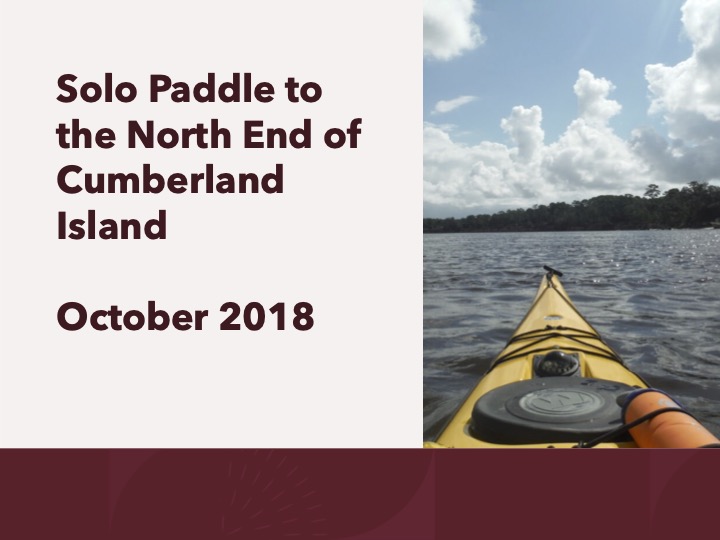

A soft light glows outside in the darkness. It could be a dying street light, except there are no streetlights on this island. I check the time. It’s a little before 6 AM. Time to get up if I’m going to beat the tide change. I pull on my pants and crawl out of the hammock. Sliding into flip-flops, I stand and turn around to a beautiful view of the nearly full moon setting across the marsh to the west. Its light reflects off the ripples on the waters of the Brickhill River. I look at the shoreline. The tide is coming in strong. I’ll need to be on the water soon if I’m to make the fourteen miles back to the landing at Crooked River State Park without fighting the current.

Heading back to the mainland

In the dark with only the moonlight guiding me, I stuff my sleeping bag and hammock into their sacks and stow both into the holds of the kayak. I pack my stove and percolator. With not enough time for coffee, I skip it figuring I can pick up some later on my drive home. Dropping the food bag that’s hung from a branch, to keep it safe from raccoons, I take out a couple of granola bars and a pear for breakfast. I eat one of the bars while watching the moon set. What little light I enjoyed is gone with sunrise still 45 minutes away. Taking out a flashlight, I stow everything in the kayak and make a last tour of my campsite. Then I slide the kayak down the bank and into the water, crawl into the cockpit, and begin paddling.

In less than 30 minutes I’ve passed Table Point. When I paddled here two days earlier, the tide had turned by the time I arrived here and it took me 90 minutes of hard paddling to make it to the campsite. I’m making good time. I look behind me and catch the opening rays of the sun as it rises over Cumberland Island. I take out the pear and eat it, enjoying the splendor. When I resume paddling, I notice the large covered submarine dry-dock at the Kings Bay Naval Station. In the low light, it looks remarkably similar to Noah’s Ark, floating beyond the marsh grass that separates the Brickhill River from the Intracoastal Waterway. It’s ironic, I muse to myself, that each submarine carries almost as much destructive power as that ancient flood.

Travels to Cumberland

I have spent the last two nights camping on Cumberland Island National Seashore. This is my second trip to the island. The first trip, two years earlier, was to Sea Camp on the south end of the island. That site is served by a ferry from St. Mary’s. It’s close to the beach and has potable water, flush toilets and hot showers. We spent a lot of time soaking up rays on the beach, swimming in the surf, as well as exploring the ruins of Dungeness, a grand home built by Thomas Carnegie. It burned in the 1950s.

The Carnegie Influence on the Island

In the late 19th Century, Thomas Carnegie, the brother of Andrew, purchased much of the island and had a massive winter home built at the site of an earlier Dungeness mansion. Thomas Carnegie died as his mansion was being completed, but it was occupied by his wife Lucy. In time, as each of their children married, Lucy granted them land on the island and a stipend to build homes of their own.

My campsite for the weekend was on a bluff along the Brickhill River. The wilderness site can hold six groups, but there are only three other campers the first night. These guys, students at Georgia Tech, had come over on the ferry and peddled bikes the ten miles along sandy two-track dirt roads to camp here. We chat for a bit and I learn they are planning on leaving early on Sunday in order to catch the 10:30 AM ferry to St. Marys.

The Paddle over and Plum Orchard

On Saturday, as I left Crooked River, paddling in the rain, my first stop was at Plum Orchard, one of these magnificent homes. Thankfully, by the time I arrived, the rain had stopped. This home, built by George and Margaret Thaw Carnegie, was the first of the island mansions constructed by the Carnegie children. The 24,000 square foot home was seasonally occupied until the 1960s with Thomas and Margaret’s granddaughter and husband being the last occupants. Today, the home is a part of Cumberland Island National Seashore and the National Park service offers tours. After eating lunch, I stuck around for a tour. It was well worth it, even if it meant the tide turned and my paddle to the campsite was more difficult. The home features a grand entryway, a formal dining room, modern bathrooms, an indoor squash tennis court, a women’s parlor and a men’s gun room that displays trophy heads of various animals bagged by the Carnegies. It is magnificent.

First Night

Fires are not allowed at this site, so after setting up my camp, I fire up my gas stove and use it to prepare chicken and rice for dinner. I watch the setting of the sun, sipping on bourbon, then retreat from the bugs into the security of my hammock where I read for an hour with the use of a flashlight. Then I turn it off and go to sleep.

As it was still warm in the evening, I left the fly off my hammock in order to receive the best breeze. But at 3 AM I wake to the rustling of palm leaves and distant thunder. The moon and stars are no longer visible. I quickly get up and position my fly over my hammock. The rain comes as I put in the last of the stakes into the ground. I crawl back into the hammock and fall asleep to the sound of rain.

I sleep in till nearly 7:00 AM on Sunday morning. Getting up in the dawn light, I perk coffee and boil hot water for oatmeal. I notice my neighbors have already left.

Sunday Morning Exploring

After breakfast, I set off on a hike to the old settlement on the northern end of the island, about four miles away. It’s warm and muggy, and I’m serenaded by insects, songbirds and a distant woodpecker providing the bass. About half way to the settlement, a shower passes by cooling me off. When I arrive at Terrapin Point, I stop for a few minutes on the high bluff overlooking what used to be the Cumberland Wharf. A large pod of dolphins feed in the shallows as a barge makes its way south along the Intracoastal Waterway. In the distance, I can see the Sidney Lanier Bridge from Brunswick to Jekyll Island.

My hope was to be at the old First African Baptist Church by 10 AM, but I am a few minutes late. The cornerstone indicates that it was built in 1893, but I later learn that was when the first church was constructed out of logs. It was rebuilt out of timber in 1937. I step into the old building. It’s small, with only eight short pews. Taking out my smartphone, I am pleased to have a signal. I log into the streaming service of Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church in time to catch an excellent sermon by our Associate, Deanie Strength. As I listen, I think about those who in years past worshipped here and that it is good the gospel is again heard in these walls.

HIstory of the settlement

The residents of the Settlement were former slaves. They lived where they did to work for the hotel that used to sit on the north end of the island, as well as to work for the Carnegies who turned much of the island into their private winter playground. The community dwindled after the hotel closed, with a few people hanging on to work as servants in some of the islands homes. Today, the church and one home remains open by the National Park Service.

In 1996, a hundred and three years after the church was first built on this site, it became the setting for the late John Kennedy Jr’s and Carolyn Bessette’s private wedding ceremony. Tragically, two years after their marriage, both were killed in a plane crash off Martha’s Vineyard.

After listening to church, I eat lunch and then hike back to the camp, taking the Terrapin Point and Brickhill Bluff trails. At times, from high bluffs, I’m afforded wonderful views of the marsh. Other parts of the trail move deeply into the woods of this maritime forest. I am amazed at the size of some of the longleaf pines. In addition to pines and live oaks, the most abundant trees, hickory and magnolias are also common. I scare up a few feral hogs that grunt as they run away, along with a wild turkey and an armadillo that makes all kinds of racket as it rushes through dense growth of saw palmetto.

A restful afternoon

It’s about two o’clock when I arrive back in my campsite. I rest for a few minutes, reading David Gressner’s Return of the Osprey. As I read, I notice an osprey hunting out over the Brickhill River. For the longest time, the bird never dives for a fish, but when it finally does, he misses. The bird comes up out of the water flapping, nothing in its talons. It shakes its wings as if to shake off his missed lunch. In reading this book I learn that mature birds generally catch their prey fifty percent or more of the time. That’s a pretty high percentage. Either my bird was having a bad day or it was young and just learning to dive for fish.

After resting, I take my chair, book, and some snacks, and hike the two miles out to the beach. Along the way, I pass several fresh water ponds. In one an alligator is sunning and as I walk by I catch sight of the tail of a large snake slithering down into the water. I spend nearly two hours on the beach enjoying the sound of the waves as I read and nap. At 5:30, I start back, wanting to be able to fix dinner and prepare for the evening before dark. Knowing it’s going to be a long paddle in the morning, I am in my hammock sleeping shortly after watching an amazing sunset.

This slightly edited post originally appeared in The Skinnie, a magazine published on Skidaway Island, Georgia. The opening page of the article is to the right. When I wrote this article, I was the pastor of the Presbyterian Church on Skidaway.

For another kayak adventure of mine on Cape Lookout, click here.

Planning a trip to Cumberland Island

To visit Cumberland Island, camping sites (both in developed sites and wilderness locations) must be reserved through the National Park Service. Check out the Cumberland Island website at or call (912) 882-4336. Cumberland Island Ferry has the concessions for ferry transportation to and from the south end of the island. Their schedule varies depending on the season. Boats (motored and kayaks) can be launched from St. Mary’s or Crooked River State Park. If paddling, know the tides especially in the Crooked River where the tide currents can be faster than most people can paddle! There is also a rather pricy lodging available at the Greyfield Inn, a former Carnegie mansion. To stay there, the Inn arranges a shuttle from Amelia Island, Florida.