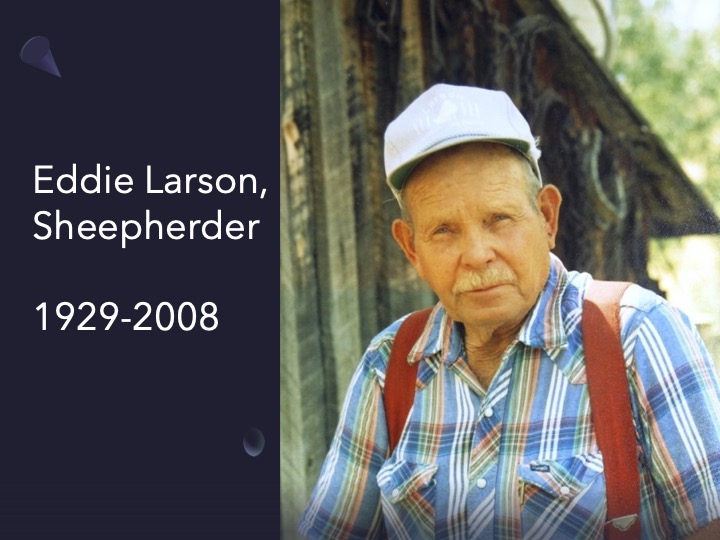

I wasn’t going to post this week. I’ve been busy. A contractor is preparing to add a large addition to our house and I’ve been trying to get the garden in, and I’ve done volunteer work, and I have all kind of other excuses. Then, today, I learned of the death of Timothy Keller. After a long battle with pancreatic cancer, our last enemy death finally claimed him this morning. In recent days, knowing this time was short, Keller (and his son) sent out tweets telling of his struggles and his hope to soon be with his Savior.

I first became familiar with the ministry of Timothy Keller while on a month Sabbatical for Preachers interested in how literature can inform our preaching led by Neil Plantinga at Calvin Theological Seminary in the summer of 2003. In discussing Franz Kafka’s writings, he played a sermon that was in a serious Keller preached on the hopeless many feel in today’s world. In these sermons, in addition to scripture, Keller depended upon Kafka’s The Trial. I was impressed and had never imagined using Kafka in the pulpit.

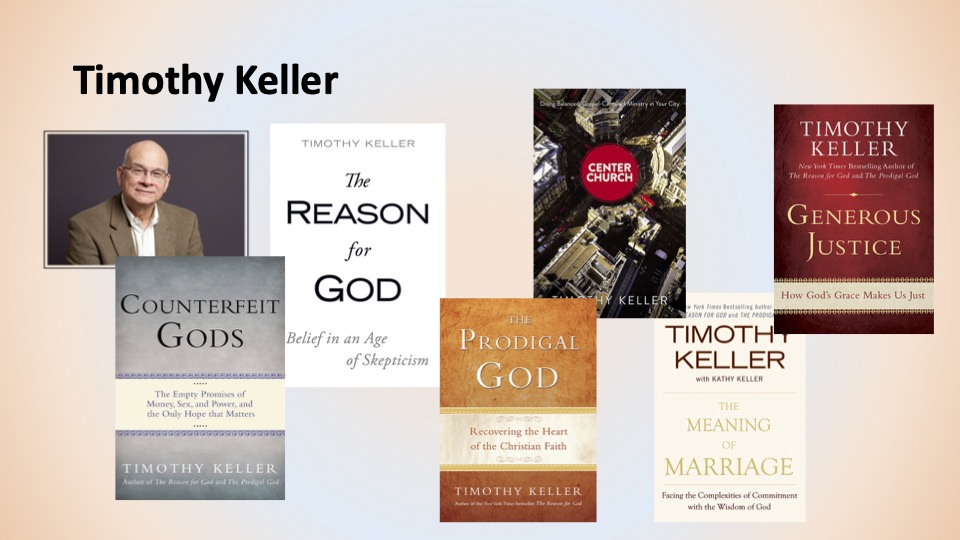

While I never met Keller, I heard him speak once. Even though we are from different Presbyterian denominations, I once worshipped at the church he founded, Redeemer Presbyterian in New York City. But it was summer, and he wasn’t preaching. I’ve read six of his books. In addition to the two below, which I first reviewed in another blog, I have read and have on my shelves The Reason for God, The Meaning of Marriage, Generous Justice: How God’s Grace Makes Us Just, and Centered Church: Doing Balanced Gospel-Centered Ministry in Your City. I may not have always agreed with him, but I learned a lot from him. His arguments were always compiling and his gracefulness came through in his writing as well as in his speaking.

May Timothy Keller rest in peace.

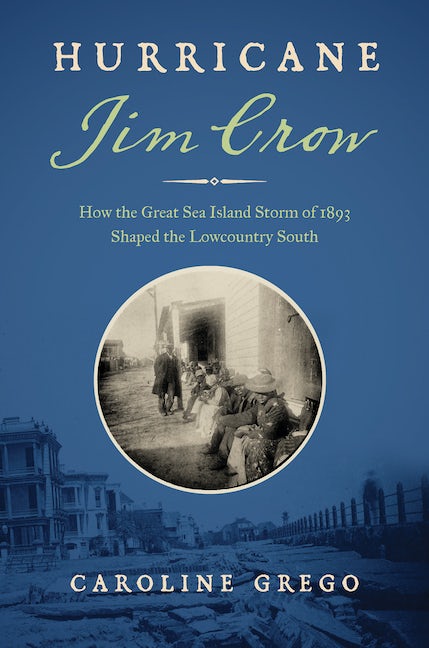

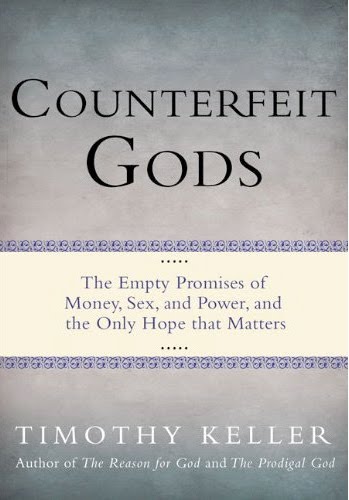

Counterfeit Gods: The Empty Promises of Money, Sex, and Power, and the Only Hope that Matters

(New York: Dutton, 2009), 210 pages

Idolatry is not just a failure to obey God, it is a setting of the whole heart on something beside God. (171)

Idolatry is prevalent in our world, our communities, our churches, and our individual lives. As Keller points out over and over, idols are not necessarily bad things. In fact, they are seldom bad. They are generally good things (family, sex, money, success, and even religion), but when we look to them to “satisfy our deepest needs and hopes,” they fail us. They become a counterfeit god. (xvii, 103). I found this to be a powerful and challenging book. It was published following the 2008 financial melt-down, written by a pastor whose church on Manhattan draws many of the investment bankers that were at the forefront of the crisis.

Using Biblical stories as illustrations, Keller attempts to expose the idolatry of our lives. For idolatry of the family, he draws on the story of Abraham and how the old man pinned his hope for a legacy on Isaac, essentially making his son into an idol. For sex, he explores the story of Jacob’s courtship with Rachel and Leah. For money and greed, he looks at the call of Zacchaeus. For success, he looks at Naaman, the leper, who question Elijah’s method of healing. For success, he looks at Nebuchadnezzar’s dream of clay feet. His examination of how “correct religion” can become an idol leads him into the story of Jonah. And finally, he looks at how we need to replace our idols with God by exploring Jacob’s wrestling.

There are two levels to our idolatry according to Keller. We all have surface idols that mask our deeper idols. These surface idols are mostly good things, but they become idols because we place our ultimate trust in them as we strive to satisfy our deeper longings for power, approval, comfort or control. (64) We can fight against the surface idols, but new ones will pop up unless we address our deeper needs, which can only be handled by replacing such idols with a total trust in God.

Keller confronts our worship of success. He even challenges how some place total trust in “the free market.” “The gods of moralistic religion,” he proposes,” favors the successful.” It could be argued that such folks are attempting to earn their salvation. But the God of the Bible comes down to earth to accomplish our salvation and give us grace. (44) Later in the book he writes that the “Biblical story of salvation assaults our worship of success at every point.” (94) He challenges Adam Smith’s theory of capitalism for “deifying” the invisible hand of the market which, “when given free reign, automatically drives behavior toward that which is most beneficial for society, apart from any God or moral code.” He ponders, in light of the financial crisis, if the same dissatisfaction that occurred with socialism a generation earlier might also occur with capitalism. (105-106)

Keller also challenges our political and philosophical ideals, especially those that we place above our faith in God. Straddling the political fence and refusing to place himself on the right or left, as a Republican or Democrat, he observes that a fallout of us making idols out of our philosophy/politics may be the reason why when on group loses and election there is often an extreme reaction.

“When either party wins an election, a certain percentage of the losing side talks openly about leaving the country. They become agitated and fearful for the future. They have put the kind of hope in their political leaders that once was reserved for God and the work of the gospel. When their political leaders are out of power, they experience a death. They believe that if their polices and people are not in power, everything will fall apart. They refuse to admit how much agreement they actually have with the other party, and instead focus on the points of disagreement. The points of contention overshadow everything else, and a poisonous environment is created. (99)

The author closes with an Epilogue where he discusses the discerning and replacing our idols. To discern our idols, Keller suggests we contemplate where our imagination goes when we’re daydreaming, where we spend our money, or where we really place our hope and salvation instead of where we profess to place it, or where we find our uncontrolled emotions unleashed. (167-9) To handle our idols, we have to do more than repent, they have to be replaced with God. I found this last part of the book to be the weakest, with just a few pages of suggestions, drawing heavily from the opening of Colossians 3. He calls for us to rejoice and repent together and to practice the spiritual disciplines as a way to invite God to replace our idolatrous desires. His final comment is an admission that this is not a onetime program, but a lifelong quest for as soon as we think we’re got our idols removed, we’ll discover deeper places within our psyche to clean out.

This book has given me much to think about. We can all benefit from what he says about the difficult to discern our own greed (52) and on how we worship success and our political ideals. Only one did I get excited about a “theological error,” and I feel pretty certain it was more from carelessness in language than in what Keller actually believes. On page 162, Keller speaks of when our “Lord appeared as a man” on Calvary, which sounds to me a lot like the Docetism heresy. Docetism held that Jesus’ humanity was an illusion. However, Keller concludes the sentence saying that Jesus “because truly weak to save us,” which sounds as if Jesus’ humanity wasn’t just an illusion.

I recommend this book and am grateful to Mr. Keller and Dutton Publishing for providing extensive notes and a detailed bibliograhy.

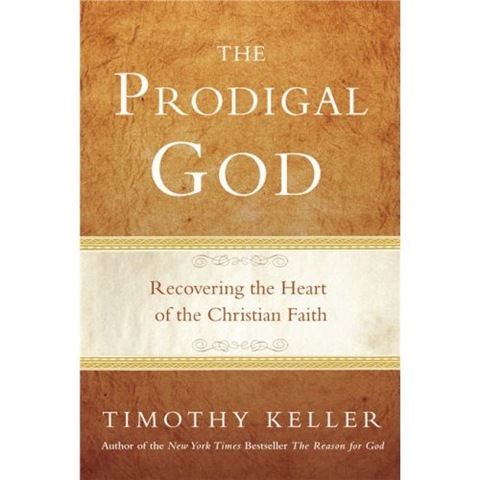

An Essay and Review of The Prodigal God: Recovering the Heart of the Christian Faith

(New York: Dutton, 2008), 139 pages.

There are two kinds of sinners, as Timothy Keller explores in this book. One kind of sinner is rather obvious. They live only for themselves, breaking God’s laws and perhaps even the laws of the land. Such sinners are represented by the younger son in Jesus’ parable of the Prodigal Son, who after wishing his father’s death so he can inherit his portion of the estate, is given his inheritance and runs off to a foreign country.

We have a love/hate relationship with the younger boy. In God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse, James Weldon Johnson captures the flavor of American-American preachers early in the 20th Century. Many of these preachers could not read and write, but the way they told stories were poetic. In a sermon on the Prodigal Son, the preacher paints a vivid picture of the young wayward son with his daddy’s inheritance burning a hole in his pocket…

And the young man went with his new-found friend,

And brought himself some brand new clothes,

And he spent his days in the drinking dens,

Swallowing the fires of hell.

And he spent his nights in the gambling dens,

Throwing dice with the devil for his soul.

And he met up with the women of Babylon.

Oh, the women of Babylon!

Dressed in yellow and purple and scarlet,

Loaded with rings and earrings and bracelets,

Their lips like a honeycomb dripping with honey,

Perfumed and sweet-smelling like a jasmine flower;

And the jasmine smell of the Babylon women

Got in his nostril and went to his head,

And he wasted his substance in riotous living,

In the evening, in the black and dark of night,

With the sweet-sinning women of Babylon.

Why is it that we are fascinated with the younger son? Certainly we’re glad that he’s redeemable, but we also relish in the visions of his sinful past. If truth be told, we’re a little jealous of his freedom. Over time, the parable has even been named for him. He’s the prodigal, the one who lavishly spends his inheritance. And we forget about that this is a parable of two sons.

Timothy Keller reminds over and over again that there are two ways to be separated from God. Yes, we can be like the younger son and live wildly. This is the popular view of a sinner and many of us have been down that road. But we can also be the dutiful son and do what’s expected of us, but deep down despise the father for whom we work. Sometimes even free-spirited younger sons can become zealous older brothers. The sins of the older son are not so evident. Such sins live in the heart where they fester and boil and eventually boil over in anger and rage. Keller makes the point that churches are filled with “older sons,” those who look down on their younger brother’s sinful ways. But these “older sons” don’t enjoy the father’s company any more than the “younger sons” who want to strike out for the territories, sowing their oats along the way. Older sons are those who give religion a bad name and make the church seem harsh and judgmental. Because of their hard hearts, they don’t get to enjoy the banquet the father throws for the return of the younger son. Instead, they sulk in anger, showing the condition of their hearts.

Prodigal means reckless extravagant, having spent everything. Keller suggests that the true prodigal in the story is the Father in the story, who represents God. God goes to great distances to restore the lost son, that even though the son has already cost him a fortune, he spends it again to reclaim the boy. Redemption is not cheap, as the older boy discovers, for he feels the father is stealing from what belongs to him in order to redeem the younger boy. He’s not gratiful at all. Keller is writing, not to call the wayward younger son home, but to remind those who have never left, the older brother, not to be so self-righteous and to look down on others. This book calls those in the church to task, asking that we not be so judgmental. It’s also a book that confirms one of the main critiques made against the church, that it is a place of hypocrites. Certainly, if our hearts are like the older brother, such a critique is justified. We should take the critique as a warning for in the story, it is the younger son, not the older boy, that experiences salvation.

This is a good, easy to read, book. It can easily be read in a sitting. I recommend it.