Jeff Garrison

Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church

1 Timothy 6:17-19

November 17, 2019

Last week scripture from Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount was used to explore how we might “look in” on the role money plays in our lives. Because money and possessions have a power that can lead us astray, we must be careful. Today, I’m using a passage from 1st Timothy that has almost the identical message, but now I want us to look out instead of in. How does our use of money impact our community and others? We need to ask ourselves what good comes from where we spend and give our money? What kind of vision do we have for the church, our community, and world and how might we support such a vision? Read 1 Timothy 6:17-19.

###

A group of us watched “It’s a Wonderful Life” this week. The turning point of the movie has George Bailey moan that it would be better if he had never been born. Clarence, the angel sent to save him from despair, then provides a glimpse of what his community would be like without him. It goes back to when he saved his brother’s life when he was ten. In the movie, the adult George is a bit envious of his brother who became a hero in the Pacific War by shooting down kamatzes aimed at a troop ship. If he had not saved his brother, his brother would not have been there to save the ship and it would have sunk with 2000 men aboard. He also learns of the good the Bailey’s Savings and Loan has done in allowing people to own homes. In this vision, he sees the families he’d help live in terrible conditions. In fact, the town isn’t the quaint “Bedford Falls” but a raucous “Pottersville,” named for the owner of the bank. The only escape from the drudgery of the town without George appears to be sex and alcohol.

George Bailey had no idea he’d touched so many lives. Sometimes the “little things” we do are hard to see and don’t reach fruition until years later. But if we have our priorities right, we can plant such seeds that have the potential to make a difference in the world. That’s the implication from our passage from the Letter to Timothy. Let’s take this text apart and consider what we’re being told.

George Bailey had no idea he’d touched so many lives. Sometimes the “little things” we do are hard to see and don’t reach fruition until years later. But if we have our priorities right, we can plant such seeds that have the potential to make a difference in the world. That’s the implication from our passage from the Letter to Timothy. Let’s take this text apart and consider what we’re being told.

Paul speaks of those who are rich in this present age or, as another translation has it, those who are rich at this time.[1] By speaking of the present, Paul implies that those who are rich might not always be that way. Wealth comes with uncertainty. A market collapse could wipe us out. And, as we saw last week, nice things can go bad. They can rust or be eaten by moths or stolen by thieves.[2] The riches of our world are transitory. But Paul isn’t just talking about how riches can be lost or lose value in the present.

He suggests that the present won’t last forever. In God’s economy, gold and silver have little value. As Jesus says, we need to remember to store our treasures in heaven.[3]

He suggests that the present won’t last forever. In God’s economy, gold and silver have little value. As Jesus says, we need to remember to store our treasures in heaven.[3]

Paul, like Jesus, doesn’t condemn riches in and of themselves. Instead, he points out the dangers or the temptations that come with wealth. Those who are rich must be on guard for two temptations. John Calvin called them “pride and deceitful hope.”[4] The two go together, for pride comes from the hope we place in things which will ultimately fail.

Paul, like Jesus, doesn’t condemn riches in and of themselves. Instead, he points out the dangers or the temptations that come with wealth. Those who are rich must be on guard for two temptations. John Calvin called them “pride and deceitful hope.”[4] The two go together, for pride comes from the hope we place in things which will ultimately fail.

Let’s explore these two items deeper: Riches can tempt us to act haughty. In other words, we are tempted to have a big ego, or to think more of ourselves than we should. The extreme example of this type of behavior in the movie “It’s a Wonderful Life” is Mr. Potter. He’s a Scrooge-like character that doesn’t experience the joyous conversion of Dicken’s Scrooge. Riches can be a barrier from the humility that’s needed in order to properly see ourselves in God’s kingdom. Augustine, in a sermon during the 4th Century, reflected on this passage saying riches isn’t the problem, it’s the disease which some get from riches which is pride.[5] The vaccine to this disease is generosity.

Let’s explore these two items deeper: Riches can tempt us to act haughty. In other words, we are tempted to have a big ego, or to think more of ourselves than we should. The extreme example of this type of behavior in the movie “It’s a Wonderful Life” is Mr. Potter. He’s a Scrooge-like character that doesn’t experience the joyous conversion of Dicken’s Scrooge. Riches can be a barrier from the humility that’s needed in order to properly see ourselves in God’s kingdom. Augustine, in a sermon during the 4th Century, reflected on this passage saying riches isn’t the problem, it’s the disease which some get from riches which is pride.[5] The vaccine to this disease is generosity.

The second temptation of riches is that we place our trust, not in God, but in our wealth. Paul reminds us, as Jesus did last week, riches are uncertain. All the wealth in the world can’t reverse certain diseases or stop a speeding bus or prevent a plane crash in bad weather, or whatever demise might befall us. Sooner or later, life will end. We must not place our trust in wealth, but in God, who provides us with the ability to create wealth in this life. God wants what is best for us, so we trust God as we move forward into the next life.

But, while we are here, in this life, we are to use our riches in ways that are pleasing to God. Instead of just enjoying our blessings by ourselves, Paul encourages Timothy to teach others to be rich in their generosity. We are to be people who do good works and who are ready to share with others. A generous life is a well-lived life. Back to the movie, “It’s a Wonderful Life,” George Bailey lives such a life as he has helped many people, and in the end when he needs help, people respond. George, who minutes earlier was ready to commit suicide, finds that he is rich beyond measure. Maybe not monetarily rich, but rich in a way that helps him to enjoy a wonder full life.

In this week’s e-news that I sent out, I linked to an article about a small Lutheran Church in Minnesota. They were down to 20 members and had enough money to carry them for 18 months when a new pastor arrived. He told them his first Sunday, “You’re dead.” Then he asked, “Now what you are going to do?” The members of the church decided if they were to die, they’d do it well, so they began to seek ways to love and care for those around them. They made no demands on those they helped. They offered to do whatever they could to help people in their neighborhood. At first, they only had a few offers. But they kept on and as they continued, they picked up volunteers. Many of these people were not religious, but they liked the idea of church being supportive of the community.[6] And while this church isn’t out of the woods yet, it has grown and is holding its own.

In this week’s e-news that I sent out, I linked to an article about a small Lutheran Church in Minnesota. They were down to 20 members and had enough money to carry them for 18 months when a new pastor arrived. He told them his first Sunday, “You’re dead.” Then he asked, “Now what you are going to do?” The members of the church decided if they were to die, they’d do it well, so they began to seek ways to love and care for those around them. They made no demands on those they helped. They offered to do whatever they could to help people in their neighborhood. At first, they only had a few offers. But they kept on and as they continued, they picked up volunteers. Many of these people were not religious, but they liked the idea of church being supportive of the community.[6] And while this church isn’t out of the woods yet, it has grown and is holding its own.

When we look beyond ourselves, we realize there are three things we can do with money.[7] We can spend it, we can save it, and we can give it away. Neither Paul nor Jesus condemned anyone for spending money on that which was needed or even on the finer things in life. God wants us to enjoy life. We’re not called to beat up on ourselves for enjoying life. Instead, we’re told in Ecclesiastes to enjoy ourselves and to take delight in that for which we’ve toiled.[8] As long as what we’re doing is wholesome, we should enjoy that which we receive from our spending and not feel guilty.

When we look beyond ourselves, we realize there are three things we can do with money.[7] We can spend it, we can save it, and we can give it away. Neither Paul nor Jesus condemned anyone for spending money on that which was needed or even on the finer things in life. God wants us to enjoy life. We’re not called to beat up on ourselves for enjoying life. Instead, we’re told in Ecclesiastes to enjoy ourselves and to take delight in that for which we’ve toiled.[8] As long as what we’re doing is wholesome, we should enjoy that which we receive from our spending and not feel guilty.

A second thing we can do with money is to save it. This, too, in and of itself, isn’t bad. We’re told in Proverbs that the wise save while the fool devours.[9] But we must remember the limitations of our nest-eggs. Our savings might make tomorrow or the next decade or our retirement easier, but it doesn’t have the ability to add a single day to our lives. So, while we should save, we shouldn’t worship that which we have saved. Our salvation is in Christ, not in our portfolios.

And finally, we can give it away. Again, over and over in Scripture we’re told how it is more blessed to give than receive and how sharing what we have with others is pleasing to God.[10] If for no other reason, we give because God has given to us.[11] Giving allows that image of God that’s in us shine as we strive to live in a manner that is more god-like.

Spending, saving, and giving. All are good, if done for the right reasons.

When we look out from ourselves, we should consider how we might make a difference with our money. Whether we can give large amounts or only a small amount, we need to see our giving as an investment in God’s kingdom. But we don’t do it only if we know we can make a difference, we do it because we know that our efforts will be joined with the giving of others and then that will be blessed by God’s Spirit. Giving is an act of faith. It’s like the message we heard from Dean Smith a few weeks ago, about how that annoying jingle of change in our pockets can be saved and when we add them with change from other pockets, we soon have enough to make a difference in the lives of the hungry. When the community comes together like this, we can make a difference in the world.

When we look out from ourselves, we should consider how we might make a difference with our money. Whether we can give large amounts or only a small amount, we need to see our giving as an investment in God’s kingdom. But we don’t do it only if we know we can make a difference, we do it because we know that our efforts will be joined with the giving of others and then that will be blessed by God’s Spirit. Giving is an act of faith. It’s like the message we heard from Dean Smith a few weeks ago, about how that annoying jingle of change in our pockets can be saved and when we add them with change from other pockets, we soon have enough to make a difference in the lives of the hungry. When the community comes together like this, we can make a difference in the world.

Next week is Consecration Sunday. We are asking for you to make an estimate of giving for 2020, to help the church do its budgeting. As you prepare yourself to make this estimate, I ask you to pray throughout the week for God to give you a vision. You can add this prayer to the prayer that you we’ve been asking you to make on behalf of the church. Ask God how you can make a difference in the world? Let us pray:

Next week is Consecration Sunday. We are asking for you to make an estimate of giving for 2020, to help the church do its budgeting. As you prepare yourself to make this estimate, I ask you to pray throughout the week for God to give you a vision. You can add this prayer to the prayer that you we’ve been asking you to make on behalf of the church. Ask God how you can make a difference in the world? Let us pray:

Almighty God, give us a vision of how we might partner with you, and with our brothers and sisters, to make a difference in the world. Amen.

©2019

[1] Contemporary English Bible translation

[2] Matthew 6:19.

[3] Matthew 6:20.

[4] John Calvin, Commentary on 1st Timothy, https://biblehub.com/commentaries/calvin/1_timothy/6.htm

[5] Augustine, Sermon 36.2 as quoted in the Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture: New Testament IX (Downers’ Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2000), 224.

[6] http://www.citypages.com/news/peace-lutheran-staved-off-death-by-taking-love-thy-neighbor-to-a-radical-extreme/563648921

[7] This idea comes from Maggie Kulyk with Liz McGeachy, Integrating Money and Meaning: Practivs for a Heart-Centered Life (chicorywealth.com, 2019). The authors spoke of four things you can do with money, adding “earning” to my list.

[8] Ecclesiastes 3:12-13.

[9] Proverbs 21:20

[10] Acts 20:35 and Hebrews 13:16

[11] Matthew 10:8

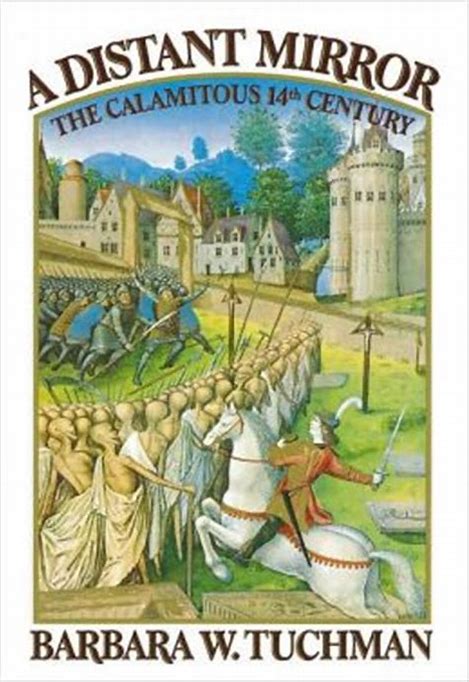

Barbara Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century (New York: Knopf, 1978), 720 pages including notes and index. Some plates of photos and artwork.

Barbara Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century (New York: Knopf, 1978), 720 pages including notes and index. Some plates of photos and artwork. Edward Dolnick, A Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society and the Birth of the Modern World, 2012 (Audible 10 hours and 4 minutes).

Edward Dolnick, A Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society and the Birth of the Modern World, 2012 (Audible 10 hours and 4 minutes). John H. Leith, Assembly at Westminster: Reformed Theology in the Making (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1973), 127 pages.

John H. Leith, Assembly at Westminster: Reformed Theology in the Making (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1973), 127 pages.

This passage is about us looking deeply and getting our priorities right. There are three connected proverbial thoughts here, which Jesus uses to encourage his listeners to evaluate their lives and to see where they are placing their trust. First, we’re not to trust worldly treasures for they have a way of disappearing. A fine wardrobe can be destroyed by moths, objects crafted out of metal can rust, and what’s to stop someone from stealing them when we’re not looking. Notice, however, Jesus doesn’t say that having nice things is bad. He just says we can’t trust them to always be there and that the problem with such niceties is that when we place too much trust in them, we risk not trusting God. Ultimately, our treasurers are going to fail us.

This passage is about us looking deeply and getting our priorities right. There are three connected proverbial thoughts here, which Jesus uses to encourage his listeners to evaluate their lives and to see where they are placing their trust. First, we’re not to trust worldly treasures for they have a way of disappearing. A fine wardrobe can be destroyed by moths, objects crafted out of metal can rust, and what’s to stop someone from stealing them when we’re not looking. Notice, however, Jesus doesn’t say that having nice things is bad. He just says we can’t trust them to always be there and that the problem with such niceties is that when we place too much trust in them, we risk not trusting God. Ultimately, our treasurers are going to fail us. The second proverbial through is about a “healthy eye.” My father just had cataract surgery this week and was telling me on Friday about how bright the colors are now that his eye is healthier. But Jesus isn’t making a pitch for eye surgery. Jesus listeners would have known right away what he was talking about when he mentioned an unhealthy or evil eye. They understood that an evil eye referred to an envious, grudging or miserly spirit, while a good eye connotes a generous and compassionate attitude toward life. One of my professors from seminary, in his commentary on Matthew, says it’s as if Jesus’ says: “Just as a blind person’s life is darkened because of an eye malfunction, so the miser’s life is darkened by his failure to deal generously with others.”

The second proverbial through is about a “healthy eye.” My father just had cataract surgery this week and was telling me on Friday about how bright the colors are now that his eye is healthier. But Jesus isn’t making a pitch for eye surgery. Jesus listeners would have known right away what he was talking about when he mentioned an unhealthy or evil eye. They understood that an evil eye referred to an envious, grudging or miserly spirit, while a good eye connotes a generous and compassionate attitude toward life. One of my professors from seminary, in his commentary on Matthew, says it’s as if Jesus’ says: “Just as a blind person’s life is darkened because of an eye malfunction, so the miser’s life is darkened by his failure to deal generously with others.” The next statement by Jesus concerns serving two masters. A slave would be run ragged if he had to answer to two masters. Likewise, if we try to serve both God and money, we find ourselves with two masters and the latter, money, makes a harsh master. There can never be enough. We need to place our priorities in order. We need to stick with God.

The next statement by Jesus concerns serving two masters. A slave would be run ragged if he had to answer to two masters. Likewise, if we try to serve both God and money, we find ourselves with two masters and the latter, money, makes a harsh master. There can never be enough. We need to place our priorities in order. We need to stick with God. It sounds too simple. “Store up your treasures in heaven; don’t worry about things here on earth.” Easier said than done, right? We all worry about having enough for tomorrow—and the day and the year and the decade that follows. We must admit that our prayers for daily bread seem unnecessary when we have a pantry full of food. When we have too much, it’s hard to depend upon God.

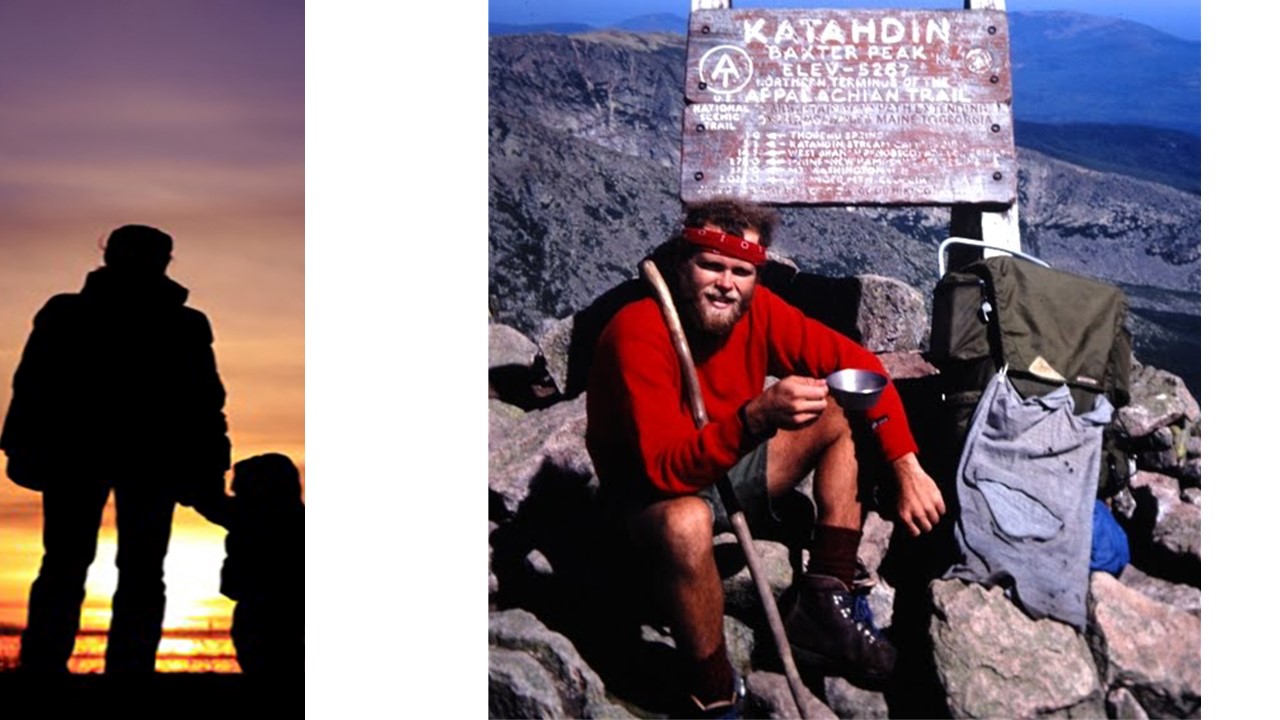

It sounds too simple. “Store up your treasures in heaven; don’t worry about things here on earth.” Easier said than done, right? We all worry about having enough for tomorrow—and the day and the year and the decade that follows. We must admit that our prayers for daily bread seem unnecessary when we have a pantry full of food. When we have too much, it’s hard to depend upon God. How might we learn not to store up our treasures here on earth? First, “Enjoy things, but don’t cherish them.” God created this world good and wants us to enjoy life and the blessings provided, but God gets angry when we see such blessings as being ours or being worthy of our worship. Second, “Share things joyfully, not reluctantly.” If it bugs you to share something you have with someone who needs it, you should then know that item has gotten a hold on you. It’s an earthly treasure, an idol. Finally, “Think as a pilgrim, not a settler.” “The world is not my home, I’m just passin’ thru,” the old gospel song goes.

How might we learn not to store up our treasures here on earth? First, “Enjoy things, but don’t cherish them.” God created this world good and wants us to enjoy life and the blessings provided, but God gets angry when we see such blessings as being ours or being worthy of our worship. Second, “Share things joyfully, not reluctantly.” If it bugs you to share something you have with someone who needs it, you should then know that item has gotten a hold on you. It’s an earthly treasure, an idol. Finally, “Think as a pilgrim, not a settler.” “The world is not my home, I’m just passin’ thru,” the old gospel song goes. Look inside yourself and use these thoughts to evaluate what you have: Enjoy, Share, and think like a pilgrim. A pilgrim is like a backpacker. Remember, you don’t want your pack to weigh you down. Amen.

Look inside yourself and use these thoughts to evaluate what you have: Enjoy, Share, and think like a pilgrim. A pilgrim is like a backpacker. Remember, you don’t want your pack to weigh you down. Amen. Not Guilty by

Not Guilty by

The characters in “It’s a Wonderful Life” provide us with archetypes for the many different ways we relate to life and we handle money. The book that goes with this series, Integrating Money and Meaning, uses these archetypes to explore our spiritual relationship with money.

The characters in “It’s a Wonderful Life” provide us with archetypes for the many different ways we relate to life and we handle money. The book that goes with this series, Integrating Money and Meaning, uses these archetypes to explore our spiritual relationship with money.

At our first forum on civility, Dr. Robert Pawlicki told of an incident when he was a psychiatrist and professor at a Medical School. A patient had gotten into an argument with a resident and he was called in by a nurse who was concerned the confrontation might become physical. Stepping between the two, he said to the patient, “You’re really angry, aren’t you?” By giving a name to what was happening and the emotions the patient showed, he opened a channel that helped the patient calm down. The situation de-escalated. This is good advice. Sometimes we need to go to the heart of the matter and, without increasing the confrontation, name the issue. But this is not what the Pharisees and the Herodians do in our morning text.

At our first forum on civility, Dr. Robert Pawlicki told of an incident when he was a psychiatrist and professor at a Medical School. A patient had gotten into an argument with a resident and he was called in by a nurse who was concerned the confrontation might become physical. Stepping between the two, he said to the patient, “You’re really angry, aren’t you?” By giving a name to what was happening and the emotions the patient showed, he opened a channel that helped the patient calm down. The situation de-escalated. This is good advice. Sometimes we need to go to the heart of the matter and, without increasing the confrontation, name the issue. But this is not what the Pharisees and the Herodians do in our morning text. It’s hard to understand this passage without explanation. The Pharisees are plotting to entrap Jesus, we’re told. How does Jesus know this? We could say that because he’s God, but that explanation doesn’t uphold the human side of Jesus. Instead, I think Jesus knew something was up when he saw the Pharisees walking hand to hand with the supporters of Herod.

It’s hard to understand this passage without explanation. The Pharisees are plotting to entrap Jesus, we’re told. How does Jesus know this? We could say that because he’s God, but that explanation doesn’t uphold the human side of Jesus. Instead, I think Jesus knew something was up when he saw the Pharisees walking hand to hand with the supporters of Herod. Jesus asks to see a coin. He has to be careful here. He doesn’t want the Pharisee’s to charge him with toting around an engraved image of the emperor. So Jesus has them to look at a coin they are carrying, and he asks them whose picture is on it…. They reply, “Caesar’s.” Jesus then tells them to give Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to give God what is God’s. The little band of tempters are astonished. Amazed and not knowing what to say, they leave…

Jesus asks to see a coin. He has to be careful here. He doesn’t want the Pharisee’s to charge him with toting around an engraved image of the emperor. So Jesus has them to look at a coin they are carrying, and he asks them whose picture is on it…. They reply, “Caesar’s.” Jesus then tells them to give Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to give God what is God’s. The little band of tempters are astonished. Amazed and not knowing what to say, they leave… The coin had an image on it, Caesar, therefore give it to him. But remember, we’re created by God, in the image of God. The coin belongs to Caesar, it has his image; our lives belong to God, they contain God’s image. Caesar may have a lien on our possessions, but God has a lien on our total being. God is calling us to dedicate our lives to himself. God, in Jesus Christ, is like those old recruiting posters found the post office, with Uncle Sam saying, “I want you.” And you, and you, and you (point at myself last).

The coin had an image on it, Caesar, therefore give it to him. But remember, we’re created by God, in the image of God. The coin belongs to Caesar, it has his image; our lives belong to God, they contain God’s image. Caesar may have a lien on our possessions, but God has a lien on our total being. God is calling us to dedicate our lives to himself. God, in Jesus Christ, is like those old recruiting posters found the post office, with Uncle Sam saying, “I want you.” And you, and you, and you (point at myself last). What Jesus does here is demonstrate the delicate balance that exists in our use of money. Money is necessary. It’s what we trade for the necessities of life. But, as is taught in the book Integrating Money and Meaning, we need to understand the power of money. If we don’t understand its lure in our own lives, it can bring out the worst in us. There’s a shadow side to money that’s pointed out in scripture. “The love of money is the root of evil,” we read in the First Letter to Timothy.

What Jesus does here is demonstrate the delicate balance that exists in our use of money. Money is necessary. It’s what we trade for the necessities of life. But, as is taught in the book Integrating Money and Meaning, we need to understand the power of money. If we don’t understand its lure in our own lives, it can bring out the worst in us. There’s a shadow side to money that’s pointed out in scripture. “The love of money is the root of evil,” we read in the First Letter to Timothy. Over my next four Sunday’s (we will skip next week with a guest preacher), we’ll look at how we spiritually relate to money. How do we balance things like paying taxes, buying what we need, and giving to God through the church? How much control does money have in our lives? What would we do if we experienced a windfall of money? Or what would you we do if suddenly your money was of no value? These are questions we should all be wrestling with as we come to understand, as Jesus taught, that money isn’t anything to fear. We’re not to fear money, but we’re warned that it contains power. If not understood, money can overtake our lives and become a dreadful master. Look back in your lives and ponder this question, “How do you spiritually relate to money?” “What kind of power does it play in your lives?”

Over my next four Sunday’s (we will skip next week with a guest preacher), we’ll look at how we spiritually relate to money. How do we balance things like paying taxes, buying what we need, and giving to God through the church? How much control does money have in our lives? What would we do if we experienced a windfall of money? Or what would you we do if suddenly your money was of no value? These are questions we should all be wrestling with as we come to understand, as Jesus taught, that money isn’t anything to fear. We’re not to fear money, but we’re warned that it contains power. If not understood, money can overtake our lives and become a dreadful master. Look back in your lives and ponder this question, “How do you spiritually relate to money?” “What kind of power does it play in your lives?”

Beverly Willett, Disassembly Required: A Memoir of Midlife Resurrection (New York: Post Hill Press, 2019), 269 pages.

Beverly Willett, Disassembly Required: A Memoir of Midlife Resurrection (New York: Post Hill Press, 2019), 269 pages.

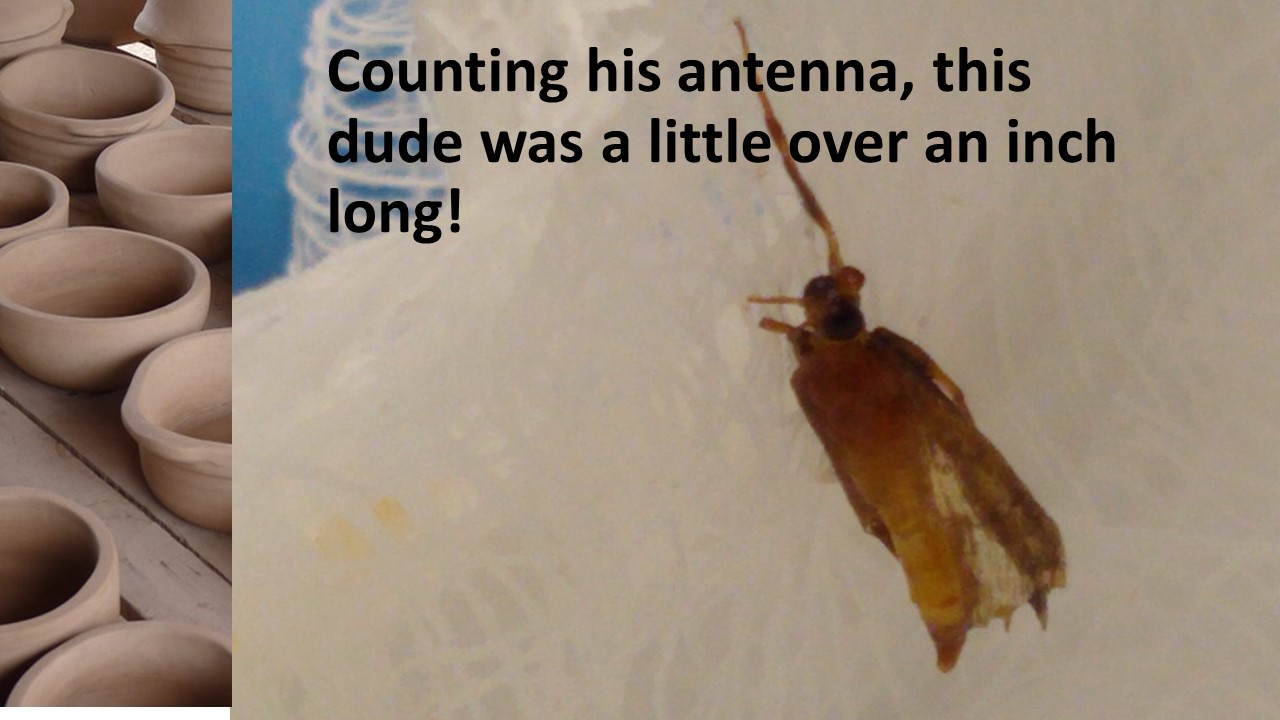

I’d ridden my bicycle down to the marina to meet with some friends late Friday. It was after dark when I left. With a rather bright LED light on my handlebars, I wasn’t worried. But about halfway home something flew into my right ear. The bug dug down deep and as it fluttered its wings. I stopped. I’d always thought the saying, “a bug in your ear,” was a metaphor. Now I was shaking my head and pounding it, in an attempt to free the bug. I was going insane. I rode on home and about every 15 seconds the insect would have saved enough energy to flutter again for a few seconds. Coming into the house, I called out that I needed help. Donna, after checking with the Mayo Clinic website, warmed up some oil and poured it into my ear. It was supposed to flush the bug out, but it never came out. Eventually the bug stopped fluttering. I assumed it drowned. Yesterday morning (which is why I wasn’t in Bible Study), I went to urgent care. They were able to remove the bug. It was a big bug and counting its antenna was over an inch long. That may not sound big until you consider the size of your ear canal.

I’d ridden my bicycle down to the marina to meet with some friends late Friday. It was after dark when I left. With a rather bright LED light on my handlebars, I wasn’t worried. But about halfway home something flew into my right ear. The bug dug down deep and as it fluttered its wings. I stopped. I’d always thought the saying, “a bug in your ear,” was a metaphor. Now I was shaking my head and pounding it, in an attempt to free the bug. I was going insane. I rode on home and about every 15 seconds the insect would have saved enough energy to flutter again for a few seconds. Coming into the house, I called out that I needed help. Donna, after checking with the Mayo Clinic website, warmed up some oil and poured it into my ear. It was supposed to flush the bug out, but it never came out. Eventually the bug stopped fluttering. I assumed it drowned. Yesterday morning (which is why I wasn’t in Bible Study), I went to urgent care. They were able to remove the bug. It was a big bug and counting its antenna was over an inch long. That may not sound big until you consider the size of your ear canal.

Professor James Cone, writing about the African American musical tradition, said that spirituals do not deny history. They don’t deny that there’s a lot wrong in our world. Instead, spirituals see history leading toward divine fulfillment.

Professor James Cone, writing about the African American musical tradition, said that spirituals do not deny history. They don’t deny that there’s a lot wrong in our world. Instead, spirituals see history leading toward divine fulfillment.

Let’s imagine ourselves in the 6th Century before the Common Era and join Jeremiah. Having left the city, the prophet walks alone, across what should be a grain field. With each step he kicks up dust. The immature stalks of grain, long dried under the desert sun, crunch under his feet. This should be the time of the harvest, but there are no men out swinging sickles nor women gathering sheaves. The grapes and the figs and the olives area also shrivel on the vine. The harvest has failed. There’s going to be hunger. And with Nebuchadnezzar’s army on the loose, there won’t be a chance to trade for food. Jeremiah’s heart is heavy. As he looks back toward the walls of the city, he cries. He images the bloated bellies of the young and the riots when there is no more bread in the market.

Let’s imagine ourselves in the 6th Century before the Common Era and join Jeremiah. Having left the city, the prophet walks alone, across what should be a grain field. With each step he kicks up dust. The immature stalks of grain, long dried under the desert sun, crunch under his feet. This should be the time of the harvest, but there are no men out swinging sickles nor women gathering sheaves. The grapes and the figs and the olives area also shrivel on the vine. The harvest has failed. There’s going to be hunger. And with Nebuchadnezzar’s army on the loose, there won’t be a chance to trade for food. Jeremiah’s heart is heavy. As he looks back toward the walls of the city, he cries. He images the bloated bellies of the young and the riots when there is no more bread in the market. “We are not saved.” What painful words. It’s tough being a prophet, bearing the burdens of a people. Yet, as he cries, he hears something. A voice? Can it be God’s voice? “I’m disappointed. Why have they provoked me to anger with their images and foreign idols?” Yes, it’s God, speaking judgment on the Hebrew people.

“We are not saved.” What painful words. It’s tough being a prophet, bearing the burdens of a people. Yet, as he cries, he hears something. A voice? Can it be God’s voice? “I’m disappointed. Why have they provoked me to anger with their images and foreign idols?” Yes, it’s God, speaking judgment on the Hebrew people.

Jesus told those in the synagogue in Nazareth that a prophet is never accepted in his hometown.

Jesus told those in the synagogue in Nazareth that a prophet is never accepted in his hometown. While Jeremiah was considered a traitor in his life, looking back we cannot help but to see that he was a true patriot. God’s people are not called to be loyal to a king or even to a nation. Our first loyalty always belongs to God and when we fail to put God first, we risk hardship, judgment, and perhaps even defeat. Do we have the faith and the perseverance of Jeremiah? Are their Jeremiahs in our society today? If so, do we listen? Or do we tune him or her out, or worse, mock and abuse?

While Jeremiah was considered a traitor in his life, looking back we cannot help but to see that he was a true patriot. God’s people are not called to be loyal to a king or even to a nation. Our first loyalty always belongs to God and when we fail to put God first, we risk hardship, judgment, and perhaps even defeat. Do we have the faith and the perseverance of Jeremiah? Are their Jeremiahs in our society today? If so, do we listen? Or do we tune him or her out, or worse, mock and abuse? You know, on the 22nd, we’re going to have our first community forum to discuss civility. If we want to build a better society, which is one of the goals of the church as we are to be a part of building God’s kingdom, we must listen to others. I hope you plan to attend and to tell others about the forum. Go to our church’s Facebook page and like the event and share it with others on your page. We have got to get our community and our nation on a new direction. We need to be about listening to all voices, even the voice of a Jeremiah, crying a fountain of tears. Only by listening to others who challenge us, like Jeremiah challenged Jerusalem, will we be able to build a better society.

You know, on the 22nd, we’re going to have our first community forum to discuss civility. If we want to build a better society, which is one of the goals of the church as we are to be a part of building God’s kingdom, we must listen to others. I hope you plan to attend and to tell others about the forum. Go to our church’s Facebook page and like the event and share it with others on your page. We have got to get our community and our nation on a new direction. We need to be about listening to all voices, even the voice of a Jeremiah, crying a fountain of tears. Only by listening to others who challenge us, like Jeremiah challenged Jerusalem, will we be able to build a better society. Let’s go back to that day, some 2500 years ago, and join Jeremiah once more… The heat of the day is over when Jeremiah starts back toward the city. Having wrestled with God through lament, Jeremiah is more assured than ever of God. Ahead, the city David claimed his capital, is magnificently lighted by the setting sun. As the even breeze picks up, Jeremiah picks up his pace.

Let’s go back to that day, some 2500 years ago, and join Jeremiah once more… The heat of the day is over when Jeremiah starts back toward the city. Having wrestled with God through lament, Jeremiah is more assured than ever of God. Ahead, the city David claimed his capital, is magnificently lighted by the setting sun. As the even breeze picks up, Jeremiah picks up his pace. Ben Sasse, Them: Why We Hate Each Other and How to Heal (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2018), 272 pages including notes and an index.

Ben Sasse, Them: Why We Hate Each Other and How to Heal (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2018), 272 pages including notes and an index.