What are you reading this days? Looking for a good book while you isolate yourself? Here are three books from books I recently read. It’s by sheer accident that two of them discuss Epictetus (but different parts of his philosophy):

P. M. Forni, The Civility Solution: What to Do When People are Rude (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2008), 266 pages including notes.

The late P. M. Forni was the founder of the Civility Institute at John Hopkins University. In this short book, he deals with issues we face all the time, rude people. He encourages his readers to take the high and honest road when dealing with such folks. It’s the only way to build a more civil world.

In the first chapter, Forni defines rudeness as a disregard for others and an attempt to “control through invalidation”. He lists the costs rudeness has for individuals, the economy, and society: stress, loss of self-esteem, loss of productivity, and the potential of violence. He also discusses the cause of rudeness, which is simplifies as a bad “state of mind”.

In the second chapter, Forni presents and explains how to prevent rudeness by listing and explaining eight rules for a civil life:

Slow down and be present in your life

Listen to the voice of empathy

Keep a positive attitude

Respect others and grant them plenty of validation

Disagree graciously and refrain from arguing

Get to know the people around you

Pay attention to the small things

Ask, don’t tell

In the third chapter, Forni writes about how we can “accept real-life rudeness.” He quotes Epictetus, who encourages us to want things to happen as they happen for a life to go well. After all, we can’t control other people, and if we expect that there will be rudeness in life, we won’t be surprised. But once we accept the situation, then we can act upon it, which may be to remove ourselves or to refuse to be react. “Rudeness is someone else’s problem foisted on you,” Forni notes (62). Once we accept reality, we may choose to respond appropriately and even assertively to redirect the situation.

In the fourth chapter, Forni writes about how we respond to rudeness, but does so by beginning with a wonderful (and very rude example) from two 18th Century British politicians. Scolding his rival, John Montagu cried, “Upon my soul, Wilkes, I don’t know whether you’ll die upon the gallows or of syphilis.” Wilkes responded, “That will depend, my Lord, on whether I embrace your principles, or your mistress” (67). Forni suggests that when we encounter rudeness, we cool off, calm ourselves, don’t take it personally (most often it’s not personal), and then decide what we need to do. While we do not need to respond to all situations, we don’t want to ignore all situations, either. When we do decide to confront, we need to state the problem, inform the offending party of its effect upon you, and request such behavior to cease. Forni then lists special situations such as bullying, rudeness at work, and rudeness with children.

The second half of the book consists of a series of case studies. Starting with those close to us, Forni offers examples of rudeness that we might face along with a solution to how we might confront the behavior. Other chapters deal with rudeness from neighbors, at the workplace, on the road, from service workers, and within digital communications. While these chapters contained many important ideas and examples, it essentially applied the principals laid out in the first half of the book. It’s too bad that Forni is no longer with us. He could have updated this issue with a section on political rudeness.

Another of Forni’s books have been on reading list for some time. This book was brought to me by a colleague, who had found it at a book exchange and brought it for me, knowing of my interest in civility. I was glad to read it and would recommend it. I also look forward to reading more of Forni’s writings.

###

N. T. Wright, Surprised by Scripture: Engaging Contemporary Issues (New York: HarperOne, 2014), 223 pages including a scripture index.

N. T. Wright, Surprised by Scripture: Engaging Contemporary Issues (New York: HarperOne, 2014), 223 pages including a scripture index.

This is a collection of twelve lectures crafted into independent articles addressing many contemporary issues in the world: the debate over science and religion, the role of women within the church, the environmental crisis, evil, natural disasters, politics, and the future. For those who have some familiarity with Wright’s theology, you will see many of these topics addressed with his recognizable theology of the cross and resurrection ushering in a new era in which we now live. The resurrection is the eighth day of a new creation brought to us by God the Redeemer (paralleling the new creation in Genesis). For Wright, the purpose of salvation is to restore us to stewards of creation (36). Wright is also critical of the adoption of Epicureanism during the Enlightenment, which allowed us to do away with “God.” The result is that we’ve gone back to the old gods of Aphrodite, Mammon, and Mars. In other words, we’ve “got rid of God upstairs so that we can live our own lives the way we want…. And have fallen back into the clutches of forces and energies that are bigger than ourselves… forces we might as well recognize as god” (149-154). Wright also draws some interesting comparisons from his native home in the United Kingdom to the religious situation in American. He points out how the “right” is seen as the savior of religion in American, and how it’s the “left” in Britain that for the past forty years have tried to restore religion to the public life (164). The closing essays looks at the future. While debunking ideas such as the rapture and others end world scenarios popularized by the “Left Behind” series, he leaves his readers with a more hopeful vision of the future. I enjoyed these essays. They left me with a lot to ponder and I recommend the book to others interested in how the Christian faith might inform our lives and world today.

###

Laura Davenport, Dear Vulcan: poems (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2020), 63 pages.

Laura Davenport, Dear Vulcan: poems (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2020), 63 pages.

There is much about the South in these poems. Her grandfather’s grandfather walks back from Richmond in the spring of 1865, burying his burdens along the way. A girl becomes a woman in the industrial city of Birmingham, Alabama, with its mile-long coal trains snaking around closed steel mills. While the title poem, “Dear Vulcan,” is set in Birmingham, Davenport explores many places across the region. There are urban and rural settings, places inland and others by the ocean. Hell is seen in a basement pool hall. The August thunderstorm at night “washes summer metallic edge from the air.” There’s the city without women, which keeps reappearing, populated by a boy experiencing the world. Sexuality is explored in parked cars, church basements, and by a married couple drawn to each other in bed after painting the room. In each poem, the reader stumbles upon more pleasant surprises.

While I found much about the South in these poems that I related to, the one missing element was race. Birmingham was not just the Southern Pittsburgh; it was also the city of Bull O’Conner and the 16th Street Baptist Church where four young black girls waiting for their Sunday School class to begin, died in a racist firebombing. Perhaps, one could hope, this could be forgotten and buried or painted over, and we could have a South where race no longer mattered. But that’s my bias, instilled by growing up during the Civil Rights era. But maybe the absence of race (as in women in the poems in cities without women) is that the South often struggles to ignore that which it doesn’t want to face. In my own personal life, I am still amazed that I could live in a city in Virginia for three years, (this was before they segregated schools) and never realize that we (whites) made up only 20% of the population. For the South as a region to come of age, it’ll have to learn to face the unspeakable. In the meantime, children become adults and must experience the world around them which Davenport captures beautifully.

I met Davenport through a writer’s group that I’m in. I was hoping to catch her book release, but it was the day after I had flown back from Austin, Texas, just as the country was shutting down over the fear of COVID-19. As I had been around several hundred of my “best friends” inside two airplanes, I decided it was best if I self-quarantined. I missed the reading at the Book Lady Bookstore but was able to pick up a signed copy of the book thanks to the “Booklady” (who had an employee drop the book off at my office on his way home). How’s that for service!

###

Jesse Cole, Find Your Yellow Tux: How to be Successful by Standing Out (Lioncrest Publishing, 2018), 303 pages, some photos.

Jesse Cole, Find Your Yellow Tux: How to be Successful by Standing Out (Lioncrest Publishing, 2018), 303 pages, some photos.

Robert A. Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power (New York: Alfred Knopf, 2012), 712 pages including notes and sources and 32 inserted pages of black and white photos.

Robert A. Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power (New York: Alfred Knopf, 2012), 712 pages including notes and sources and 32 inserted pages of black and white photos. David Lee, Mine Tailings (Boulder, UT: Five Sisters Press, 2019), 79 pages.

David Lee, Mine Tailings (Boulder, UT: Five Sisters Press, 2019), 79 pages.

James H. Cone, (Marynoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2011), 202 pages including notes and an index.

James H. Cone, (Marynoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2011), 202 pages including notes and an index. David Zucchino, Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020), 426 pages including notes, bibliography, and index along with 12 additional pages of prints.

David Zucchino, Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020), 426 pages including notes, bibliography, and index along with 12 additional pages of prints.

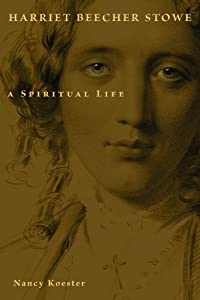

Nancy Koester, Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Spiritual Life (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2014), 371 pages, B&W photos, notes.

Nancy Koester, Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Spiritual Life (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2014), 371 pages, B&W photos, notes. Eric Goodman, Cuppy and Stew: The Bombing of Flight 629, A Love Story (San Francisco: IF SF Publishing, 2020), 220 pages with a few photographs.

Eric Goodman, Cuppy and Stew: The Bombing of Flight 629, A Love Story (San Francisco: IF SF Publishing, 2020), 220 pages with a few photographs. High tide last night was at 9 PM. I went out around 8 PM, catching the last of the sunset and then watching the moonrise, paddling around Pigeon Island (approximately 5 miles). The tide was very high and I could easily go through the marsh. Here’s a poor quality photo taken with a smart phone from a kayak that was slightly rocking from the gentle waves. The photo doesn’t do the view justice. It was an incredible sight and the paddle was delightful

High tide last night was at 9 PM. I went out around 8 PM, catching the last of the sunset and then watching the moonrise, paddling around Pigeon Island (approximately 5 miles). The tide was very high and I could easily go through the marsh. Here’s a poor quality photo taken with a smart phone from a kayak that was slightly rocking from the gentle waves. The photo doesn’t do the view justice. It was an incredible sight and the paddle was delightful

N. T. Wright, Surprised by Scripture: Engaging Contemporary Issues (New York: HarperOne, 2014), 223 pages including a scripture index.

N. T. Wright, Surprised by Scripture: Engaging Contemporary Issues (New York: HarperOne, 2014), 223 pages including a scripture index.