John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History (2004, Penguin Books, New York, 2018), 548 pages, some photos, index and notes.

This is an impressive book that does more than just provide a history of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Barry provides a history of medicine especially in the United States, of the science around disease’s transmission, and of how all this came to play in the pandemic that struck the world at the end of World War I. He even suggests that the disease may have shortened the war and may have led to its disaster the followed in which set the stage for the Second World War. The war ended after German’s last great offensive was unable to be continued because too many German troops were ill and unable to sustain German’s advance. In the negotiations afterwards, it appears that many (including Woodrow Wilson) may have battle with influenza (which may have played a role in his stoke). Wilson’s absence and lack of focus toward the end of the negotiations certainly hindered his ability to keep the French imposing punitive measures on Germany.

In an addition to providing background history to the medical profession and the science of disease (which sometimes became confusing to me as a layperson in this area), Barry also describe the transmission of the disease from birds to humans and other animals (especially swine). One it’s in the body, he describes our natural immune response. Interesting (and frightening) is that this strain was so dangerous in younger patients whose immune systems often overreacted and caused a faster death. He also pointed out that most of the deaths weren’t directly from the flu, but because the flu opened up pathways for other infections, especially pneumonia. (This is something that is enlightening in the current COVID-19 debate, as there are some who say that only those who died of COVID only should be counted as a COVID death. Most influenza deaths were not from the flu but from pneumonia).

No one knows for sure where the pandemic began. Although it became known as the Spanish flu, it is certain that the flu didn’t begin there. Spain was relatively late in being attacked by the flu, however since Spain wasn’t at war (unlike the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany and Italy), there was no censorship of the press in Spain, so people often associate the flu with the country reporting the flu. The other countries in war censored the information about the flu to keep information from their enemies even though all armies (and countries) were battling it at the same time.

One theory is that the flu began in Kansas, which had a similar illness in pigs. As those from the area were drafted into the army, they brought the illness into induction centers. Early on, the army was battling the flu. The army, as it began to mobilize after the United States entered the war, began to move personnel around the United States and to Europe. Interestingly, all medical personnel with the military knew the danger of illness being spread by armies (and early on sought to minimize the danger of measles). The disease also travelled in waves, starting in the spring of 1918. The peak was in the fall of 1918, but it kept moving and slightly changing. There were people who caught it more than once, although most who survived an early attack had protection against later attacks. It is also thought that the virus became less lethal in each wave.

Another reason this outbreak was so deadly is that the army sucked up the best doctors and nurses in the country, which left older and ineffective physicians treating civilian populations. The military (and others) passed the disease off as “just influenza” and wasn’t willing to stop the movement of personnel as a way to prevent the disease spread. However, late in the war, they did postpone drafts because the military was having a harder time trying to care for their own ill and were incapable of processing new recruits.

Just as in the current COVID crisis, many places in which influenza was rampant shut down gathering places, including restaurants, bars, churches, and theaters. The lack of knowledge was especially daunting (caused by censorship that kept anything that might slow the war effort down). This led to panic and in many places, people refused to help those in need out of fear of catching the disease. The deaths numbers in some places (especially parts of the world without much natural immunity to influenza viruses) were horrific. Fifty million and perhaps as many as a 100 million worldwide died at a time when the world’s population was 1/3 of what it is today.

I recommend this book, especially now, when we are dealing with another pandemic. The parallels are frightening, and this book could help clear up a lot of the misinformation that abounds today.

Jesse Cole, Find Your Yellow Tux: How to be Successful by Standing Out (Lioncrest Publishing, 2018), 303 pages, some photos.

Jesse Cole, Find Your Yellow Tux: How to be Successful by Standing Out (Lioncrest Publishing, 2018), 303 pages, some photos.

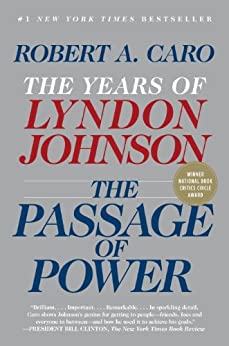

Robert A. Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power (New York: Alfred Knopf, 2012), 712 pages including notes and sources and 32 inserted pages of black and white photos.

Robert A. Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power (New York: Alfred Knopf, 2012), 712 pages including notes and sources and 32 inserted pages of black and white photos. David Lee, Mine Tailings (Boulder, UT: Five Sisters Press, 2019), 79 pages.

David Lee, Mine Tailings (Boulder, UT: Five Sisters Press, 2019), 79 pages.

James H. Cone, (Marynoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2011), 202 pages including notes and an index.

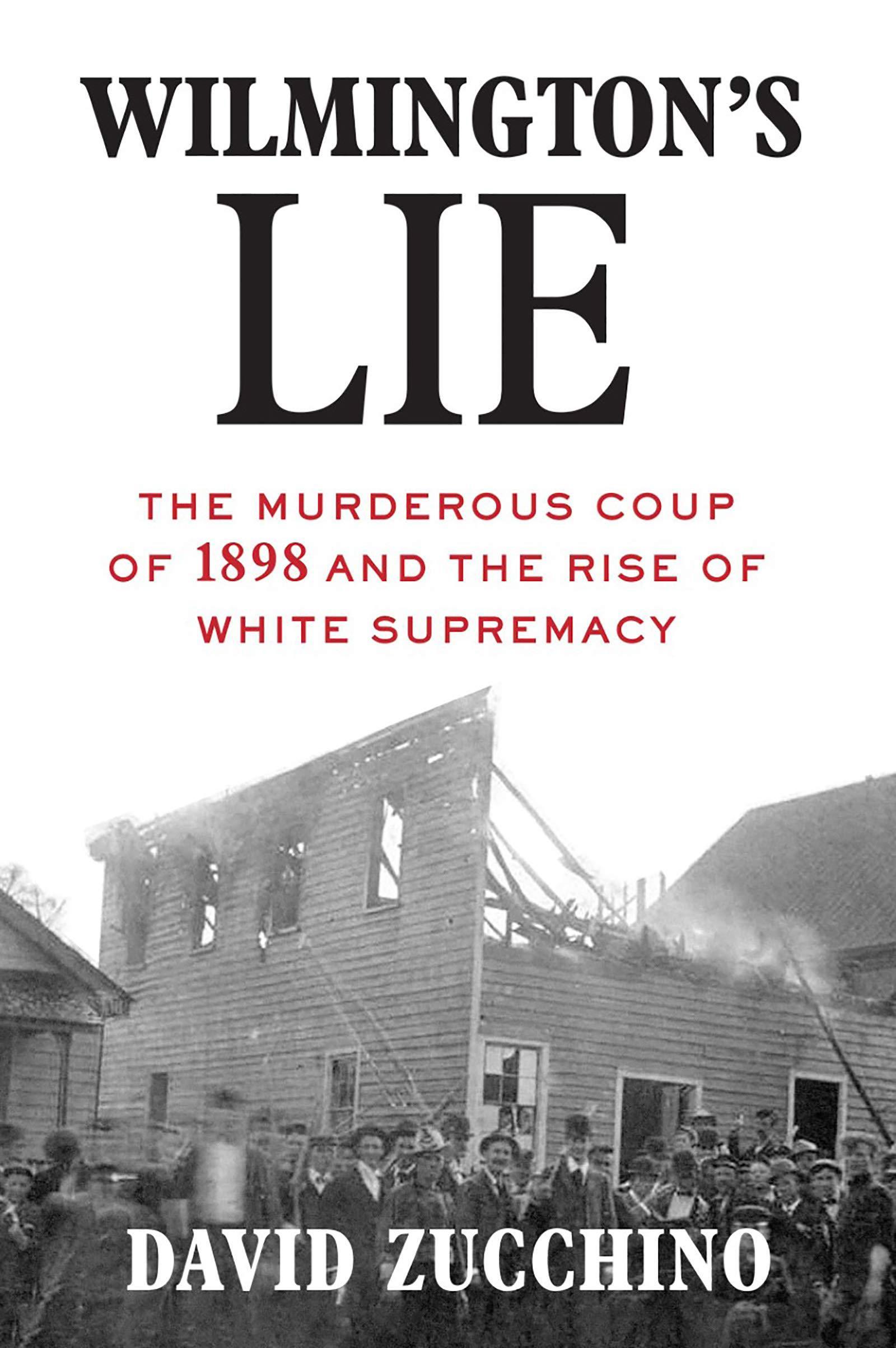

James H. Cone, (Marynoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2011), 202 pages including notes and an index. David Zucchino, Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020), 426 pages including notes, bibliography, and index along with 12 additional pages of prints.

David Zucchino, Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020), 426 pages including notes, bibliography, and index along with 12 additional pages of prints.