Joy Harjo, Conflict Resolutions for Holy Beings: Poems. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2015) 139 pages.

I picked up this book after learning that Joy Harjo has been appointed poet laureate for the United States. It’s exciting because she’s the first Native American to serve in this position. In addition to being a poet, Harjo is also a jazz musician. Her poetry blends music with longing for a home that seems evasive. In different poems, the reader is taken an “Indian school” in Oklahoma, to the hunting grounds of the Inuit people in northern Alaska, and through airports and other locals in between. She alternates between more free-form poetry to “prose poems.” Many of the poems draw the reader into the experience of modern Native Americans, who, having lost a homeland, are not sure where they belong. We also are reminded of the realities within Native communities of alcoholism and suicide. Yet, a thread of hope weaves through these poems, as we (as well as all creation) are encouraged to be blessing to others. I find her poems accessible and easy to understand. I’m sure I will reread many of them as I continue to ponder their messages. .

I picked up this book after learning that Joy Harjo has been appointed poet laureate for the United States. It’s exciting because she’s the first Native American to serve in this position. In addition to being a poet, Harjo is also a jazz musician. Her poetry blends music with longing for a home that seems evasive. In different poems, the reader is taken an “Indian school” in Oklahoma, to the hunting grounds of the Inuit people in northern Alaska, and through airports and other locals in between. She alternates between more free-form poetry to “prose poems.” Many of the poems draw the reader into the experience of modern Native Americans, who, having lost a homeland, are not sure where they belong. We also are reminded of the realities within Native communities of alcoholism and suicide. Yet, a thread of hope weaves through these poems, as we (as well as all creation) are encouraged to be blessing to others. I find her poems accessible and easy to understand. I’m sure I will reread many of them as I continue to ponder their messages. .

Archibald Rutledge, My Colonel and his Lady, (1937: Indianapolis, The Bobby’s-Merrill Company, reprinted 2017), 92 pages.

In this short book, the former poet laureate of South Carolina, Archibald Rutledge, writes a memoir of his parents. His father had been the youngest colonel in the Confederate army. His father joined the war in North Carolina (the family kept a mountain home to escape to in the summer). He was wounded three times, involved in many engagements and served as best man for General Pickett, when he married. Archibald was the youngest child of the family (for which, his father often called him Benjamin, for Jacob’s last son). He was born in 1883, nearly twenty years after his father’s military experience had ended. Rutledge was in awe of his father, whom he saw as a kind, gentle, and loving man. His father shared with him the love of all things wild-hunting and fishing and just walking in the woods. He also shared his love of the creator whom he saw revealed in nature. His mother, the colonel’s lady, was also a kind but strong woman. As her husband was often away, she had to take control as she did directing the successful efforts at fighting a fire in the great house (when water had to be drawn from the river by buckets) and shooting to scare away intruders who were looking to steal from their rice barn. She also impressed the young Rutledge with her love of books and her care of others (she often served as a medical resource in a community that often had to go without physicians).

In this short book, the former poet laureate of South Carolina, Archibald Rutledge, writes a memoir of his parents. His father had been the youngest colonel in the Confederate army. His father joined the war in North Carolina (the family kept a mountain home to escape to in the summer). He was wounded three times, involved in many engagements and served as best man for General Pickett, when he married. Archibald was the youngest child of the family (for which, his father often called him Benjamin, for Jacob’s last son). He was born in 1883, nearly twenty years after his father’s military experience had ended. Rutledge was in awe of his father, whom he saw as a kind, gentle, and loving man. His father shared with him the love of all things wild-hunting and fishing and just walking in the woods. He also shared his love of the creator whom he saw revealed in nature. His mother, the colonel’s lady, was also a kind but strong woman. As her husband was often away, she had to take control as she did directing the successful efforts at fighting a fire in the great house (when water had to be drawn from the river by buckets) and shooting to scare away intruders who were looking to steal from their rice barn. She also impressed the young Rutledge with her love of books and her care of others (she often served as a medical resource in a community that often had to go without physicians).

One interesting fact I learned about the low country was a tsunami struck South Carolina following the great earthquake in Charleston in 1886. The family was staying at their “beach home” in McCellanville, South Carolina and Archibald was only three. Suddenly the water started rushing in and his mother quickly put him and a sister on a table and went to make sure the other children were safe. The water rose several feet before rushing back out to the ocean. I knew of the earthquake and its damage, but not the coastal damage from wave action.

The Rutledge family lived on a plantation that had been in the family since the 17th Century. It survived the war (it was outside of Sherman’s march through South Carolina). Of course, by the time Archibald Rutledge was born, there was no longer slaves working the fields, but sharecroppers and those who gave a day’s work a week to “rent’ their cabins. I appreciate the way Rutledge describes his encounters with the natural world, but he does display a paternalistic view when he discusses those former slaves who lived on the plantation. This book provides a glimpse into another era and the reader should remember that its view is somewhat nostalgic and romantic. This is the third book I’ve read and reviewed by Rutledge.

Sebastian Junger, The Perfect Storm (W.W. Norton, 1997, audible 2014, 9 hours and 25 minutes.

I watched the movie, “The Perfect Storm,” many years ago, but really enjoyed the book. Junger has mastered a style used by Herman Melville. Through Melville’s novel, Moby Dick, Melville blends an exciting tale with the explanation on how the crew lived, sailed and hunted whales. Junger, in telling the story of the demise of a swordfish boat, provides enlightening detail into the method of longline fishing along with metrological details and the role the Coast Guard and other rescue groups perform when the weather turns rough. Writing about a particular weather event that occurred in 1991, he primarily focuses on the men of the fishing boat Andrea Gail. He introduces his readers to the crew and their families and the “Crow’s Nest,” a favorite bar back in Gloucester, MA, from where the boat sails. In addition to the problems faced by the Andrea Gail, which was lost at sea and never found, he speaks of some dramatic rescues that were made by the Coast Guard as they rescued three from the sailboat Satori, deal with other floundering boats such as a Japanese fishing ship, and also rescued all but one of an Air National Guard helicopter crew that ditched after a refueling attempted failed. One of the members of the crew was lost at sea. This is wonderful writing and an exciting read (or, my case, an exciting listening event). I highly recommend it.

When I was hiking the Appalachian Trail, I came into Gorham, New Hampshire for the evening. It’s a small town near the Maine border. I needed to resupply for the trail ahead. I was down to only oatmeal to eat, but I didn’t have enough fuel for my stove to even prepare that.

When I was hiking the Appalachian Trail, I came into Gorham, New Hampshire for the evening. It’s a small town near the Maine border. I needed to resupply for the trail ahead. I was down to only oatmeal to eat, but I didn’t have enough fuel for my stove to even prepare that. Having been rejected, I found myself steaming. As I left town and hiked north, I began to craft the letters I was going to write… but then I realized I was putting way too much negative energy into this situation. I decided to let it be and I never sent those letters. Had Jesus been among us hikers, I think he’d told me to do just that. Drop it. Harboring such feelings is never good. It just eats at you. We cannot control how other people react to us; we can only control how we react toward them.

Having been rejected, I found myself steaming. As I left town and hiked north, I began to craft the letters I was going to write… but then I realized I was putting way too much negative energy into this situation. I decided to let it be and I never sent those letters. Had Jesus been among us hikers, I think he’d told me to do just that. Drop it. Harboring such feelings is never good. It just eats at you. We cannot control how other people react to us; we can only control how we react toward them. Jesus is heading to Jerusalem, taking the disciples with him. The text that he “sets his face” to go to Jerusalem, a phrase echoed throughout the next ten chapters. On this journey, we learn things not mentioned in the other three gospels. Jesus is not just walking, he’s teaching and healing. But Jesus doesn’t go directly to Jerusalem. If he’d had a GPS and set the destination for Jerusalem, the machine would have been constantly squawking “recalculating, recalculating” as he wanders around. It’s in this wandering we find some of our most beloved parables, such as the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son. Along the way, Jesus stops and teaches people about who God is and how they should relate to their neighbors.

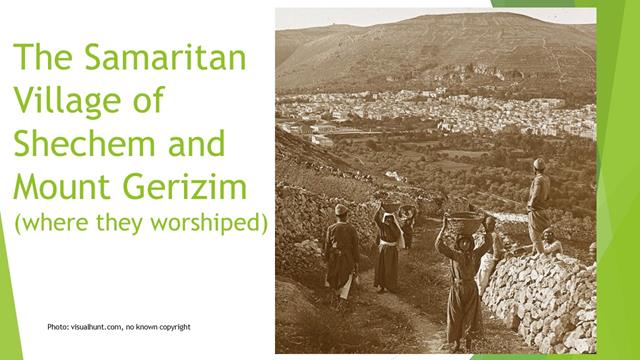

Jesus is heading to Jerusalem, taking the disciples with him. The text that he “sets his face” to go to Jerusalem, a phrase echoed throughout the next ten chapters. On this journey, we learn things not mentioned in the other three gospels. Jesus is not just walking, he’s teaching and healing. But Jesus doesn’t go directly to Jerusalem. If he’d had a GPS and set the destination for Jerusalem, the machine would have been constantly squawking “recalculating, recalculating” as he wanders around. It’s in this wandering we find some of our most beloved parables, such as the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son. Along the way, Jesus stops and teaches people about who God is and how they should relate to their neighbors. But not everyone is ready to see Jesus. Luke informs us that the Samaritans don’t want anything to do with Jesus because he has set his face towards Jerusalem. The Samaritans, who do not see Jerusalem as holy and who worship on another mountain, have grown weary of self-righteous Jews trampling through their land on their way to Jerusalem.

But not everyone is ready to see Jesus. Luke informs us that the Samaritans don’t want anything to do with Jesus because he has set his face towards Jerusalem. The Samaritans, who do not see Jerusalem as holy and who worship on another mountain, have grown weary of self-righteous Jews trampling through their land on their way to Jerusalem. Jesus doesn’t take rejection personally and encourages the disciples to get over it. Too often we forget that vengeance isn’t ours!

Jesus doesn’t take rejection personally and encourages the disciples to get over it. Too often we forget that vengeance isn’t ours!

Do we put things before Christ? Think about your life and the things you value. Are you willing to give it all up for Jesus? Is Jesus at the center of your life? Is he what’s most important?

Do we put things before Christ? Think about your life and the things you value. Are you willing to give it all up for Jesus? Is Jesus at the center of your life? Is he what’s most important?

Today, I think back to that encounter in Gorham, New Hampshire, so many years ago. I wonder what would have happened if I had gone back to that cashier at the Exxon station and apologized. I wouldn’t have to say she was right, but I could have acknowledged that my response and my thoughts about her were misguided. As humans, we can’t be responsible for what someone else does. We can only be responsible for what we do and how we react. Amen.

Today, I think back to that encounter in Gorham, New Hampshire, so many years ago. I wonder what would have happened if I had gone back to that cashier at the Exxon station and apologized. I wouldn’t have to say she was right, but I could have acknowledged that my response and my thoughts about her were misguided. As humans, we can’t be responsible for what someone else does. We can only be responsible for what we do and how we react. Amen.

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison  As a music tradition, the Blues rose out of the African American experience of slavery. In song, they cried about their plight as they longed for freedom. The song, “Go Down Moses,” captures this desire for freedom. But this tradition is found throughout scripture. For of all the Blues’ singers that’s lived, Elijah may have been the best.

As a music tradition, the Blues rose out of the African American experience of slavery. In song, they cried about their plight as they longed for freedom. The song, “Go Down Moses,” captures this desire for freedom. But this tradition is found throughout scripture. For of all the Blues’ singers that’s lived, Elijah may have been the best. “Hot Jezebel!” The queen’s name has found itself on an appetizer made of fruit preserves, horseradish, mustard and pepper.

“Hot Jezebel!” The queen’s name has found itself on an appetizer made of fruit preserves, horseradish, mustard and pepper.

Have you ever felt you were all alone in the world? That everyone was out to get you? If so, you can identify with Elijah’s plight. Twice in this passage, once even after he encounters the Lord, Elijah proclaims his righteousness and cries out about Israel’s apostasy and how all the prophets have been killed except him. It was the same cry he made in the previous chapter on Mt. Carmel.

Have you ever felt you were all alone in the world? That everyone was out to get you? If so, you can identify with Elijah’s plight. Twice in this passage, once even after he encounters the Lord, Elijah proclaims his righteousness and cries out about Israel’s apostasy and how all the prophets have been killed except him. It was the same cry he made in the previous chapter on Mt. Carmel. The Beatles hit record back in the mid-60s, “Yesterday,” comes to mind when I think about Elijah’s predicament. It a kind of a mellow blues tune that goes something like, “Yesterday, all my troubles seem so far away, now it looks like they’re here to stay. O, I believe in yesterday.” Elijah could relate to these words. Perhaps we, too can relate. In the last verse of the song there is the line: “Now I need a place to hide away.” That’s Elijah! And we’ve all been there. The glory of yesterday is gone and we need a place to hide. Elijah flees south into Judah where he’s safe from Jezebel’s reach and then goes off by himself into the wilderness where he finds a bit of shade under a broom tree and lays down to die.

The Beatles hit record back in the mid-60s, “Yesterday,” comes to mind when I think about Elijah’s predicament. It a kind of a mellow blues tune that goes something like, “Yesterday, all my troubles seem so far away, now it looks like they’re here to stay. O, I believe in yesterday.” Elijah could relate to these words. Perhaps we, too can relate. In the last verse of the song there is the line: “Now I need a place to hide away.” That’s Elijah! And we’ve all been there. The glory of yesterday is gone and we need a place to hide. Elijah flees south into Judah where he’s safe from Jezebel’s reach and then goes off by himself into the wilderness where he finds a bit of shade under a broom tree and lays down to die. While asleep, an angel brings bread and water for Elijah. Obviously, Elijah assumes this is his “last meal.” He enjoys it and then, awaiting death, goes back to sleep. Again the angel wakes Elijah. Some people just don’t like getting out of bed. Elijah’s informed that he has a long journey so he’d better eat up and get on the road.

While asleep, an angel brings bread and water for Elijah. Obviously, Elijah assumes this is his “last meal.” He enjoys it and then, awaiting death, goes back to sleep. Again the angel wakes Elijah. Some people just don’t like getting out of bed. Elijah’s informed that he has a long journey so he’d better eat up and get on the road. Elijah sets out on a forty day journey to Horeb, the mountain of God. Forty is one of those special numbers used throughout the Bible to indicate a purifying process or a time of preparation. It rained for forty days while Noah was in the ark; the Israelites wandered in the desert for forty years; and Jesus spent forty days in the wilderness preparing for his ministry… Elijah was being prepared to meet God in his forty day journey. Forty, the number that reminds us that our troubles are not always instantaneously solved.

Elijah sets out on a forty day journey to Horeb, the mountain of God. Forty is one of those special numbers used throughout the Bible to indicate a purifying process or a time of preparation. It rained for forty days while Noah was in the ark; the Israelites wandered in the desert for forty years; and Jesus spent forty days in the wilderness preparing for his ministry… Elijah was being prepared to meet God in his forty day journey. Forty, the number that reminds us that our troubles are not always instantaneously solved.

Again, a voice asks Elijah what he is doing on the mountain. Once again, Elijah cries the blues. But the Lord doesn’t grant Elijah sanctuary. Elijah is not told, “Just stay here, I’ll take care of you.” God isn’t finished with Elijah. There is still work to be done, so he’s sent back to Israel through Damascus. Along the way Elijah is to anoint the King of a neighboring nation, an illustration that the God of Elijah cares for and controls not just the events in Israel but throughout the entire world.

Again, a voice asks Elijah what he is doing on the mountain. Once again, Elijah cries the blues. But the Lord doesn’t grant Elijah sanctuary. Elijah is not told, “Just stay here, I’ll take care of you.” God isn’t finished with Elijah. There is still work to be done, so he’s sent back to Israel through Damascus. Along the way Elijah is to anoint the King of a neighboring nation, an illustration that the God of Elijah cares for and controls not just the events in Israel but throughout the entire world. This story is rich in meaning. The eerie silence is often how God reveals himself in the wildernesses of our lives. God tells us, through the Psalmist, “to be still and know that I am God.”

This story is rich in meaning. The eerie silence is often how God reveals himself in the wildernesses of our lives. God tells us, through the Psalmist, “to be still and know that I am God.” There is a lesson in this for us. All of our spiritual journeys have ups and downs. There are times we feel close to God and other times we feel as if God is far away and doesn’t care what happens. Elijah is like this. From his spiritual high on Mt. Carmel, when there was no doubt God’s spirit was with him, Elijah slips into a depression and begins to sing the blues. “It’s just me Lord, and there ain’t much I can do.” He feels so sorry for himself that he’s ready to die. So God reveals himself again to Elijah, but in a different manner, in a most common fashion: silence.

There is a lesson in this for us. All of our spiritual journeys have ups and downs. There are times we feel close to God and other times we feel as if God is far away and doesn’t care what happens. Elijah is like this. From his spiritual high on Mt. Carmel, when there was no doubt God’s spirit was with him, Elijah slips into a depression and begins to sing the blues. “It’s just me Lord, and there ain’t much I can do.” He feels so sorry for himself that he’s ready to die. So God reveals himself again to Elijah, but in a different manner, in a most common fashion: silence. Aren’t we like Elijah? There are those times when we know we’re filled with God’s spirit and we’re on a natural high and the blues seem so far away. These are the times we know God is real—they’re our Mt. Carmel experiences. But then, there are occasions when things do not go right, when we feel sorry for ourselves, and God doesn’t seem to be present. It’s during these times we need to slow down enough to listen for God in the silence. It’s in the silence that we can come to trust that God is with us always. It’s not something we can explain or even demonstrate. Its faith: faith and a longing for that which lies beyond our grasp, that which we cannot control, but without which we can’t live.

Aren’t we like Elijah? There are those times when we know we’re filled with God’s spirit and we’re on a natural high and the blues seem so far away. These are the times we know God is real—they’re our Mt. Carmel experiences. But then, there are occasions when things do not go right, when we feel sorry for ourselves, and God doesn’t seem to be present. It’s during these times we need to slow down enough to listen for God in the silence. It’s in the silence that we can come to trust that God is with us always. It’s not something we can explain or even demonstrate. Its faith: faith and a longing for that which lies beyond our grasp, that which we cannot control, but without which we can’t live.

Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison On the flyleaf of the bulletin, I placed a quote from Brian McLaren, who describes the Trinity as a divine dance.

On the flyleaf of the bulletin, I placed a quote from Brian McLaren, who describes the Trinity as a divine dance. “New and improved!” It’s a marketing cliché we hear all the time. Yet, it gets out attention. Whether it is laundry detergent, automobiles, cell phones, computer play stations or soft drinks, our ears perk up and we rush out to buy. This is also be true for churches. We start a new program, there’s a new minister, the music is new, and so forth. We’re drawn to what’s new. By the way, this isn’t anything new! Paul faced this in Greece. The Greeks coming onto the scene. When he was in Athens, Paul was given the podium to speak before the philosophers about his faith.

“New and improved!” It’s a marketing cliché we hear all the time. Yet, it gets out attention. Whether it is laundry detergent, automobiles, cell phones, computer play stations or soft drinks, our ears perk up and we rush out to buy. This is also be true for churches. We start a new program, there’s a new minister, the music is new, and so forth. We’re drawn to what’s new. By the way, this isn’t anything new! Paul faced this in Greece. The Greeks coming onto the scene. When he was in Athens, Paul was given the podium to speak before the philosophers about his faith. Paul presents himself in weakness, in fear and trembling.

Paul presents himself in weakness, in fear and trembling. Paul is affirming here the Reformed doctrine of Irresistible Grace, or as it is known in the Westminster Confession “Effectual Calling,” which acknowledges God’s hand in our belief and understanding of the work of Christ.

Paul is affirming here the Reformed doctrine of Irresistible Grace, or as it is known in the Westminster Confession “Effectual Calling,” which acknowledges God’s hand in our belief and understanding of the work of Christ. As we read in Verse 9, we can’t imagine that which God has arranged for those he loves. God’s love for the world is beyond our comprehension. The beginning of our Christian faith isn’t belief, its love!

As we read in Verse 9, we can’t imagine that which God has arranged for those he loves. God’s love for the world is beyond our comprehension. The beginning of our Christian faith isn’t belief, its love! In Ken Bailey’s commentary on 1st Corinthians, he points out how Paul is affirming the doctrine of the Trinity throughout this passage. God the Father has all things under control; in Jesus, God comes to us as a man, in a manner that we might understand; and God’s Spirit, working through our own spirit, reveals this to be true. We see the three persons of the Trinity at work here. Although Paul doesn’t use the term Trinity, through rhetorical exegesis, Bailey cites six occasions in these verses where Paul alludes to the Trinitarian concept. Bailey, who taught most of his career in the Middle East, tells of a time he was a part of a Christian-Muslim dialogue. After dinner, one evening, one of the Muslim scholars questioned him as to the Trinity, asking for his help to understand this Christian doctrine. Bailey took the scholar to this passage and spoke about God’s work as shown throughout these verses.

In Ken Bailey’s commentary on 1st Corinthians, he points out how Paul is affirming the doctrine of the Trinity throughout this passage. God the Father has all things under control; in Jesus, God comes to us as a man, in a manner that we might understand; and God’s Spirit, working through our own spirit, reveals this to be true. We see the three persons of the Trinity at work here. Although Paul doesn’t use the term Trinity, through rhetorical exegesis, Bailey cites six occasions in these verses where Paul alludes to the Trinitarian concept. Bailey, who taught most of his career in the Middle East, tells of a time he was a part of a Christian-Muslim dialogue. After dinner, one evening, one of the Muslim scholars questioned him as to the Trinity, asking for his help to understand this Christian doctrine. Bailey took the scholar to this passage and spoke about God’s work as shown throughout these verses.  One popular phrase among Presbyterians is “The Church reformed, always reforming.” It is often cited as a reason for us to change, but it has nothing to do with that and the way it is often cited leaves off an important part of the phrase that came out of the Reformation and proclaimed, “The Church reformed, always to be reformed according to the Word of God in the power of the Spirit.”

One popular phrase among Presbyterians is “The Church reformed, always reforming.” It is often cited as a reason for us to change, but it has nothing to do with that and the way it is often cited leaves off an important part of the phrase that came out of the Reformation and proclaimed, “The Church reformed, always to be reformed according to the Word of God in the power of the Spirit.”

Essentially what Schmemann goes on to say, and what Paul also says, is that we need to experience a god that is not forced into our secular beliefs, but the God who transcends all so that he might reach out to everyone in love. Paul is referring to a God that is so big he can’t be contained in our human constructs. As believers, we need to be open to God speaking in and through us. And because we love God, we should seek to do that which God loves. For that is why we’ve been created.

Essentially what Schmemann goes on to say, and what Paul also says, is that we need to experience a god that is not forced into our secular beliefs, but the God who transcends all so that he might reach out to everyone in love. Paul is referring to a God that is so big he can’t be contained in our human constructs. As believers, we need to be open to God speaking in and through us. And because we love God, we should seek to do that which God loves. For that is why we’ve been created.

For Hazel Brown

For Hazel Brown Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison  Over a period of a few weeks, a minister listened to a parishioners tell the same fish story many times. Each time the fisherman told the story, the fish took on a different dimension. Sometimes he made the fish out to be a whale and other times it seemed to be just a lively bass. Finally, the minister felt he needed to confront this fisherman about his habitual lying… After worship one Sunday, he called the man aside and told him about hearing the same story told in different ways to different listeners… “Well you see,” the fisherman explained, “I have to be realistic. I never tell someone more than I think they will believe.”

Over a period of a few weeks, a minister listened to a parishioners tell the same fish story many times. Each time the fisherman told the story, the fish took on a different dimension. Sometimes he made the fish out to be a whale and other times it seemed to be just a lively bass. Finally, the minister felt he needed to confront this fisherman about his habitual lying… After worship one Sunday, he called the man aside and told him about hearing the same story told in different ways to different listeners… “Well you see,” the fisherman explained, “I have to be realistic. I never tell someone more than I think they will believe.” You know, we can only understand and comprehend so much and it seems that in the passage I just read, Jesus overloads his disciples. He attempts to teach them about the unique relationship between him and God the Father, and our relationship to them though the Holy Spirit. From this passage we learn that our knowledge of God comes from our knowledge of Jesus Christ. Through the life of Jesus, we are able to see God. Furthermore, we learn that through prayer, obedience, and the Holy Spirit we are empowered to carry on Jesus’ work and can experience his peace. This is a passage that deals with the work of the Trinity: God as Father, Son, and Spirit. It’s a lot to comprehend, but Jesus knows his time is short and he needs to prepare the disciples for what’s ahead.

You know, we can only understand and comprehend so much and it seems that in the passage I just read, Jesus overloads his disciples. He attempts to teach them about the unique relationship between him and God the Father, and our relationship to them though the Holy Spirit. From this passage we learn that our knowledge of God comes from our knowledge of Jesus Christ. Through the life of Jesus, we are able to see God. Furthermore, we learn that through prayer, obedience, and the Holy Spirit we are empowered to carry on Jesus’ work and can experience his peace. This is a passage that deals with the work of the Trinity: God as Father, Son, and Spirit. It’s a lot to comprehend, but Jesus knows his time is short and he needs to prepare the disciples for what’s ahead. This passage starts off with Philip begging, “Show us the Father and we will be satisfied.” It’s a natural request. Philip’s descendants must have ended up in Missouri, the “Show Me State.” You know, Philip easily answered Jesus’ call at the beginning of his ministry, as John shows us in his first chapter.

This passage starts off with Philip begging, “Show us the Father and we will be satisfied.” It’s a natural request. Philip’s descendants must have ended up in Missouri, the “Show Me State.” You know, Philip easily answered Jesus’ call at the beginning of his ministry, as John shows us in his first chapter. Jesus asked his disciples to believe that he was in the Father and the Father was in him, and that his words were the words of the Father. The disciples, being normal logical people, had a hard time understanding how the Father and the Son could be the same. As they wondered, Jesus tells them to just believe, and if they couldn’t believe because of what he said, to believe because of the works that he performed. In other words, there are two ways for them to engage with Jesus’ special relationship with God. They can accept his word or be moved by his work.

Jesus asked his disciples to believe that he was in the Father and the Father was in him, and that his words were the words of the Father. The disciples, being normal logical people, had a hard time understanding how the Father and the Son could be the same. As they wondered, Jesus tells them to just believe, and if they couldn’t believe because of what he said, to believe because of the works that he performed. In other words, there are two ways for them to engage with Jesus’ special relationship with God. They can accept his word or be moved by his work. Jesus covers his relationship to God the Father because he wants to get on to what’s going to happen after he departs. After all, this is a conversation around the dinner table the night before the crucifixion. Jesus is preparing the disciples for when he’s no longer going to be present with them.

Jesus covers his relationship to God the Father because he wants to get on to what’s going to happen after he departs. After all, this is a conversation around the dinner table the night before the crucifixion. Jesus is preparing the disciples for when he’s no longer going to be present with them. If we pray to Jesus, asking the power to do something that glorifies God, then, he promises, our prayers will be answered. Jesus also promises that God’s Spirit will be with us forever. In other words, we are not abandoned. We are not alone. God is with us. And think about how this has been fulfilled over the centuries. Jesus and his band of disciples made an impact on a small corner of the ancient world, between Galilee and Judea. But within a generation, his followers were planting seeds—from India, to Ethiopia, and to Europe—that would make a significant difference. In 300 years the church would be established all over the region and from there go out into the rest of the world.

If we pray to Jesus, asking the power to do something that glorifies God, then, he promises, our prayers will be answered. Jesus also promises that God’s Spirit will be with us forever. In other words, we are not abandoned. We are not alone. God is with us. And think about how this has been fulfilled over the centuries. Jesus and his band of disciples made an impact on a small corner of the ancient world, between Galilee and Judea. But within a generation, his followers were planting seeds—from India, to Ethiopia, and to Europe—that would make a significant difference. In 300 years the church would be established all over the region and from there go out into the rest of the world. In the 17th verse, Jesus tells his disciples that they’ll be accompanied by a true friend that only they will know. It’s the Spirit that abided with the disciples after Pentecost and now abides with us. In other words, just as the Father is in Jesus and Jesus is in the Father, so we are in the Spirit and the Spirit in us. Knowing he’s not going to be around much longer, Jesus wants to assure the disciples (and us) that they (and we) will be taken care of. Through the Spirit he’ll continue to nourish our souls….

In the 17th verse, Jesus tells his disciples that they’ll be accompanied by a true friend that only they will know. It’s the Spirit that abided with the disciples after Pentecost and now abides with us. In other words, just as the Father is in Jesus and Jesus is in the Father, so we are in the Spirit and the Spirit in us. Knowing he’s not going to be around much longer, Jesus wants to assure the disciples (and us) that they (and we) will be taken care of. Through the Spirit he’ll continue to nourish our souls…. Let me point out one interesting thing here. The Spirit, as spoken of in verse 17, isn’t to us as individuals. When Jesus says the Spirit abides in you, it’s plural, not singular. In other words, the access to the Spirit is found within the fellowship of the church. It’s within the fellowship that Jesus commands us to love one another, as we abide in God through the Spirit and abide in one another through love.

Let me point out one interesting thing here. The Spirit, as spoken of in verse 17, isn’t to us as individuals. When Jesus says the Spirit abides in you, it’s plural, not singular. In other words, the access to the Spirit is found within the fellowship of the church. It’s within the fellowship that Jesus commands us to love one another, as we abide in God through the Spirit and abide in one another through love. The early disciples found comfort in Jesus’ words, and we can too. Though Jesus we can know God, and more importantly, we can be forgiven and found to be righteous so that we can enter God’s kingdom. Furthermore, it is comforting to know God’s Spirit, which was first manifested on Pentecost Day so many years ago, is still with us today, ready to lead the church into the 21st century. As a church, our life must be grounded in the Spirit that abides in us. For this reason, the church always has hope. Despite persecution or indifference from the world in which we live, we have something the world doesn’t. We have God’s Spirit, and we need to trust this gift, because it is all that matters. If we abide in the Spirit, we’ll be okay.

The early disciples found comfort in Jesus’ words, and we can too. Though Jesus we can know God, and more importantly, we can be forgiven and found to be righteous so that we can enter God’s kingdom. Furthermore, it is comforting to know God’s Spirit, which was first manifested on Pentecost Day so many years ago, is still with us today, ready to lead the church into the 21st century. As a church, our life must be grounded in the Spirit that abides in us. For this reason, the church always has hope. Despite persecution or indifference from the world in which we live, we have something the world doesn’t. We have God’s Spirit, and we need to trust this gift, because it is all that matters. If we abide in the Spirit, we’ll be okay. Rejoice, today is Pentecost. Be bold, for God is with us. Amen.

Rejoice, today is Pentecost. Be bold, for God is with us. Amen.

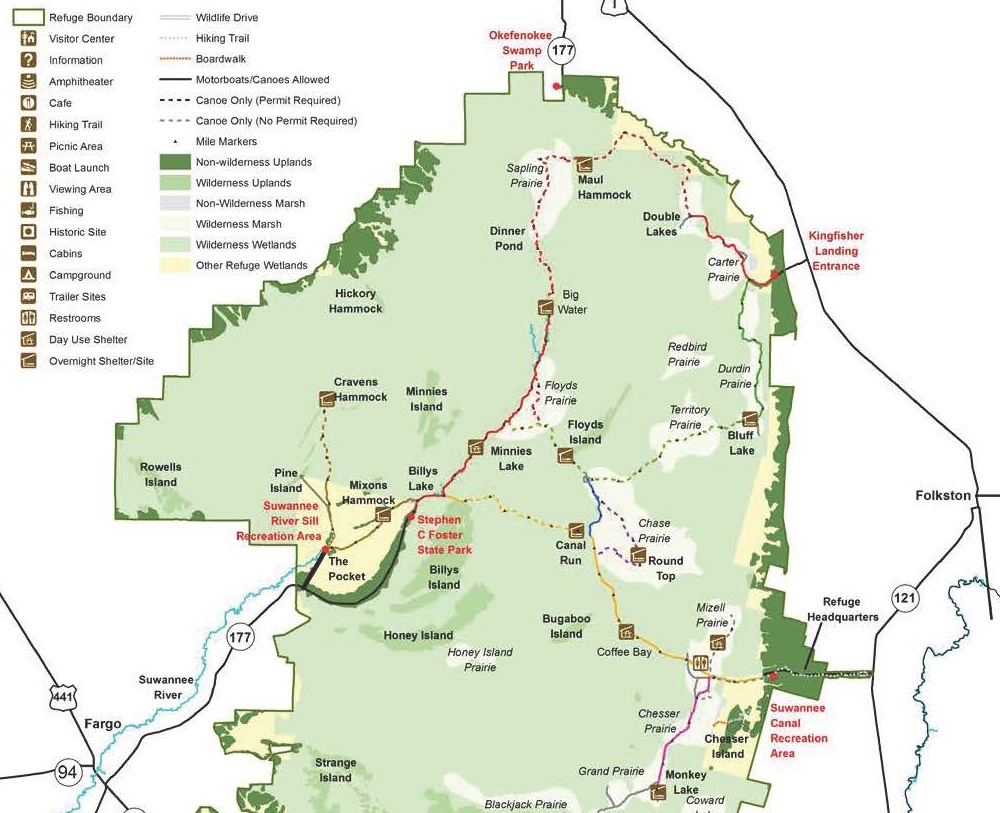

We eat lunch under the front porch during a downpour. A turkey and a fawn with spots make their way through our camp as we wait for the rain to clear. Later in the afternoon, when the storms have cleared, we move our kayaks, portaging over the quarter mile or so of the island, so that we’d be ready for the next day’s paddle. That evening, we cook over an open fire. The smoke helps deter the biting flies. We enjoy crackers and cheese, party nuts, along with some Johnny Walker Black Label. Again, I’m impressed with Gary’s beverage selection. I’m saving my cheap bourbon. Tomorrow, Gary will paddle out of the swamp while I will stay for another night.

We eat lunch under the front porch during a downpour. A turkey and a fawn with spots make their way through our camp as we wait for the rain to clear. Later in the afternoon, when the storms have cleared, we move our kayaks, portaging over the quarter mile or so of the island, so that we’d be ready for the next day’s paddle. That evening, we cook over an open fire. The smoke helps deter the biting flies. We enjoy crackers and cheese, party nuts, along with some Johnny Walker Black Label. Again, I’m impressed with Gary’s beverage selection. I’m saving my cheap bourbon. Tomorrow, Gary will paddle out of the swamp while I will stay for another night.