Jeff Garrison

Bluemont and Mayberry Presbyterian Churches

Matthew 28:16-20

June 4, 2023

Introduction Before Worship:

Last Sunday was Pentecost. Today is Trinity Sunday. If you go by the liturgical calendar, this is the last “big” Sunday until we come to the end of the Pentecost season. Then, we start the year all over with Advent.

The Pentecost season, also called “ordinary time,” takes up the largest chunk of the church year. We’re reminded that our lives are mostly lived outside of feasts and holidays. Yes, there are times for big celebrations, but there are also normal times in which we walk in faith while doing the laundry, fixing dinner, paying the bills, or mowing the grass. God is God of all of it. Everything we do can be sacred, even the ordinary periods of life, if we are living for Christ.

Trinity Sunday

We enter this season on Trinity Sunday. The Trinity, this great mystery, reminds us that God is relational. The Trinity is about love—the love of the three persons within the Trinity as well as their love for all creation, as we’re embraced within the family.

We live in a world of sin and only in God can there be true love, so we need to accept the invitation to come draw close to God. As a Russian Orthodox meditation on the Trinity proposes, “outside the Trinity is hell.”[1]

The Trinity isn’t a philosophical or theological concept for us to master. It’s a mystery. We can’t fully comprehend it. Instead, we accept it along with the love God shows us. We’re to trust and live by faith.

Before the reading of the Scripture

You know, I love a good tomato sandwich. Right now, my tomato plants are just beginning to grow. But God willing, by late next month, they’ll be ripe tomatoes on the vine. Then, I will eat a tomato sandwich every day until they run out. I peel the tomatoes and slice ‘em thick; I want them juicy and messy. I take two slices of wheat bread, cover a side of each with Miracle Whip (I know for some folks, that makes me a heretic). Then I place the tomatoes, grind some pepper over it, creating a sandwich. If I want to be uptown, I add a little celery seed. Its good eating.

I tell you about tomato sandwiches because our passage can be envisioned as a sandwich.[2] Outside, the two pieces of bread, are about Jesus—one slice of bread being his authority and the other being his promise to be with us. Inside the sandwich, the thick tomato part, we find our marching orders. As followers of Jesus, it’s not about us. We’re not about glorifying ourselves. We’re here to do the work of the one whose authority extends over all heaven and earth, the one who also promises to be with us. Because of Christ’s power and presence, we can boldly take risks for the sake of the triune God, who calls us into a community to send us out to make disciples.

Today’s passage is the only place where Jesus uses the trinitarian formula, “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This comes from the very end of Matthew’s gospel.

Read Matthew 28: 16-20

The Great Commission

“The Great Commission.” At the end of Matthew’s gospel, Jesus commissions his disciples to take over. We learn three important things here: Who’s the boss. What we’re called to do. What help we’ll have with our tasks at hand. We don’t learn much about the Trinity. Instead, we’re called to an active faith. It’s more about doing than knowledge, and this passage is a call to action.

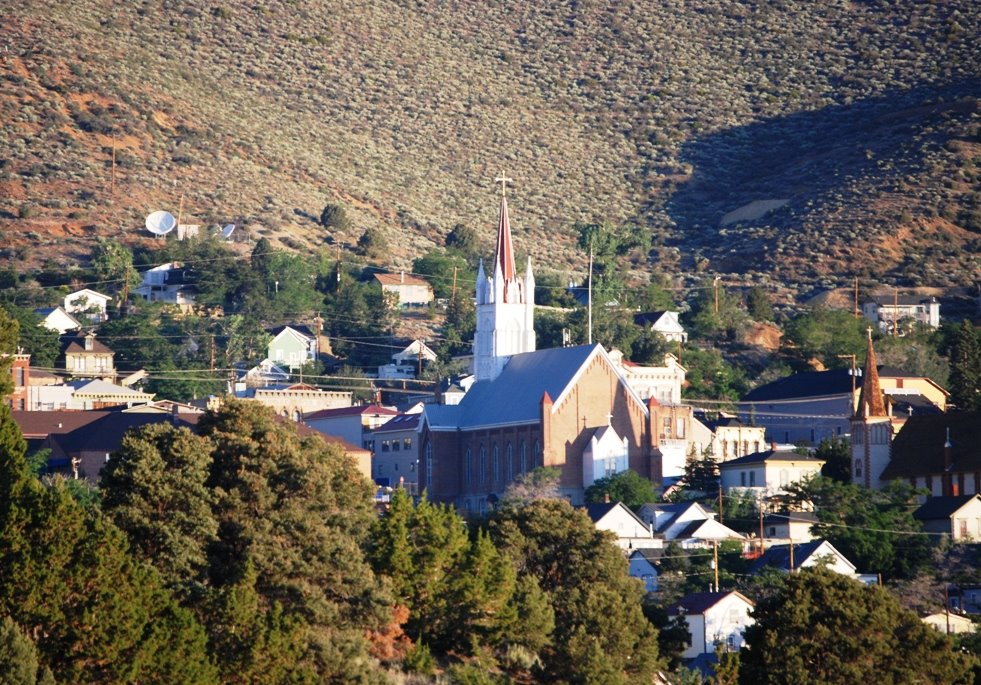

Mountaintop highlights

Many of the highlights of Matthew’s gospel occur on high places: mountains or hills. We have Jesus’ temptation in the mountains of the wilderness, the Sermon on the Mount, the transfiguration on another mountain, the great meal for 5,000 on a hill. Even the crucifixion occurred on a mountain, Mount Calvary. Now, once more, Jesus calls the eleven remaining disciples up on a mountain in Galilee. They’re back in their old haunts, where they focused their ministry, but instead of being with the crowds, they’re up high, on a mountaintop.

Worship and doubt

Interestingly, we’re told the disciples worshipped Jesus even though some doubted. This doubting may not imply what we think. Instead of questioning their belief, the word expresses a hesitation, or wavering. It’s like taking all this in, they freeze and are unsure of what’s happening.[3]

Matthew is realistic about human emotions. We don’t always understand what is happening in the arena of faith. Instead of having to understand everything or pass a theological test, we are called to trust. This is an important insight for those of us who sometimes harbor doubts. While some of the disciples didn’t understand, they listened and obeyed and followed Jesus. Accepting everything perfectly is not as important as doing the work for which we’re called.[4]

Now there’s only 11 disciples

We’re told Jesus gathered with the eleven. Of course, he started with the twelve, but Judas is no longer with them. Twelve is often seen as a perfect number, so maybe with eleven, Jesus acknowledges that he’s working with a less than perfect group. But that’s always the case because we are mortal and sinful, whether it’s the Apostles or us. Also note that by calling them the disciples at this point, and not Apostles or leaders. Jesus reminds them that they’re always students who will have to depend upon him.[5]

Disciple

With the remaining disciples gathered, Jesus tells them who’s boss. “All authority in heaven and earth have been given to me.” At the beginning of his ministry, the devil tempted Jesus on another mountain with authority over the earth, but now we learn that for the resurrected Christ, authority will extend far beyond that.[6] As the one in charge, Jesus is the one who can commission the disciples for the work at hand. And Jesus wastes no time issuing his orders. With four verbs—go, make, baptize, and teach— he sends them out to all nations.

All nations

Let’s unpack this a bit, first by looking at the destination, “all nations.” The promise to Abraham was for land and descendants, but Jesus owns all the world, so now the call is for all people, not just for a particular family.[7]

Jesus’ new family, the church, extends beyond national boundaries. While they may be national churches, there is no such place for an only American Christian, or a British Christian, or a Ugandan Christian. We are Christians, first and foremost. This idea of all nations means our work isn’t limited to just people like us.[8] The gospel needs to be heard by everyone. Paul later captures this vision when he writes, “there is no longer Greek or Jew, for we are all one in Jesus Christ.[9]

Our divided worl

Yet, we live in a divided world. We witness this every time we tune into the news. Whether it is another mass shooting in our country, Russia lobbing missiles at hospitals and apartment buildings in Ukraine, the fighting in Sudan, the burning of churches in India, the sniping between political parties in our country, brokenness surrounds us.

As believers in Jesus, the Prince of Peace, we must acknowledge this brokenness. But we also need to work to heal such brokenness. We’re to be instruments of God’s peace. We should cry out for justice especially for those unable to care for themselves. Let’s be honest, our present world does not represent the image of what Christ envisions in Scripture. It’s up to us to create such a representation of God’s kingdom for the world to see.[10] Sadly, like the disciples, we generally fall short.

Making disciples

Jesus calls us to make disciples. Interestingly, Jesus doesn’t say make Christians. Nor does he say to make Presbyterians. Instead, we’re to make disciples, or students of Jesus Christ. Making disciples isn’t instant conversion. It requires time.[11] Such folks may even have questions and doubts, as we see with the original disciples, but at the very least they are open to learning from the Master.

A three-fold nam

As we make disciples, we baptize them in God’s three-fold name: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Notice that this isn’t a baptism in three people, but in one. The name is singular (Baptized in the name of) followed by three distinct names that make up the Godhead.[12] In other words, those who sign up to learn from Jesus are connected to the Triune God. We’re part of that holy fellowship in which all followers are invited to join. And we’re to teach these people what Jesus commands.

Being a follower of Christ means we strive to keep Jesus’ teachings. God gives commandments to help us live in a way that will be affirming of God and of our brothers and sisters. But people won’t know what those commandments are unless they are taught.

The need for teaching

That’s right. People need to be taught. And judging a lot of what happening, it appears that before we go out into the world to teach, we need a refresher course in this country. We need to be taught that just because someone makes us uncomfortable because of the country of their birth, the color of their skin, or their political ideals, we still should respect and love them.

Jesus’ presence

We’re living in trying times, yet there is hope in this passage. In the last verse, after telling us that it’s our responsibility to make and baptize and teach disciples, Jesus reminds us that he is be with us till history comes to an end. Jesus is going to be with us wherever we go to do the gospel’s work. That’s the hope we take with us as we tell the good news and challenge such injustice. We’re not alone. We’ll get through such difficult time by remembering two essential things Jesus taught: Love God and love your neighbor.[13]

In closing, let me suggest that the call to all nations doesn’t mean we should all head out to some foreign land. Instead, because disciple-making is a long process, we’re to start where we are at by talking about the love of God in Jesus Christ and showing that love in our lives. Yes, some are called to the mission field. Some of us, if able, are to help support those on the mission field. But all of us are called to help disciple those around us by showing the love of the triune God: Father, Son and Spirit. Amen.

[1] Kathleen Norris, Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith (New York: Riverhead Books, 1998), 291.

[2] The idea of this passage being a “sandwich comes from Frederick Dale Bruner, The Churchbook: Matthew 13-28 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), 804.

[3] Chelsey Harmon, Commentary on Matthew 28:16-20. https://cepreaching.org/commentary/2023-05-30/Matthew -22816-20-3/

[4] I appreciate Enns insights on this theme. See Peter Enns, The Sin of Certainty: Why God Desires Our Trust More than Our “Correct” Beliefs. (2016, HarpersCollins Paperback, 2017). I reviewed this book here: https://fromarockyhillside.com/2022/08/29/catching-up-and-two-book-reviews/

[5] Bruner, 806.

[6] Matthew 4:8-10.

[7] Even Abraham’s nation was called to be a blessing to all other nations. See Isaiah 42:6.

[8] Burner, 816-820.

[9] Galatians 3:28 (edited to focus on nationality)

[10] One of the great ends of the Presbyterian Church is to exhibit the Kingdom of God to the world. Book of Order

[11] Bruner, 815-816.

[12] I appreciate Scott Hoezee’s writings on this passage for this insight. See https://cepreaching.org/commentary/2017-06-05/matthew-2816-20/

[13] Matthew 22:34-40.