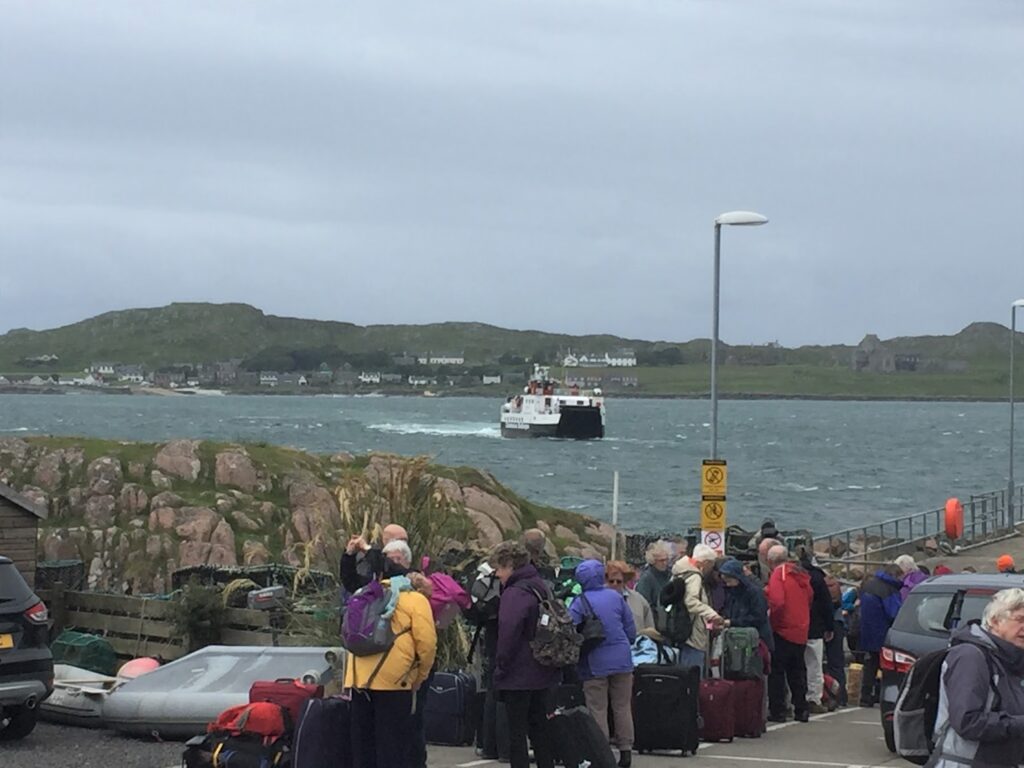

I’ve been gone for the last nine days. Last week, I attended the Theology Matters Conference at Providence Presbyterian on Hilton Head Island in South Carolina. This is their third conference and they’ve all had excellent presentations. This was no exception. Then I headed down to Skidaway Island, where I lived outside of Savannah. There I met up with some friends I used to gather with for late Friday afternoon board meetings. I also got in some sailing with other friends. Then I drove up to Wilmington, NC, to see my dad, along with one of my brothers, my sister, and some friends. While the wind kept us off the water, I did do some hiking around Carolina Beach State Park. I came home yesterday. Below, I review three books I read while away:

Douglas W. Tallamy, The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees

(Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 2021), 197 pages including references, planting guides, and index. Many photos.

The author moved to a new home in Pennsylvania in 2000. Shortly afterwards, he collected an acorn from a nearby white oak tree. Planting it in a container, it sprouted. After it grew some, he replanted on his property. After 18. years, the white oak is still young, but nearly forty feet tall. He author comes back to this tree, which serves as his laboratory for studies and his example for talking about the lives associated with oaks. This book is organized month by month as we gain insight into what’s happening to the oak as well as those whose lives depend on oaks. Such lives include not just insects and caterpillars living on the oaks, but also birds and other animals that feed such animals.

This book is a delightful read. While I have known that trees often have bumper crops of acorns and other fruit, I never knew it had a name (masting). I always assumed this phenomenon helped overwhelm animals depending on certain seeds, knowing that they couldn’t eat all of a bumper crop and some seeds will help the plant reproduce. I learned this is only one of three possible answers to the question of “masting.” Nor did I know that blue jays will often bury acorns up to a mile from the oak that produced the seed. Nor did I know that oaks provide a larger percentage of the insects needed by songbirds to survive than other trees. While I certainly knew that oaks and even more so, birch, hold their leaves sometimes through winter, I know why or that there was a name to describe this phenomenon (marcescent). Even more amazing is Dolbear’s Law, which accounts for how fast crickets chirp based on the temperature. These are just a few of the interesting facts presented by Tallamy in his book of wonder.

Tallamy warns us of overusing insecticides, which have devastating impact on wildlife (especially birds). He shows how the oak is quiet resultant, often surviving attacks by insects and even plants like mistletoe that live in its limbs. Because of this book, I’m going to find some white oak acorns and plant them on my property! Of course, don’t expect this book to teach you how to tell the difference between a white, red, or black oak. This is not a guidebook, but a book that describes how a specific tree can benefit our world.

Thorpe Moeckel, Down by the Eno, Down by the Haw: A Wonder Almanac

(Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2019), 127 pages.

I picked up this book because when I was younger, I felt the call of the Haw River and wanted to spend as much time as possible running its rapids. I’d never paddled the Eno, but I knew of it. I was expecting to learn more about these two streams. Reading the book, I was shocked to learn that wasn’t what the book is about. Instead, the author who is also a poet, spent a year collecting these thoughts while living in the North Carolina piedmont. He’s drawn into the woods. While he mentions rivers, he doesn’t identify which one. Other times, he’s visiting a pond instead of a river or describes walking in the woods. His focus is to describe in detail what is going own around him. It must have been a year with many hurricanes striking the coast for Moeckel describes their aftermath after they pour out their water over the piedmont and mountains.

Like The Nature of Oaks, Moeckel divides his thoughts by months. In each month, he makes multiple trips into the woods. He’s observant and his writing reads like a prose poem. It took me a few months to really get into his writing. By the end, I was sad there were no more months. To read about my first experience with the Haw and another book review of the river, click here.

Rick Bragg, A Speckled Beauty: A Dog and His People

(2021, Audible), 6 hours and 22 minutes.

The thing about dog stories which have haunted me since I watch Old Yeller as a kid is that in the end, the dog dies. And I have shed more than my share of tears over the death of dogs, both those I’ve known in life and those I’ve read about. The good thing about this book is that Speck doesn’t die. He lives on with us, still chasing cars and animals and rolling in stinky dead stuff. As Bragg claims, his dog isn’t a “good boy,” but he still uses that term. When Bragg is away from home, his mother, or his brother (who lives next door) are likely to throw Speck in jail (the outdoor pen). But Bragg has a soft heart from this stray dog that showed up one day at his house. The dog was missing an eye and beaten up, having obviously been in a few fights. Bragg cleans him up and as he recovers, takes him to the vet. It was just what a man, who had a host of health issue, needed. He nurses the dog back to health and in a mysterious way, the dog helps him overcome heart and kidney failure, cancer, and other ailments of a man beginning his sixth decade.

I listened to this book. The author reads the story. His slow voice tells the story in a way that I might have been out on the back porch listening. Of course, I wasn’t. I was in a car on a six-hour drive to a conference on Hilton Head Island. While this book might be classified as a memoir of him and his family, he doesn’t focus on himself. Furthermore, Bragg’s humor is often self-effacing. He says he’s living in his mother’s basement (but if I remember correctly, in one of his other books he admits to buying his mother a house and land). And once COVID hits, the dog becomes a cherished companion.

Bragg will have you laughing and crying, sometimes in the same paragraph. This is how storytelling should be done.

I highly recommend this and many other books by Rick Bragg. See my review of another of his books, The Best Cook in the World: Tales from My Momma’s Table. My favorite book by Bragg is Ava’s Man.