Jeff Garrison

Bluemont and Mayberry Church

Daniel 4

September 12, 2021

At the beginning of worship

In Proverbs, we’re told that pride comes before the fall. It’s a central theme in scripture. We’ve been looking at the opening stories in the book of Daniel. All these stories warn us about hubris or pride. Thinking that we’ve done everything by ourselves, that we’re the master of our destiny, is flawed. As followers of the Master, we’re to give credit to God and to others who have helped us along the way.

Before reading scripture:

We’re continuing to work our way through the court tales[1] that make up the first half of Daniel. Today, we learn that Nebuchadnezzar has another curious dream. A dream about a tree. Not just any tree, but a beautiful tree that reaches to the heavens and provides shelter and food for all under its limbs.

But then the order is given. Cut the tree down. Unsettled, Nebuchadnezzar wants to know what this means. God’s warning him, but he doesn’t get it and find himself punished. For a period, he lives in a manner that should result in him being locked up in an asylum. Again, this chapter, like the past several, needs to be approached in its entirety. I will began reading Daniel’s interpretation, which gives you a drift of the entire story.

After the reading of Scripture

The desire to be more than moral

Kavi Usan was an ancient Persian king, but not as ancient as Nebuchadnezzar. He wanted to fly. A man of ideas, he had the four most powerful eagles within his kingdom brought to him. Each of these birds he tied to the legs of his throne. The throne’s legs not only supported the seat but rose high enough to support a roof that provided shade. On the top of these post, he tied strips of meat, which was just out of reach of the eagles. The eagles, in their attempt to reach the morsels of flesh, flew hard and pulled against their cords. Their efforts lifted the throne, which soared high into the sky. He headed toward China. But then, exhausted, the birds stopped trying to reach the meat. His throne crashed.[2]

Kavi Usan could have been a cousin to Icarus, the young Greek man of legend who supposedly built wings out of the feathers of birds to fly. Using wax to attach the feathers, he refused to heed the warning of father. Soaring higher and higher, he sailed close to the sun. The wax melted. He tumbled back to earth.

What are our limits?

These ancient stories remind us that there are limits to what an individual can do. Even the Wright Brothers, who perfected the airplane, learned from and built on the ideas of others.[3]

The myth of a self-made man (or woman) is just that, a myth. It’s more grounded in the philosophy of Fredrick Nietzsche than the Christian tradition. Nietzsche, by the way, is the 19th century philosophier who infamously proclaimed the death of God.[4]

The Danger of Pride and Ambition

Our tradition begins in the garden with Adam and Eve sampling the fruit of the forbidden tree because they want to be like God.[5] Curious beings, we strive to build and accomplish. It can be for the good. The problem arises from when we’re successful. Then we can beam with pride. Hubris takes over.

Ponder this for a moment. We seldom make or do anything by ourselves. Even building a birdhouse, I follow along with what my dad taught, which he learned from his dad. We might make improvements to the process, but we seldom do something entirely new. And anything of value we do, requires to assistance of others, in addition to the blessings of God.

Nebuchadnezzar’s pride

Nebuchadnezzar stands up on a roof of his palace. In a land where rain is seldom, roofs were often flat and served as patios or balconies. From there, he has a commanding view of this beloved city, Babylon.

Perhaps, from where he stood, he could see those famous hanging gardens watered by irrigation, one of the great wonders of the ancient world.[6] The fragrance of flowers and the lush fruit was a delight. He looked at the government buildings and homes and strong walls. Pride overtakes him. “Look at what I’ve done. I did this by my power, and it exists for my glory …” Before he finishes the sentence, God says, “Enough.”

The king had been warned in a dream. It was a dream that his own counsel could not interpret, so he calls for Daniel. In the second chapter, Daniel displayed the abilities his God had given him to interpret dreams. But Daniel didn’t want this job. Daniel’s smart. Who wants to give bad news to a king? Such messages are dangerous. But the Nebuchadnezzar of the fourth chapter appears to have mellowed. He no longer threatens to tear his advisors from limb to limb if they can’t interpret the dream. The furnace of the third chapter seems to have grown cold. The king encourages Daniel to be honest.

Daniel’s interpretation

In his dream there is a tree. This tree reminds us of other trees in Scripture, especially the trees along the river in the New Jerusalem. Those trees provide a year around supply of food.[7] This tree provides food and shelter and safety, which Nebuchadnezzar kingdom provided for his subjects. For a foreign king, Nebuchadnezzar doesn’t come off as a disinterested tyrant in Scripture.[8] As he has profited from his power, but so has his subjects.

But he’s warned. The God of the universe granted him the ability to build his kingdom. In the dream, an order comes from heaven that the tree is to be cut down. But the roots are saved. Daniel interprets this dream for the king. He’s the tree. God can have him removed at any time. Daniel, in verse 27, offers counsel. “Atone for your sins by doing what’s right and showing mercy to the oppressed and maybe, just maybe, your prosperity will continue.”

The king must have followed Daniel advice for a time, but then when he’s on the roof a year later, he just can’t help it. “I’ve done this,” he brags. Pride gets him, as it’s liable to get all of us. I stand looking at my garden, hoe in hand, and think I’ve done good. I brag about something I’ve built or accomplished (or how many pints of tomatoes have been put up) and forget to give credit where credit is due. It’s easy to fall into the trap of pride.

A lesson from the Appalachian Trail

I’ve told this story many times, but it is a defining story for my life. When I was hiking the Appalachian Trail, and getting close to the end, in central Maine, I got sick. It hit after lunch one day. Weak and exhausted. I didn’t think I was going to be able to make it over a mountain where a group of us were going to meet for the evening. I took a long nap on a boulder. I prayed for help.

Then I decided to pull out a small radio that I had mostly used to get weather reports. I turned into a Classic Rock station in Bangor and began to listen as I climbed the mountain. Soon, I was singing (something I can do in the woods by myself). “Heartbreaker” by the Rolling Stones can over the air. It got my legs moving.

That night, after having made camp and eaten dinner, I felt better. Before turning in to bed, I wrote in my journal, “Mick Jagger and the Stones got me over the mountain.” Then, about 3 AM, I woke to the realization that my prayer had been answered and I’d given the credit to a rock band. I was humbled.

The humbling of the most powerful

The most powerful man in the world in the 6th Century before Christ, Nebuchadnezzar had power that our politicians can only wish they had. It’s often said that the President of the United States is the most powerful person in the world. But the President’s power is limited. Every four years he (and maybe one day, she) must stand for election. Beside, our system of government is built with a system of checks and balances where congress and the courts looks over each other’s shoulders. Nebuchadnezzar had none of this! His power appeared unlimited.[9]

For the most powerful king on earth to become like a beast in the field makes his fall from grace even more dramatic. Talk about a humbling. We’re shocked by the description of this royal man living like a cow, with his long-matted hair and claw-like fingernails. He’s lost sanity. He lives this way for seven years,[10] before he looks up into the sky and acknowledges God. Our God is gracious even to those not of the chosen race. The dream had ended with a stump remaining, a reminder that not all is destroyed. There is hope a shoot from the stump will grow and restore the king to his throne.

Application for our lives

While none of us have the power of a Nebuchadnezzar, we still battle with pride. The antidote to this is humility, to acknowledge those who have helped us along the way and to constantly give thanks to God who makes it all possible. One of the outcomes of our faith should be a gratefulness and thankfulness, first to God, and then to all those who have help us along the way.

It would be my hope that Nebuchadnezzar, after he was restored to his throne, when he spent his evenings upon his roof patio, that he looked out upon his land. Instead of thinking that he’s done it all, he acknowledges the role God and the thousands of Babylonians and others whom his nation had conquered, folks like Daniel, who helped make him great. And maybe afterwards, having thanked God, he sat at his desk and wrote a few thank you notes. Amen.

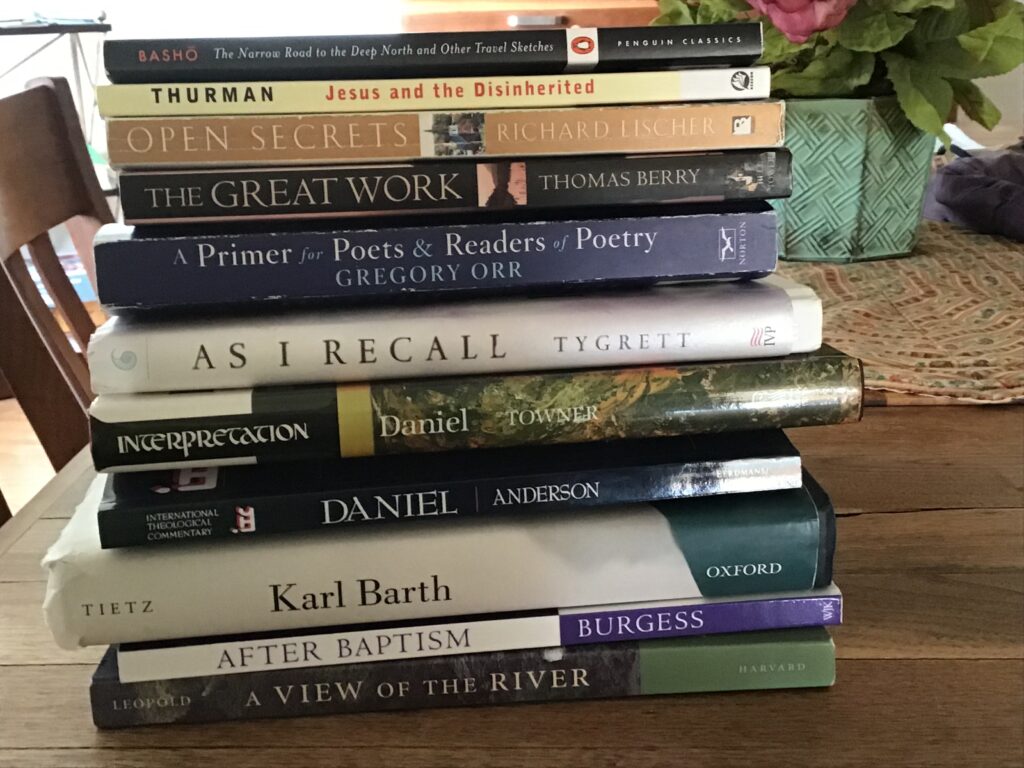

[1] See W. Sibley Towner, Daniel (Atlanta, JKP, ), 59

[2] Chet Raymo, The Soul of the Night: An Astronomical Pilgrimage (1985, Boston, MA: Cowley Books, 1992), 171.

[3] David McCullough, The Wright Brothers. (. )

[4] In his famous fable, his main character, Zarathustra proclaims that God is dead. Nietzsche believed that humanity, freed from morals, had the capacity to become greater. See Frederick Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1885).

[5] Genesis 3:5

[6] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanging_Gardens_of_Babylon

[7] Revelation 22:2. For a comparison, see Ezekiel 47:12.

[8] Temper Longman III, Daniel: The NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rap

ids, Zondervan, 1999), 123.

[9] Longman III, 124.

[10] Scripture says, “seven times.” See Daniel 4:25.