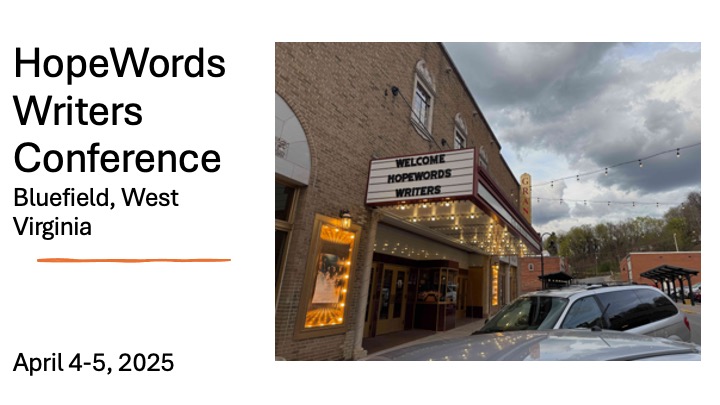

For those of you who wonder why I didn’t post a sermon on Sunday, it’s because I didn’t preach. I was recovering from a stomach bug and was still in the “infectious stage.” I doubt anyone wanted to risk seeing me. It all started late Wednesday night when I became violently sick and between episodes, was unable to maintain my blood sugar levels. I ended up in the ER, receiving IV fluids and shots to control nausea. After 4 hours, I came home but as late as Friday was experiencing diarrhea. As I was to have 48 hours after the last symptom, I was blessed to have someone else preach for me. The next sermon, God willing, will be posted on April 11th. This week, I had planned to be off in order to attend the HopeWords Writer’s Conference in Bluefield. Hopefully, you’ll find an interesting book or two from those books I finished reading during March.

Jon Meacham, His Truth is Marching On: John Lewis and the Power of Hope with Afterword by John Lewis

(New York: Penguin Random House, 2020), 354 pages including note, bibliography, and an index.

In a way, Meacham’s biography on John Lewis reads like a spiritual memoir. Meacham provides the details of Lewis’ early life. However, his real focus is on Lewis’ faith and how it helped him as a young leader of the Civil Rights Movement.

Lewis wanted to preach from an early age. The family’s chicken coop became his church. He preached to the birds and took offense when his mother cooked one of his “parishioners.” Throughout this book, Meacham captures the theological themes of Lewis’ life. These include love in the face of hate, non-violence, and with Martin Luther King, a vision of a beloved community.

This book mostly focuses on Lewis’ first 28 years, until the death of Martin Luther King in 1968. A long epilogue brings the reader up to date on Lewis later work. This includes his 17 terms in the United States Congress. Following this is an afterword, written by Lewis himself, before his death on July 17, 2020. The book was published later that year.

Jon Meacham, as a young reporter for The Chattanooga Times, met Lewis on election night, 1992. He had just won his fourth term in Congress and Clinton had beaten George H. W. Bush for the Presidency. They would meet many more times over the years. Meacham began working on this book toward the end of Lewis’ life. Even thought Meacham focuses on Lewis’ work before they met, the closeness of the preacher/politician with the author is sensed throughout this book.

Lewis’ grandfather was born a slave. But after Civil War, he worked hard and brought land. Lewis’ own father was a tenant farmer, but the family seldom saw the white owner of the land they worked. Lewis himself saw few white people in his early life, living in a segregated world. In 1951, at age 11, this changed one summer when an uncle took him to Buffalo, New York. It was an eye-opening event for Lewis.

The 1950s were a time of change and uncertainty in the South. For African Americans, there was a bright light when the Supreme Court ruling against school segregation in 1954. Of course, nothing changed fast. But it was also a time of lynchings and the torture death of Emmett Till, a boy from Chicago close to Lewis’ age.

For young Lewis, another change came when he started listening to the Martin Luther King, Jr. preaching on the radio. In 1957, Lewis left his hometown for American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee. The small school trained African American men for the ministry. While a student, Lewis learned about non-violent protests and participated in sit-ins at local cafes. He even volunteer to attempt to integrate a local white university. He was invited to meet with Martin Luther King, Jr. and Ralph Abernathy, who suggested he needed his parents’ approval since he was not yet 18 years of age. They refused and Lewis returned to the seminary. He continued his involved in non-violence as he participated as a Freedom Bus Rider. In all these experiences, Lewis saw the brutality of the Southern Whites as they resisted the demands of Black Southerners.

As a young man, Lewis quickly became a leader within the Civil Rights movement. Even before his brutal beating on the Emmett Pettit bridge in Selma, Alabama in 1965, he had be with other leaders meeting President Johnson in the White House. It’s amazing that Lewis could continue to advocate non-violence and envison a beloved community with the violence he experienced. But he did. He even had to resist others within the movement, especially after Selma and later the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. These events led many to call for violence and Black Power as a way to confront the White backlash. Lewis stood firm for nonviolence.

The reader of this book will take away an appreciation of what Lewis and other Civil Rights leaders endured. At a time when many of our rights as Americans feel threatened, the examples of those like Lewis, who Meacham likens to the Founding Fathers, provides an example of what courage looks like. He kept his eye on justice, avoiding violence but willing to get into “good trouble.”

I have read four other books by Jon Meacham and reviewed Let There Be Light. Like His Truth is Marching On, Let There be Light is also a spiritual biography, but of Abraham Lincoln. I have also read his biographies of George H. W. Bush and Andrew Jackson. All have been exceptional.

Mary Oliver, Upstream: Selected Essays

(2016, Audible, Pushkin Industries, 2023, 4 hours and 3 minutes)

A number of years ago read some of Mary Oliver’s poetry and her book on writing poetry. This is my first foray into her essays. This collection has been finely crafted, showing Oliver’s love for nature, life, and her home in Provincetown at the eastern tip of Cape Cod. As with her poetry, Oliver provides the reader with close views of the world. Owls, foxes, herons, spiders, turtles, fish, and her beloved dogs are all captured with her words. The reader learns the poet’s blessings upon those in the past. She drew strength from writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Edgar Allen Poe, William James, Walt Whiteman, William Wordsworth. She takes us on predawn walks. We’re introduced to a carpenter who wants to be a poet. Then we learn of her desire to master woodworking. I recommend this series of essays as a reminder to take our time to enjoy what’s around us.

Amanda Held Opelt, Holy Unhappiness: God, Goodness, and the Myth of the Blessed Life

(New York: Worthy Publishing, 2023), 239 pages including notes.

The title of this book, “Holy Unhappiness,” caught my attention. After all, doesn’t God want us to be happy? Doesn’t God want us to be blessed? Drawing on the account of the fall from Genesis 3, Opelt counters the idea we’re made to be happy. The curse of humanity includes our suffering in this life. Of course, the pursuit of happiness, which Americans hold dear, isn’t found in Scripture but the Declaration of Independence. Yet such ideas have found their way into American Christianity through the various forms of the prosperity gospel. Opelt’s book directly attacks the heresy of the prosperity gospel.

The author grew up in a loving Christian middle-class family in the Bible Belt. She felt she did all the things required of her to achieve blessedness. But as she grew older, she realized many of her expectations were hollow. The idea she just had to find the right job, the right spouse and they’d have the perfect children, and life would be easy was an allusion.

The book is divided into three parts. Each looks at four places where we seek blessings followed by a chapter on the real source of blessings. The first part of the book looks at us as individuals in our work, marriage and parenthood. While there are wonderful aspects to each of these, they can also fluster our attempts to obtain a blessing. The real blessing comes in our delight of accepting what God has given us.

Part two focuses on our life in a community. While much of American Christianity is focused on individuals, Opelt points out that the gospel is to be lived out with others. In this section, she discusses calling and community along with our bodies (through which we serve and work together). The blessing we discover is humility. The third part examines our gathering as believers, along with our suffering and sanctification. The resulting blessing is hope.

Opelt encourages American Christians to avoid “one-verse-theologies” and to delve into the Scriptures. I applaud this suggestion. However, I wonder why Opelt didn’t link suffering and “holy unhappiness” with the cross. Perhaps this is because I am writing this review during Lent, or because yesterday I read nearly 100 pages of Fleming Rutledge’s, The Crucifixion. Nonetheless, there is a lot to commend in Opelt’s book. I was especially moved by what she has to say about the community, the church, and humility.

Oplet will be one of the presenters at this year’s HopeWords Writer’s Conference in Bluefield, West Virginia.

Nathaniel Philbrick, Travels with George: In Search of Washington and His Legacy

(Penguin Random House, 2021), 375 pages include notes, bibliography and index. Penguin Audio, 2021, narrated by Nathaniel Philbrick, 9 hours and 34 minutes.

This is the third book I read by Philbrick. The first two were In the Heart of the Sea: the Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex and Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution. I have enjoyed all three and have his book on the Mayflower sitting on my to-be-read pile.

I began listening to on audio, but ended up picking up a copy from the library. This allowed me to follow along and to see the illustrations. Most notably is John Trumbull’s painting of George standing in front of the hind end of Prescott, his horse. Prescott’s tail is raised. In the background sits the city of Charleston, for whom the painting was made. The artist’s joke is that the horse is relieving himself on Charleston even though I first thought Washington was lifting up the horse’s tail (as to say, go here?).

Unlike the other two books of Philbrick’s I read, this one is more personal. Philbrick and his wife Melissa along with their dog, Dora, retraces the steps of Washington in their Honda Pilot. The one time they left their car behind was to sail, like Washington, to Rhode Island. This created an exciting adventure as they were caught in a dangerous storm. Thankfully, they’d left Dora behind.

Both Philbricks are avid sailors. Early in their married life, Philbrick stayed at home and cared for the kids while working as a freelance writer. Melissa worked as an attorney. I also discovered that he grew up in Pittsburgh. However, he spent lots of time in the summer on the coast where he could sail. Sadly, Phil did not reveal if he remained loyal to Pittsburgh’s sports or if he became a traitor for the Red Sox’s and Patriots.

Blending into their personal experiences along the road, we learn much about Washington and the challenges he faced as the first President of the United States. At the time, the nation’s future was far from certain. Washington, a “Federalist,” was from the anti-federal South. Like all great men, he had his faults, especially when it came to his inconsistent views on slavery. Yet Washington was the man who brought the nation together. He strove to unite a collective group of former colonies into the United States. Philbrick notes that Washington didn’t desire the Presidency. Furthermore, Martha really didn’t relish the possibility of being the First Lady). During the time Washington made these journeys, he also worked on establishing the nation’s capital along the banks of the Potomac. This effort remained on his mind while on his last and longest of the journeys through the South.

Washington’s journeys begins as he leaves his home at Mt. Vernon for New York. There, he took the oath of office. His desire to learn more about the nation and show national unity, Washington, led to these trips.

His first journey left New York for New England, with stops in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and a brief foray into Maine. Notably, he skipped Rhode Island as it had yet to ratify the constitution. However, Maine wasn’t even being considered as a state and it didn’t become one until 1820.

Washington’s second journey was a tour of Long Island. The Island had mostly remained under British Control during the Revolution. However, a series of spy rings on the island, kept Washington informed as to the British plans. Even during this trip, Washington kept the identity of almost all the spies quiet. At this time, his concern continued to be their safety. What would happen if the nation failed and Britain regained control?

Then, in August 1790, Washington sails from New York to Rhode Island. While he shunned the colony on his New England trip, he wanted to welcome them into the union after they ratified the constitution. Washington stayed with John Brown, a Quaker who helped establish Brown University. Philbeck had attended Brown, and his family had long ties to the university. We learn Brown’s chariot provide Washington with ideas of the type of coach needed for his southern journeys. More importantly, however, to the story was the Quakers mixed relationship with slavery. While the religion shunned the practice, many of the ships bringing slaves to the Americas came from Rhode Island.

Throughout the book, Philbrick explores Washington’s own troubled relationship with slavery. It has long been noted that Washington freed his slaves upon his death, but they were only part of Mt. Vernon’s slaves. Many of the slaves belonged to his wife’s first husband and were property Washington didn’t control. Furthermore, while troubled by slavery, Washington still chased down runaway slaves and kept them in bondage. And while he was on these journeys, he traveled with enslaved menservants.

Ironically, Washington’s final tour took him through a land of which he was unfamiliar, the South. During the Revolution, Washington time was mostly spent in the northern part of the colonies. Other generals lead the fight in the South. This was area was also the least developed part of the nation. Overland travel was difficult. It was also a place that was most hostile to Washington’s ideas, especially the tax on whiskey.

For me, the Eastern leg of Washington’s Southern journey was the most familiar. Having spent my childhood in Wilmington, NC, and six years as an adult just outside of Savanah, I’ve traveled the roads which parallel Washington’s journey numerous times. Like Philbrick, I’ve read much of Archibald Rutledge’s writings. I have even published a piece on Hampton Plantation, where Washington stayed. I knew all of stories Philbrick told of Rutledge’s ancestors.

The part of the Southern journey that I was less familiar with was Washington’s westward swing which took him from Augusta, Georgia through the Piedmont of South and North Carolina. While I have been to most of the sites mentioned, I never associated them with Washington.

Washington’s travels seemed to help create the myth and numerous stories seemed to be repeated along the way. Many towns have their own version of “He’s just a man,” often exclaimed by some youngest when they met Washington. Another popular and frequent story are about the coins he gave out as gifts. Interestingly, these were British coins as America had yet to mint its own money. And then there was the stories of Washington’s beloved dog, “Greyhound.” Sadly, Philbrick discovered the story had been made up in the 19th Century.

While this book wasn’t as detailed in historical research as the other Philbrick books, I enjoyed it. Philbrick. portrait of Washington gives insight into the type of leadership our nation needs at present. Furthermore, reading this book makes me think it’s time for a road trip.