashion—as the procession begins. Someone brings in branches—we’re not told if they’re palms (the palms only appear in John’s gospel). I image its mostly pilgrims making up the crowd. Many of them would have been from the small towns and villages in Galilee, who’ve come to Jerusalem to celebrate the Passover. This is Spring Break, 30 AD. Just like today, most everyone makes a trek south—but instead of Florida, they head to Jerusalem. For many of the pilgrims, this is the highlight of their life—being in Jerusalem for the holiday. It’s like us getting a chance to celebrate New Year’s Eve on Times’ Square, Mardi Gras in New Orleans, or Christmas at Grandma Moses’ farm. This is a once in a lifetime chance. And as they come to Jerusalem, they recall God’s great acts of salvation in the past, of how God freed the Hebrew people from Egyptian slavery and saved them from Pharaoh’s army. Reminiscing about God’s past activity opens them up to the possibility God will act again and restore Israel to her former glory. They’ve gathered in hope.

I image its mostly pilgrims making up the crowd. Many of them would have been from the small towns and villages in Galilee, who’ve come to Jerusalem to celebrate the Passover. This is Spring Break, 30 AD. Just like today, most everyone makes a trek south—but instead of Florida, they head to Jerusalem. For many of the pilgrims, this is the highlight of their life—being in Jerusalem for the holiday. It’s like us getting a chance to celebrate New Year’s Eve on Times’ Square, Mardi Gras in New Orleans, or Christmas at Grandma Moses’ farm. This is a once in a lifetime chance. And as they come to Jerusalem, they recall God’s great acts of salvation in the past, of how God freed the Hebrew people from Egyptian slavery and saved them from Pharaoh’s army. Reminiscing about God’s past activity opens them up to the possibility God will act again and restore Israel to her former glory. They’ve gathered in hope. We’re left to wonder what our response would have been if we were there? Where would we be in this story? Would we have been in the crowds shouting “Hosanna?” And if so, would we’ve also been in the crowds shouting “Crucify?” For you see, it’s hard to separate the parade at the beginning of Holy Week, with the crucifixion that comes five days later.

We’re left to wonder what our response would have been if we were there? Where would we be in this story? Would we have been in the crowds shouting “Hosanna?” And if so, would we’ve also been in the crowds shouting “Crucify?” For you see, it’s hard to separate the parade at the beginning of Holy Week, with the crucifixion that comes five days later. Jesus takes a risk with this parade. In this series we’re going to see repeatedly the risks Jesus and the disciples took during Holy Week. Here, with the parade, Jesus mocks politicians who entered Jerusalem with pomp and circumstance. As Jesus comes into Jerusalem, there were two other significant political figures either already in the city (or if not, they were soon to be there): Pilate, the Roman governor, and Herod, the Roman puppet king. There was probably a parade for them too, one involving fancy horses and soldiers with shiny brass and perhaps even a band. Pilate and Herod display the power of Empire; Jesus, humbly riding on a donkey, displays the power of a mysterious kingdom, one not of this world. Who do we follow? Are we lured by the fancy horses and war chariots of the kings and politicians? Or do we follow the man on a donkey.

Jesus takes a risk with this parade. In this series we’re going to see repeatedly the risks Jesus and the disciples took during Holy Week. Here, with the parade, Jesus mocks politicians who entered Jerusalem with pomp and circumstance. As Jesus comes into Jerusalem, there were two other significant political figures either already in the city (or if not, they were soon to be there): Pilate, the Roman governor, and Herod, the Roman puppet king. There was probably a parade for them too, one involving fancy horses and soldiers with shiny brass and perhaps even a band. Pilate and Herod display the power of Empire; Jesus, humbly riding on a donkey, displays the power of a mysterious kingdom, one not of this world. Who do we follow? Are we lured by the fancy horses and war chariots of the kings and politicians? Or do we follow the man on a donkey.

As we move through this season of Lent, we need to ponder what Jesus’ risked during Holy Week, and what we are willing to risk for the sake of the gospel.

As we move through this season of Lent, we need to ponder what Jesus’ risked during Holy Week, and what we are willing to risk for the sake of the gospel. We hear the crowds… We are drawn toward Jesus… Will we just hang around for the fun of the parade, or will we take a risk and continue to follow him as his journey moves toward the cross upon which we’ll be called to sacrifice our wills and desires for his? Amen

We hear the crowds… We are drawn toward Jesus… Will we just hang around for the fun of the parade, or will we take a risk and continue to follow him as his journey moves toward the cross upon which we’ll be called to sacrifice our wills and desires for his? Amen Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

This all amazes the disciples and causes Peter to begin babble about building shelters, perhaps to prolong the event. But while Peter rambles, we’re told a bright cloud suddenly overshadowed them. Think about this, Jesus is already dazzling white, so this cloud must have been really amazing. And from the cloud, as it was at Jesus’ baptism, God speaks. “This is my Son, the Beloved; with him I am well pleased; listen to him.” The words are the same as at Jesus’ baptism except for the last three: “Listen to him.”

This all amazes the disciples and causes Peter to begin babble about building shelters, perhaps to prolong the event. But while Peter rambles, we’re told a bright cloud suddenly overshadowed them. Think about this, Jesus is already dazzling white, so this cloud must have been really amazing. And from the cloud, as it was at Jesus’ baptism, God speaks. “This is my Son, the Beloved; with him I am well pleased; listen to him.” The words are the same as at Jesus’ baptism except for the last three: “Listen to him.”

So what does the Transfiguration say to us today? Jesus is Lord, listen to him, obey him, trust him, follow him, and don’t be afraid. “Get up, don’t be afraid.” Good words for us to consider as we, as a congregation, prepare for our future. Amen.

So what does the Transfiguration say to us today? Jesus is Lord, listen to him, obey him, trust him, follow him, and don’t be afraid. “Get up, don’t be afraid.” Good words for us to consider as we, as a congregation, prepare for our future. Amen. Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison  Today, we’re looking at walking. In a way, the ability to walk is what makes us human. In Genesis, we have that beautiful image of God walking in the garden and wanting the man and woman to join the stroll.

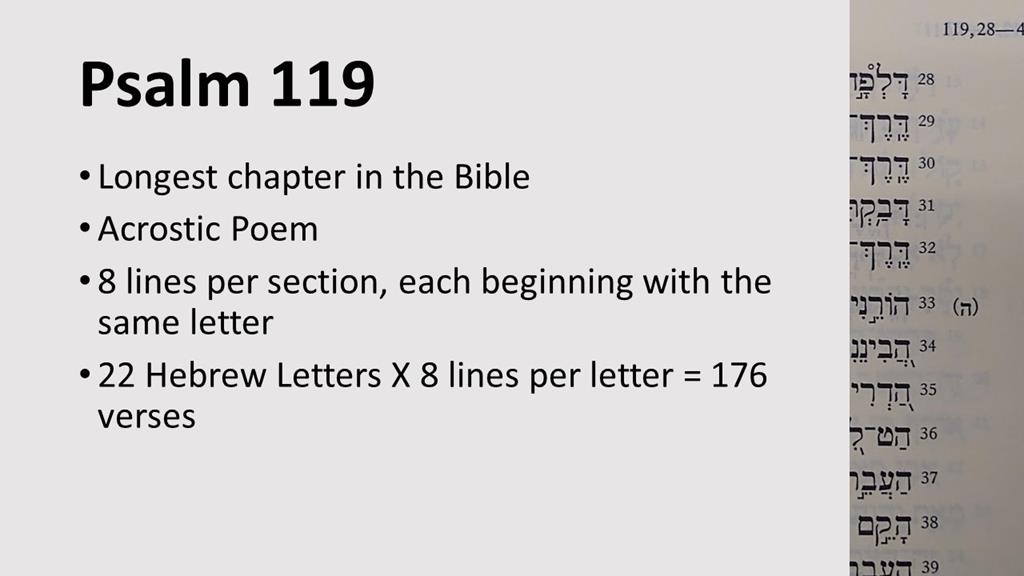

Today, we’re looking at walking. In a way, the ability to walk is what makes us human. In Genesis, we have that beautiful image of God walking in the garden and wanting the man and woman to join the stroll. Before reading our last passage, from Psalm 119, let me share a bit about this mega-Psalm. You might know that this Psalm is the longest chapter in the Bible. There are 176 verses to the 119th Psalm. It’s way too much to preach on in one sermon! But it’s also a unique. I know you’ve heard me speak of acrostic Psalms… This is a type of poetry where every line begins with the next letter in the alphabet. In English, it would be like writing, “Apples are red, Berries are blue, Cats are cute… etc. Using an acrostic method helps in memorization. I’ll come back to this later in the sermon.

Before reading our last passage, from Psalm 119, let me share a bit about this mega-Psalm. You might know that this Psalm is the longest chapter in the Bible. There are 176 verses to the 119th Psalm. It’s way too much to preach on in one sermon! But it’s also a unique. I know you’ve heard me speak of acrostic Psalms… This is a type of poetry where every line begins with the next letter in the alphabet. In English, it would be like writing, “Apples are red, Berries are blue, Cats are cute… etc. Using an acrostic method helps in memorization. I’ll come back to this later in the sermon.

Of course, we’re not just to walk for walking sake, even though it is good for our physical being. Scripture tells us repeatedly to walk in the ways of the Lord. Psalm 119 is a meditation on God’s law. Throughout this passage, we’re encouraged to walk in the law, to walk in the ways of God, to let God’s law light the path for our feet.

Of course, we’re not just to walk for walking sake, even though it is good for our physical being. Scripture tells us repeatedly to walk in the ways of the Lord. Psalm 119 is a meditation on God’s law. Throughout this passage, we’re encouraged to walk in the law, to walk in the ways of God, to let God’s law light the path for our feet. But I also want you to join in on another walk, one that will involve all the congregation. As you know, next Sunday we’re going to lay out a new Strategic Plan for our congregation. We want to be a “joyful, thriving church reflecting the face of Jesus to the world!” Our mission is to “Love God, Love our Neighbors, and to Change the world.” We have set up core values (using an acrostic formation-kind of like Psalm 119-that spells out WORSHIP). These core values demonstrate God’s love by Welcoming, Offering, Respecting, Serving, Helping, Investing, and Praying. All this is supported by four pillars, which we as a church need to walk within. These pillars will require each of us to commit ourselves to excellence, and we if bind ourselves on this journey together, we will live into our Vision and Mission.

But I also want you to join in on another walk, one that will involve all the congregation. As you know, next Sunday we’re going to lay out a new Strategic Plan for our congregation. We want to be a “joyful, thriving church reflecting the face of Jesus to the world!” Our mission is to “Love God, Love our Neighbors, and to Change the world.” We have set up core values (using an acrostic formation-kind of like Psalm 119-that spells out WORSHIP). These core values demonstrate God’s love by Welcoming, Offering, Respecting, Serving, Helping, Investing, and Praying. All this is supported by four pillars, which we as a church need to walk within. These pillars will require each of us to commit ourselves to excellence, and we if bind ourselves on this journey together, we will live into our Vision and Mission.