Bert called me into work early one day in 1974. Coming into the store, tying my tie as I walk over to the time clock, I saw Bert talking with Ed. He was one of the two brothers who owned the chain of stores. They called me over and told me I need to take a lie detector test. I was shell-shocked and didn’t have time to object before we were in the office where a stranger sat by a machine. They had me to sit down and the man, whom I’d never seen, explained how the machine worked and said he’d ask me questions. I immediately begin to recall eating a few bananas or grapes that were never paid for while moping the store at night.

Bert and Ed left the room. The man put clips on my shaking fingers, much like oxygen sensors used in a doctor’s office. A cuff, like one used for blood pressure, was applied to one of my arms. He started off with a bunch of easy questions, most of them personal, like name and age and hobbies and such. Then came the big one.

“Have you ever stolen anything from the store?”

Knowing my goose was cooked, I admitted eating a few grapes and a banana or two while there late at night mopping. I tried to rationalize saying there was no one to pay and pointed out that other times I weighed the fruit and left the money on a cash register. The man asked more questions about stealing money or about taking things out of the store. Finally, he got to cigarettes and spent some time asking if I or if I knew of anyone who’d stole cigarettes. My answers were honest. I knew of no one who’d stolen money or merchandise.

I was sweating like a pig when he finally finished. Thinking I was in trouble for my petty thief, I asked him how I did. “I’ll make a report, but I don’t think you have anything to worry about,” he said. “But what about the bananas and grapes?” “Don’t worry,” he said laughing. “That’s not what this is about.”

That night, while closing, Bert called me aside to tell me what this had been about.

In one of the other stores, they’d discovered a regular criminal ring. Another high school student, like me, who handled the tobacco products was stealing them blind. He would order more cases than needed. As this was back before barcode scanners, the only way to know how much product one sold was by how many items were missing from the shelves. According to Bert, the guy stashed the extra cases behind a dumpster. At night, when no one was looking, he’d stash the cases in his car. He’d been stealing five or so cases a week. Each case held 30 cartons. He sold the cases to someone who took the cases up north, where cigarette taxes were higher, to resale on the black market.

When the Wilson brothers discovered the ring, they brought in a lie detector detective. All all key employees (those who handled lots of money such as the managers, the cashier supervisors, as well as those who handled tobacco products) take a lie detector test. Even Bert and John had to take the test. I had no idea whether it was legal. but I was glad to have survived and to know that I wasn’t going to be fired for being the great grape thief.

About six months after I started working at Wilson’s, the guy who’d handled the cigarettes went off to college. Bert asked me if I’d be interested. I’m sure he was hoping he’d have me for several years in the position, which turned out to be the case. Furthermore, I was a good candidate because I didn’t smoke.

At this time, it was legal to smoke in North Carolina when you were fifteen, but the store’s policy was to use non-smokers to handle tobacco products. This was in the fall of 1973 and at that time, in North Carolina, a carton of regular cigarettes (ten packs) sold for $1.89. Do the math. Today, a pack of cigarettes will cost you more twice what a cartoon cost in 1973. Back then, if you wanted the longer cigarettes, you had to pony up a dime more for a carton. By the time I left the store in the summer of 1976, cigarettes had jumped to $2.39 and $2.49 a carton.

Every day I worked, I spent about half an hour filling the shelves with tobacco products. This also meant that I had to work more days to keep the shelves stocked. On Wednesday, it took me several hours as I first helped unload the truck. Then I rotated the shelves of product and fill the depleted ones. I would straighten up the tobacco room in the back and make a report on how many cartons of each cigarette we had in stock. Using that information, I made the order for the next week. I found it fun to project how many I felt we would sell. I knew people could become grumpy when we didn’t have their favorite bands.

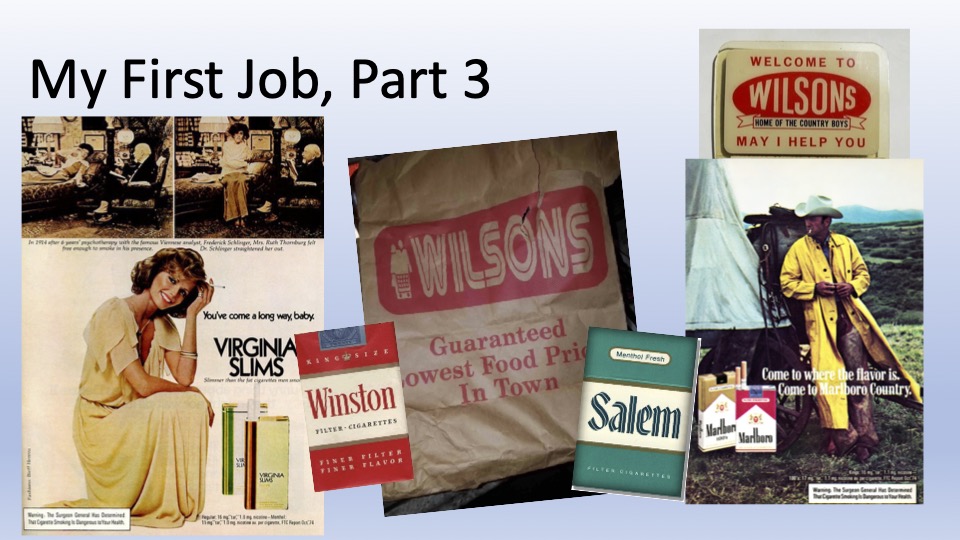

We sold lots of Winstons and Salems and Marlboros. If my memory doesn’t fail me, it seems I generally ordered 30 cases of each of those brands a week. We also sold a fair number of Camels as well as Virginia Slims, the choice cigarette for women. I often had to set up displays by the various Cigarettes. Marboros featured cowboys while Virginia Slims featured sexy women and the logo, “You’ve come a long way, Baby.” Having grown up with three grandparents who smoked heavily, I felt there was nothing sexy or macho about cigarettes.

In the summer, we sold more as tourists would stock up before heading back north. There were a few smaller brands that we might only sell a carton or two a week. As you wanted to keep your product fresh, we’d only have five or six cartons in the store at any one time. Occasionally a tourist would come in looking for some old brand, like a Chesterfield, and buy us out. Then, when the regular purchaser of that brand came in, they would be disappointed that we didn’t have any.

Another job that I assumed after about a year at the store was price changes. I was provided a printout of new prices and had a grocery cart with a bread rack tied to the top. In the part of the cart where the kids sat, I would stash the tools of the trade. A razor scraper, nail polish remover, rags, black magic markers, and a label machine. On my belt hung a price stamping machine.

I would go to each product, remove the old price. It the item was cans or glass jars with a metal top, the prices were generally stamped in ink. I’d put the cans on top of the bread tray shelf, pour nail polish removal on the rag and wipe off the products. If there were a lot of such cans to change, I’d get a little high from the smell. Next, I stamped the new price onto the top and placed the product back on the shelf. If it was boxes or frozen items, I would have to ink out the price with a magic marker and then place a label over it. Sometimes I would use a razor to scrape off a label.

When I first assumed this job in late 1973, after someone else had left for college or another job, I thought it was easy. I made the changes in prices in a hour or two each week. But if you remember the mid-70s, inflation began to skyrocket. By late 1974, it was taking me a full day and sometimes two to make all the changes. Instead of having a page printout, I began to have reams of papers. Some of the products that didn’t move off the shelf fast would have several changes on top. I found myself dreading certain changes, such a baby food. You can image how many jars of baby food a grocery shelf holds and to know that all the prices are going up by a cent or two. It’d take me hours.

In the summer of 1976, between my freshman and sophomore year in college, I accepted a job at the bakery. Bert asked if I’d like to stay on and continue to do the cigarettes. I agreed. I trained Tom to do the price changes. At the time I left, I thought I’d be back at the store in the fall, when school resumed. Bert and Ed discussed with me about becoming what was known as “the third man,” in a new store being built at Monkey Junction. When the manager and assistant manager were off, I’d be in charge and would be required to close the store a few nights a week.

The possibility of this new job as the third man sounded good to a college kid. But I finished my summer position at the bakery, the Production manager, called me into his office one day. Don told me he knew I was about to go back to school and wanted to see if there was a way for them to keep me employed. He suggested that I could have a second shift position and continue to go to school in the morning. He offered me a machine operator position and hinted that there might be a chance for me to become a supervisor. As they paid more than the grocery store was offering, I decided to stay with the bakery. I trained my friend Tom to take over the cigarette business at Wilsons. Two years later, I became a supervisor at the bakery.

Grocery Store Stories

Bakery Stories