Joy Harjo, Conflict Resolutions for Holy Beings: Poems. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2015) 139 pages.

I picked up this book after learning that Joy Harjo has been appointed poet laureate for the United States. It’s exciting because she’s the first Native American to serve in this position. In addition to being a poet, Harjo is also a jazz musician. Her poetry blends music with longing for a home that seems evasive. In different poems, the reader is taken an “Indian school” in Oklahoma, to the hunting grounds of the Inuit people in northern Alaska, and through airports and other locals in between. She alternates between more free-form poetry to “prose poems.” Many of the poems draw the reader into the experience of modern Native Americans, who, having lost a homeland, are not sure where they belong. We also are reminded of the realities within Native communities of alcoholism and suicide. Yet, a thread of hope weaves through these poems, as we (as well as all creation) are encouraged to be blessing to others. I find her poems accessible and easy to understand. I’m sure I will reread many of them as I continue to ponder their messages. .

I picked up this book after learning that Joy Harjo has been appointed poet laureate for the United States. It’s exciting because she’s the first Native American to serve in this position. In addition to being a poet, Harjo is also a jazz musician. Her poetry blends music with longing for a home that seems evasive. In different poems, the reader is taken an “Indian school” in Oklahoma, to the hunting grounds of the Inuit people in northern Alaska, and through airports and other locals in between. She alternates between more free-form poetry to “prose poems.” Many of the poems draw the reader into the experience of modern Native Americans, who, having lost a homeland, are not sure where they belong. We also are reminded of the realities within Native communities of alcoholism and suicide. Yet, a thread of hope weaves through these poems, as we (as well as all creation) are encouraged to be blessing to others. I find her poems accessible and easy to understand. I’m sure I will reread many of them as I continue to ponder their messages. .

Archibald Rutledge, My Colonel and his Lady, (1937: Indianapolis, The Bobby’s-Merrill Company, reprinted 2017), 92 pages.

In this short book, the former poet laureate of South Carolina, Archibald Rutledge, writes a memoir of his parents. His father had been the youngest colonel in the Confederate army. His father joined the war in North Carolina (the family kept a mountain home to escape to in the summer). He was wounded three times, involved in many engagements and served as best man for General Pickett, when he married. Archibald was the youngest child of the family (for which, his father often called him Benjamin, for Jacob’s last son). He was born in 1883, nearly twenty years after his father’s military experience had ended. Rutledge was in awe of his father, whom he saw as a kind, gentle, and loving man. His father shared with him the love of all things wild-hunting and fishing and just walking in the woods. He also shared his love of the creator whom he saw revealed in nature. His mother, the colonel’s lady, was also a kind but strong woman. As her husband was often away, she had to take control as she did directing the successful efforts at fighting a fire in the great house (when water had to be drawn from the river by buckets) and shooting to scare away intruders who were looking to steal from their rice barn. She also impressed the young Rutledge with her love of books and her care of others (she often served as a medical resource in a community that often had to go without physicians).

In this short book, the former poet laureate of South Carolina, Archibald Rutledge, writes a memoir of his parents. His father had been the youngest colonel in the Confederate army. His father joined the war in North Carolina (the family kept a mountain home to escape to in the summer). He was wounded three times, involved in many engagements and served as best man for General Pickett, when he married. Archibald was the youngest child of the family (for which, his father often called him Benjamin, for Jacob’s last son). He was born in 1883, nearly twenty years after his father’s military experience had ended. Rutledge was in awe of his father, whom he saw as a kind, gentle, and loving man. His father shared with him the love of all things wild-hunting and fishing and just walking in the woods. He also shared his love of the creator whom he saw revealed in nature. His mother, the colonel’s lady, was also a kind but strong woman. As her husband was often away, she had to take control as she did directing the successful efforts at fighting a fire in the great house (when water had to be drawn from the river by buckets) and shooting to scare away intruders who were looking to steal from their rice barn. She also impressed the young Rutledge with her love of books and her care of others (she often served as a medical resource in a community that often had to go without physicians).

One interesting fact I learned about the low country was a tsunami struck South Carolina following the great earthquake in Charleston in 1886. The family was staying at their “beach home” in McCellanville, South Carolina and Archibald was only three. Suddenly the water started rushing in and his mother quickly put him and a sister on a table and went to make sure the other children were safe. The water rose several feet before rushing back out to the ocean. I knew of the earthquake and its damage, but not the coastal damage from wave action.

The Rutledge family lived on a plantation that had been in the family since the 17th Century. It survived the war (it was outside of Sherman’s march through South Carolina). Of course, by the time Archibald Rutledge was born, there was no longer slaves working the fields, but sharecroppers and those who gave a day’s work a week to “rent’ their cabins. I appreciate the way Rutledge describes his encounters with the natural world, but he does display a paternalistic view when he discusses those former slaves who lived on the plantation. This book provides a glimpse into another era and the reader should remember that its view is somewhat nostalgic and romantic. This is the third book I’ve read and reviewed by Rutledge.

Sebastian Junger, The Perfect Storm (W.W. Norton, 1997, audible 2014, 9 hours and 25 minutes.

I watched the movie, “The Perfect Storm,” many years ago, but really enjoyed the book. Junger has mastered a style used by Herman Melville. Through Melville’s novel, Moby Dick, Melville blends an exciting tale with the explanation on how the crew lived, sailed and hunted whales. Junger, in telling the story of the demise of a swordfish boat, provides enlightening detail into the method of longline fishing along with metrological details and the role the Coast Guard and other rescue groups perform when the weather turns rough. Writing about a particular weather event that occurred in 1991, he primarily focuses on the men of the fishing boat Andrea Gail. He introduces his readers to the crew and their families and the “Crow’s Nest,” a favorite bar back in Gloucester, MA, from where the boat sails. In addition to the problems faced by the Andrea Gail, which was lost at sea and never found, he speaks of some dramatic rescues that were made by the Coast Guard as they rescued three from the sailboat Satori, deal with other floundering boats such as a Japanese fishing ship, and also rescued all but one of an Air National Guard helicopter crew that ditched after a refueling attempted failed. One of the members of the crew was lost at sea. This is wonderful writing and an exciting read (or, my case, an exciting listening event). I highly recommend it.

For Hazel Brown

For Hazel Brown

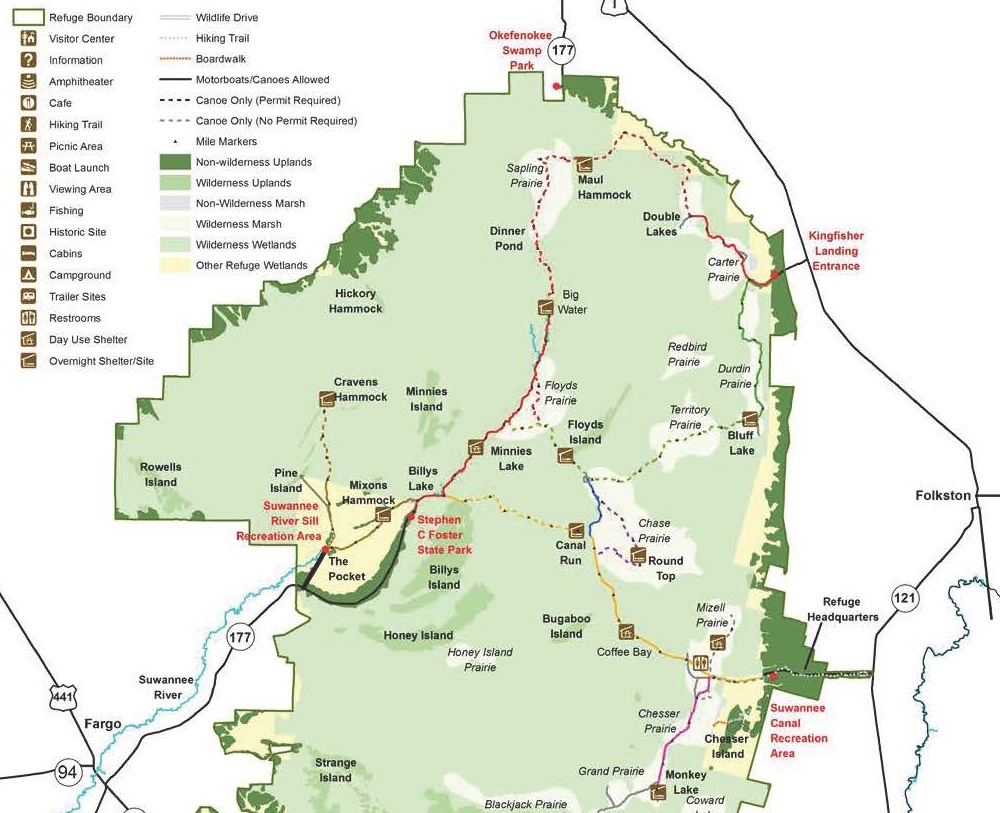

We eat lunch under the front porch during a downpour. A turkey and a fawn with spots make their way through our camp as we wait for the rain to clear. Later in the afternoon, when the storms have cleared, we move our kayaks, portaging over the quarter mile or so of the island, so that we’d be ready for the next day’s paddle. That evening, we cook over an open fire. The smoke helps deter the biting flies. We enjoy crackers and cheese, party nuts, along with some Johnny Walker Black Label. Again, I’m impressed with Gary’s beverage selection. I’m saving my cheap bourbon. Tomorrow, Gary will paddle out of the swamp while I will stay for another night.

We eat lunch under the front porch during a downpour. A turkey and a fawn with spots make their way through our camp as we wait for the rain to clear. Later in the afternoon, when the storms have cleared, we move our kayaks, portaging over the quarter mile or so of the island, so that we’d be ready for the next day’s paddle. That evening, we cook over an open fire. The smoke helps deter the biting flies. We enjoy crackers and cheese, party nuts, along with some Johnny Walker Black Label. Again, I’m impressed with Gary’s beverage selection. I’m saving my cheap bourbon. Tomorrow, Gary will paddle out of the swamp while I will stay for another night.

It’s good that we didn’t explore because after the turn-off to Double Lakes, the trail becomes more difficult. In places, lily pads and other weeds fill the channel and often seem to grab and hold on to your paddle. It’s a workout, but we keep paddling. The lily pads include the elegant blooming white lotus plants and some of the more bland yellow blooms. Along the sides of the path, where it is open, are hooded pitcher plants, purple swamp irises and pickerel weed with its purple torch-like flowers. At places, bladderworts, odd flowering plants that grow in water, are seen. Like the pitcher plants, they too are carnivorous. With so many insect eating plants, you’d think bugs wouldn’t be a problem. The abundance of these plants are an indication of the poor soil, so they have evolved to obtain nutrients from other sources. And there seems to be plenty of mosquitoes and biting flies to feed these plants, as we’ll later experience.

It’s good that we didn’t explore because after the turn-off to Double Lakes, the trail becomes more difficult. In places, lily pads and other weeds fill the channel and often seem to grab and hold on to your paddle. It’s a workout, but we keep paddling. The lily pads include the elegant blooming white lotus plants and some of the more bland yellow blooms. Along the sides of the path, where it is open, are hooded pitcher plants, purple swamp irises and pickerel weed with its purple torch-like flowers. At places, bladderworts, odd flowering plants that grow in water, are seen. Like the pitcher plants, they too are carnivorous. With so many insect eating plants, you’d think bugs wouldn’t be a problem. The abundance of these plants are an indication of the poor soil, so they have evolved to obtain nutrients from other sources. And there seems to be plenty of mosquitoes and biting flies to feed these plants, as we’ll later experience.

David Halberstam, The Fifties (1993, New York: Ballantine Books, 1994), 800 pages including index’s and notes, plus 32 pages of black and white prints.

David Halberstam, The Fifties (1993, New York: Ballantine Books, 1994), 800 pages including index’s and notes, plus 32 pages of black and white prints.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Purple Hibiscus (2003, New York: Random House/Anchor, 2004), 309 pages.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Purple Hibiscus (2003, New York: Random House/Anchor, 2004), 309 pages. Rick Bragg, The Best Cook in the World: Tales from My Momma’s Table (2018), 19 hours and 17 minutes on audible.

Rick Bragg, The Best Cook in the World: Tales from My Momma’s Table (2018), 19 hours and 17 minutes on audible. Jack Kelly, The Edge of Anarchy: the Railroad Barons, the Gilded Age, and the Greatest labor uprising in America (2019) 11 hours and 15 minutes on Audible.

Jack Kelly, The Edge of Anarchy: the Railroad Barons, the Gilded Age, and the Greatest labor uprising in America (2019) 11 hours and 15 minutes on Audible.