This is a follow-up story to the one I posted before Christmas, when I wrote about my first long distant train trip from Pittsburgh to Florida and the only train wreck I’ve experienced. Click hereto read the story. Click here to read about my visit to Pittsburgh last summer.

New Years Day 1987

Soon after the conductor checked me in and shortly after pulling out of the DC Station, I headed to the lounge car for a beer and a sandwich for dinner. In a corner booth, several obviously intoxicated guys played cards. I sat diagonally across from them, in the only open seat. Across from me, another conductor did paperwork. We exchanged greetings. He went back to his work, and I took a bite into my sandwich and looked out the window.

Darkness was upon us. But every so often the flashing red lights at gates dispelled the descending darkness as we crossed highways. Leaving DC, the tracks snaked along the Potomac. The icy winter mix we’d been experiencing all day had changed to big snowy flakes by the time we reached Harper’s Ferry. After finishing my sandwich, I purchased another beer and pulled out The Bridge Over the River Kwai. I only had a few pages left, which I read while downing my beer.

The guys in the poker table in the corner kept hollering and then one of them told a racist joke. The car attendant came over and told them they’d been inappropriate and need to return to their seats. When they asked for another beer to take with them, he refused, saying they’d had enough. The game broke up and all but one walked away. This guy became louder, shouting obscenities and racial slurs. The conductor immediately stood up in support of the car attendant, as he called for assistance on his radio.

I wondered if I was going to witness my first mobile bar fight. The three men, the drunk on one side, the conductor and attendant on the other, appeared locked in a stand-off, waiting for someone to blink. The man was told again that had better go back to his seat or he’d be removed from the train. He refused and sat back down in defiance.

I’m not sure who made the call, perhaps the other conductor who had stepped into the car and stood at the back. Everyone remained quiet, with the drunk staring at the attendant and conductor. A few minutes later the train slowed. At a lonely snow-covered road, with the flashing lights of a sheriff’s car competing with the crossing lights, the train came stopped. The engineer had parked the lounge car in the middle of the road.

The attendant opened the door, and two sheriff deputies entered. They spoke briefly to the conductor, and then to the drunk’s amazement, told him he was under arrest. He asked if he could go back to his seat but was cuffed and led out into the night. The conductor made a call from his radio, the whistle blew, and the train jerked forward. Everyone in the lounge car remained quiet, surprised by what we’d witnessed.

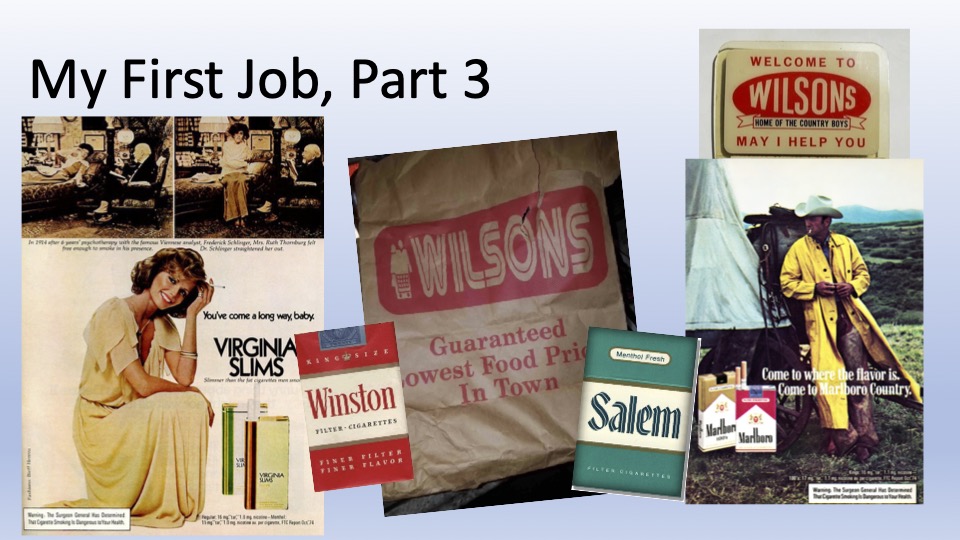

The day, cold and gray, had started early as I’d boarded the Silver Star in Southern Pines, North Carolina. I’d spent New Year’s Eve with my Grandma, barely making it till midnight. I was in bed soon after Dick Clark finished clicking off the seconds of 1986 at Times Square.

Boarding the train, I was seated in a coach that I soon learned had a malfunctioning heating unit. Everyone was cold and the attendant had given out every blanket he had. I pulled my sleeping bag from my backpack and sat down, sliding my legs into it. My eyes alternating from the barren winter landscape outside to the pages of The Bridge over the River Kwai.

In Raleigh they tried to fix the heating unit, and again in Petersburg, but in both cases, as soon as we were running, the unit kicked out. The train, filled with folks heading home for the holidays, was full. There were no available seats in the other cars. That afternoon, I napped, warm in my bag, as sleet and freezing rain pounded against the window. There wasn’t a second to pause when we reached Washington, D. C. We were late and I had to immediately board the Capitol Limited for its run toward Chicago. Winded, I was at least pleased to find a warm coach with a working heat unit.

After my light dinner and the evening entertainment, I’d returned to my seat. The train crossed over the Appalachians and began the downhill dart through coal towns nestled along the Youghiogheny. The snow piled up. When we stopped at the little hamlets, folks getting off the train would leave footprints in the powder as they head toward the station or awaiting cars. Some looked around, as if waiting for someone who wasn’t there to greet them. This was such a lonely scene, I thought. As the tracks approached Pittsburgh, running through the Monongahela Valley, I saw flames coming from the few steel mills still operating. Their red glow cutting though the darkness. A few minutes later, we pulled into Pittsburgh. As I got off, I wonder if I’ll have a ride, if Rusty has been able to make it through the snow to pick me up.

Sure enough, Rusty was waiting in the station. Pittsburgh had received nearly a foot of snow, but he was used to driving in it. The roads were vacant as we drove through town. Once we got back to the school, I dropped my bags in my apartment, pulled on my boots and headed outside. It was early in the morning, January 2nd, but I couldn’t sleep. Outside something magical happened. The dreary day had been transformed and now, at night, the snow added a cheerfulness to the air. I walked along Highland Avenue, enjoying the left-over Christmas lights that pierced the darkness. I was home.

Postscript: Two days later, my mother called to make sure I was okay. She had heard of a terrible train wreck in Maryland. I don’t know why she worried that I was on that train unless she felt that my former trip’s wreck made me unlucky on trains. The accident turned out to be the one of the worse rail accidents in Amtrak history as a set of Conrail engines ignored lights and crossed in front of the Amtrak train.