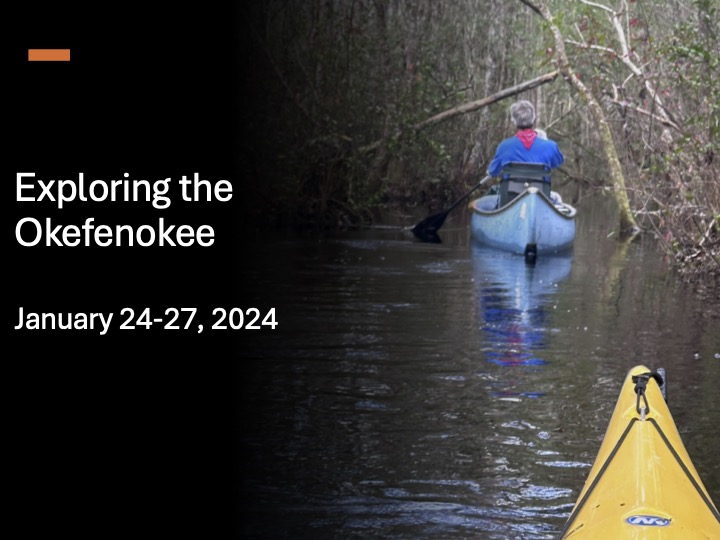

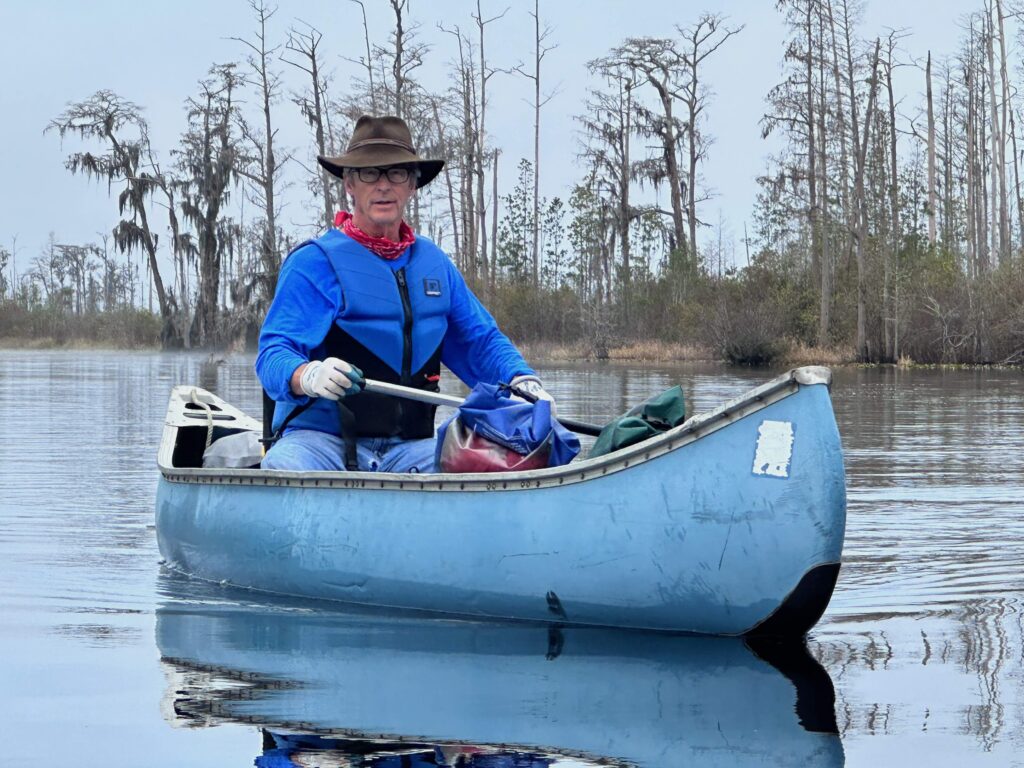

I’ve been away (taking my last week of vacation from 2023), and spending time paddling in the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. It’s a place I’ve been many times. In May 2019, I did a five day trip into the Okefenokee which you can read about by clicking here. From my count, I have spent 15 nights in the swamp and paddled in it 20 days. After my recent trip, I have paddled all the canoe trails in the wilderness area of the swamp.

Drops of water hit just above my head as I wake from a dream of helping a college student host a seminar for families who have hosted exchange students. I have no idea of the genesis of that dream, but before I attempt to process it, I need to relieve my bladder. It’s 5:15 AM. I crawl out from my hammock, realizing the rain of the last couple of hours have stopped. Water still drops from the branches of trees. The full moon has moved to the west and, with the morning fog, brings an eerie light into the swamp. The moon also reflects off the dark water of the canal. The insects, so active earlier in the evening, have quieted. In the distance, I heard a large splash followed by a squeal. Did a gator find dinner?

Bill and I are camping at Canal Run, in the heart of the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. The water in the swamp is as high as I’ve seen and flows hard toward the Suwanee. Yesterday’s paddle of a little more than 7 miles was tough, especially for Bill who paddled one of his Blue Hole Canoes.

We’d left Stephen Foster State Park on the Southwest corner of the swamp yesterday morning around 10 AM, just as the fog rose. The current as we paddled the length of Billy’s Lake wasn’t too bad and it took just an hour to make it to Billy’s Island. We stopped to explore then took an early lunch. The island has long been inhabited by humans. The Lee family lived there for 50 years in a self-sufficient homestead. They raised crops, chickens, hogs, and cows, but also lived off the wild bounty of the swamp. Sadly, having never obtained title for their land, the logging company forced them out in the 1920s. Next came a logging camp which existed for a few years while they logged the swamp of its cypress and pine. Today, the island remains uninhabited, with only a few pieces of rusting logging equipment and a cemetery remaining.

A short way up from Billy’s Island, the channel narrowed as we entered the wilderness area. From here on, motors are not allowed. We entered a quiet world. We pushed our way eastward. At times, I had to make multiple turns in my 18-foot kayak to navigate the winding narrow channel. The real difficulty was in the first couple of miles, then the old canal straightened out, allowing us to make better time. Land speculators dug the canal in the late 19th Century with the hopes of draining the swamp and opening it up to farming. The plan was to drain the water through the St. Mary’s River to the Atlantic, which was an engineering mistake as most of the swamp drains through the Suwanee River.

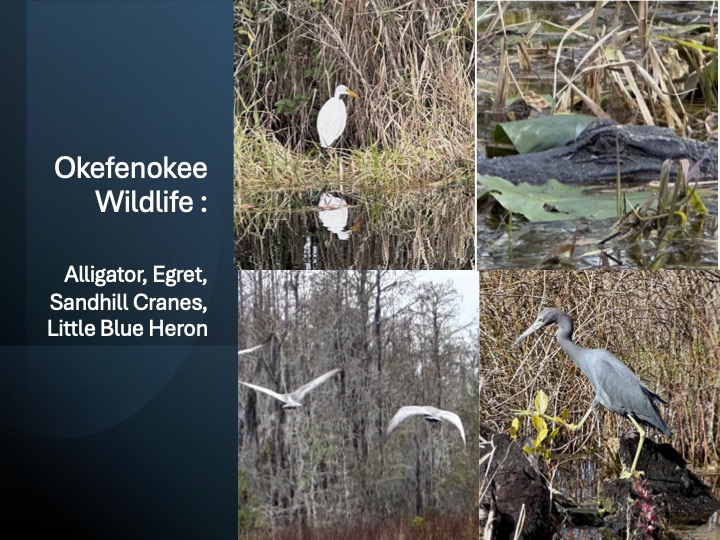

As the canal straightened and widen, I paddled ahead of Bill. Once I found the campsite, I backtracked and gave him the good news. Arriving at the campsite was a milestone for me, for it meant I have paddled all the canoe trails within the swamp. It took us four hours to make the five-mile upstream paddle from Billy’s Island. Along the way, we saw many alligators, a few turtles, a couple of cardinals, plenty of ducks, and one great blue heron.

We set up camp. Afterwards, Bill prepared the hot dogs he brought for dinner. I took his canoe and paddled upstream a bit more, collecting pieces of wood for a fire. Most of the campsites in the swamp are on platforms and fires prohibited. However, Canal Run is along the canal bank, so there is land and a campfire ring. We enjoyed a campfire and talked of folks we knew when we both lived in Hickory, NC back in the mid-80s. As we talked, the moon rose, and we could see it’s light through the trees and reflected across the waters.

We both turned in before nine, but I laid awake in my hammock for a while reading a chapter in Cecile Hulse Matschat’s Suwannee River. She had traveled in the swamp and then down the Suwannee in the early 1930s, to study orchids and came out with a handful of tales. She told about Snake Woman and her pet king snake. Some of the boys of the island caught an old rattlesnake with 21 rattlers. They let the two snakes fight it out. Everyone knew the king snake would kill the rattlesnake, but the wagers were on how long the old rattler could survive. After a chapter, I fell asleep to the night sounds of the swamp. I only woke up one before 5:15. Around 2:15, to the sound of raindrops. Checking to make sure things stayed dry, I fell back asleep to the sound of raindrops.

At 7 AM, I crawl out of my hammock and start heating water for oatmeal while perking coffee. We eat and takeour time packing up, discussing what to do next. Our plan had planned to continue down the Suwannee River, but it is so high, we know we would have a hard time finding camping spots. We discuss going down to Florida, where there are campsites up on bluffs, but when I suggest how much different the other side of the Okefenokee was than the west side, Bill decides he would like to see it.

It was just after 9 when we pushed off to make our way back to Stephen Foster State Park. The sky clears. With a warm sun, we see more alligators than the day before. We again stop at Billy’s Island for lunch. As I paddle into the boat ramp at the park, I noticed a gator with a square box on her head. Then I saw the tag on her tail with the number 209. As we pulled ashore, I ask a ranger alligator 209. “That’s Sophia,” he said. “She’s part of a study. Go to the University of Georgia’s website to learn more.”

Having packed up, we drive across the bottom of the swamp to St. Mary’s, where we picked up some ice and beer before heading north. We stop at Okefenokee Pastimes, a public campground just outside the Suwanee Canal Recreation Area. Interestingly, as I’ll later learn, the grandmother of the woman who runs the campground, was born on Billy’s Island.

After setting up camp, we plan to head into Folkston for dinner, but discover the campground has their own restaurant (serving dinner and on weekends, breakfast). We eat there both evenings and had breakfast together before we left on Saturday. I highly recommend their cheeseburger and their Philly cheese steak sandwiches. The place has a party atmosphere that includes some locals and a lot of folks from Jacksonville. We hear a lot of stories from colorful individuals including the former drummer of 38 Special. He travels around in a sleek airstream camper, and this is one of his regular campgrounds. One of the patrons even offered us a shot of “swine,” a local home brew mixture of moonshine and sweet wine. I tried it. It was okay, but not good enough to ask for a second round.

On Saturday, Bill and I set out to explore the east side of the swamp. I leave my kayak on the car and take a position in the stern of his Blue Hole canoe. This side of the swamp is more open with large swampy areas known as prairies. As the water is high, we could paddle most anywhere we wanted to go. We explored Chesser and Mizzell prairies and stop at Cedar Hammock platform. I remember taking some incredible sunset photos from here in 2015. We see lots of large birds including sandhill cranes, egrets, and hawks. There are plenty of alligators and turtles. While few of the flowers are in bloom, we see lots of dried pitcher plants, which will come back to life later in the spring. We also hear the bellowing of bull gators, which seemed a little in the year.

After paddling maybe 8 miles, we toured the Chesser homestead and hiked out to an observation tower over Chesser prairie. After dinner at Okefenokee Pastimes, we built a fire and sat around enjoying it. Bill plays guitar and we talk till bedtime. The next morning, after breakfast, Bill heads home and I head into Folkston to watch some trains, before my next adventure (which I’ll write about later).