Hannah Anderson, Humble Roots: How Humility Grounds and Nourishes Your Soul

(Chicago: Moody Publishing, 2016), 206 pages.

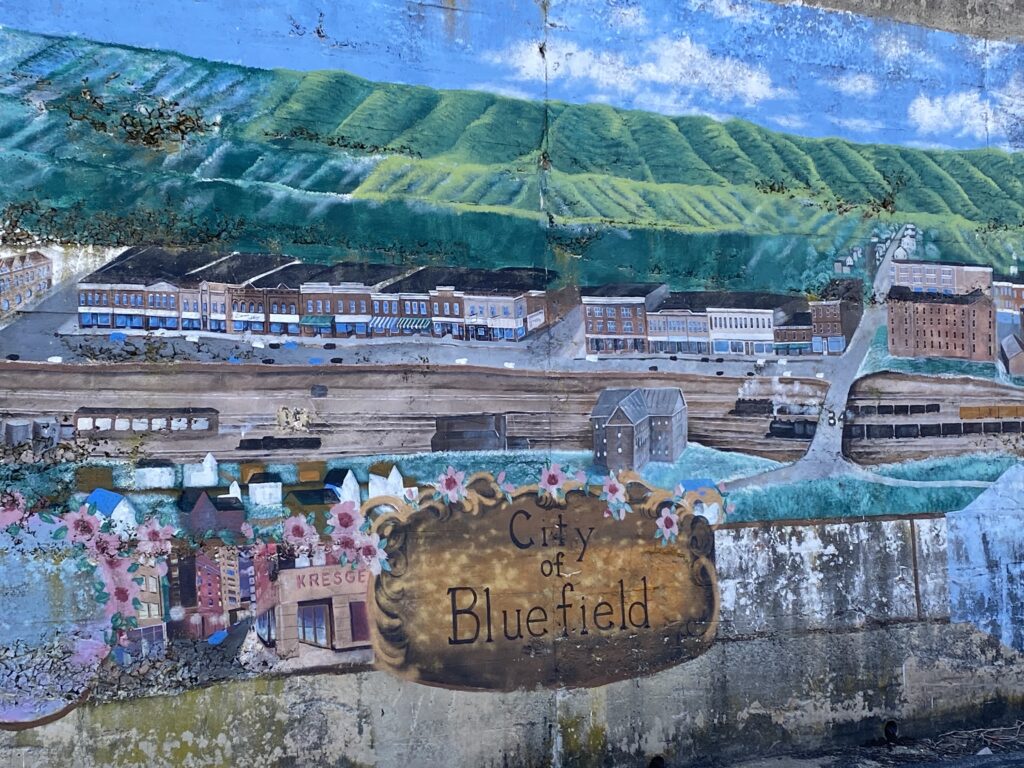

I heard Anderson at the HopeWords Writers Conference I attended in April in Bluefield West Virginia. Another speaker referred this book of hers for its ability to create a sense of place, which is why I chose it as the first of hers to read. Anderson lives with her family on a small farm near Roanoke, Virginia. This book consists of eleven essays that draw on the natural world, especially the rhythms of agriculture. Among the topics Anderson explores include: planting seeds, cultivating grapes and apples, raising honey, appreciating vine-ripe tomatoes, the role of pollinators, and dealing with thorns and thistles.

In each of these essays, Anderson also explores aspects of our lives and our faith. Some of the themes she explores include having enough and being blessed, trusting God, remaining humble, spiritual maturity, and being an image bearer. Each essay comes back to being humble, a topic she addresses throughout the book. Humility is a challenge for if we think we can accomplish it by ourselves, we have already lost the battle. Just thinking we can overcome pride is prideful. We must depend on God even for our humility, yet we can see how it works through the natural rhythm of life that surrounds us.

A few favorite quotes:

“Fascinating, while humans were made to rule over the earth, we were also made from the earth. And perhaps even more significantly, we only came alive by God’s Spirit. Without God’s breath in us, we are nothing but a pile of dirt.” (page 65)

When we use fear to persuade a person to decide ‘before it’s too late,’ we make God like a cosmic bully who is just waiting for the opportunity to strike them down.” (page 112)

“The problem with privilege is that we rarely see our own. Because we only know our own experience, we rarely recognize how much we have been given and how much those gifts have smoothed our way.” (page 142)

I would recommend this book to anyone interested in living a worthwhile life, especially those who are interested in our role in the world.

Others books that I reviewed of authors at the conference:

Makoto Fujimara, Art & Theology

Malcolm Guite, In Every Corner Sing

I still have books to read by Winn Collier and am finishing up a collection of essays by Lewis Brogdon.

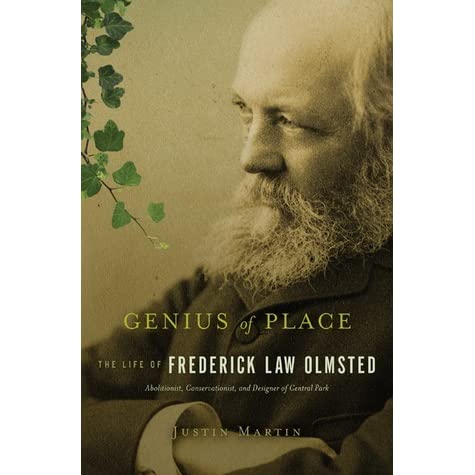

Justin Martin (Richard Ferrone, narrator), Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmstead

(2010, Audible, 2014, 18 hours and 48 minutes).

Olmstead, A Man of Accomplishments

Frederick Law Olmstead led an incredible life. He started out as a surveyor, then went to sea, traveling from the east coast to China, then with the health of his father became a farmer, a traveling correspondent before entering the new field of landscape architecture with his work on designing New York’s Central Park. While he would continue in this field the rest of his life, he took time out to run the United States Sanitary Commission (a Red Cross forerunner) during the American Civil War and later operated a gold mine in California. While in California, he became enthralled with Yosemite and lobbied for the sight to be saved for future generations years before John Muir. His travels in the American South changed his mind on slavery and his books on these travels were probably second to Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin in building abolitionist support. Because of this writing popularity in Great Britain, he’s partly credited with keeping England out of the American Civil War.

Influence on Landscape Design

But what Frederick Law Olmstead is mostly known for is his landscape designs. He felt parks should be for the people and that they should help our emotional state by allowing city dwellers an opportunity to be in nature. Many of his parks and estates still exist and he influenced generations of landscapers who followed him. Not only does he have Central Park (which he designed with Calvert Vaux) to claim, but Brooklyn’s Prospect Park along with parks in Boston, Chicago, Buffalo, Rochester, and a host of other cities. He influenced park designs in San Francisco and other places. With his work in Buffalo, he helped preserve Niagara Falls (sadly, he came upon this a little late, but it appears it was more of a tourist trap in the 19thCentury than today). His landscape ideas shaped Chicago’s 1893 World’s Fair and he designed the landscape for the grounds of the Biltmore House near Asheville, North Carolina. The later also helped establish forestry as a scientific study in America.

Failure in his early life

In a way, Olmstead’s early life was full of failure. Thankfully, he had a wealthy father who helped his son out on many occasions, such as buying farms for him and sending him on fact-finding journeys through Europe. These trips helped prepare Olmstead for his career. His life also had its share of sorry, including his brother’s early death and the deaths of friends. He would later marry Mary, his brother’s wife, and adopt their children. Mary would also give birth to several children, two who died young. His adopted brother’s son, John, and his own natural son, Frederick Law Olmstead, Jr, would continue their father’s role as premier landscape architect through the first half of the 20th Century.

Olmstead was always interested in words and would often look for the right word for a project. Many words we use today came from Olmstead and his associates. His first park in Boston was a marshy area in which he named “the Boston Fens.” Fen is an old English word for marsh and lives on now in baseball with “Fenway Park.”

Sadly, Olmstead began suffering from some sort of dementia after the Chicago World’s Fair and the creation of Biltmore. He would spend his last years in an institution and died in 1903.

My recommendation

I have been aware of his name for some time. I knew of his work for the Chicago’s World’s Fair from Erik Larson’s The Devil in the White City. I also knew he designed the Biltmore and Central Park. I had some ideas of his additional work through Nick Offerman’s book, Gumption. He led an amazing life, using his influence to save Yosemite, helping to end slavery, and providing a framework for what would become the American Red Cross. I recommend this book!