Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church

Luke 12:32-40

August 11, 2019

A group of 12 Presbyterians spent the morning working on a new Habitat for Humanity home in Garden City. Four of us from this church, along with others from Wilmington Island and White Bluff made up the group. It was interesting to see how each person took on tasks as we put together walls. Sarah Benton, a worker from Wilmington Island, captured the willingness of the group when she proclaimed at the start: “I’m a great ‘toter.’ Just tell me what you need, and I’ll fetch it.” That’s the attitude of a committed disciple. It’s the attitude of the Psalmist who proclaims that he’s okay just being a doorkeeper in the house of the Lord.[1]

From our group, John Evans operated the saw, cutting boards to lengths needed, while Mark Hornsby attached plates connecting the interior walls with the outer wall. And before those walls were set in place, Debbie Hornsby attached insulation foam on the bottom plate. I worked with the team that built and stood the walls. It was good to see so much done. When the heat started to get to us in early afternoon, we called it a day.

Today, we’re hearing back to back readings from Luke’s gospel where Jesus instructs the disciples not to worry about things in this world, but to build up treasure in the world to come. By working for the benefit of others, we help fulfill Jesus’ expectations for us as disciples. But this passage also has a surprise for us. While we’re not surprised to hear of our need for serving God, we are told here that God wants to serve us. In the kingdom, the roles will be reversed. Read Luke 12:32-40

Did you catch what was said in the first verse I read? Let me paraphrase it. “Do not be afraid, for it is God’s pleasure to give us the kingdom!” Get that? There is no reason for worry. God wants to give us the kingdom.

But how many of us truly live life without worry? I fall short of the mark. I worry about a lot of things, just like you. We worry about our loved ones, our jobs, our retirement portfolios, our safety, our health, the health of our animals (that’s a big one for most of us don’t have them insured). The list goes on and on. We worry about the economy and the violence that seems too prevalent in our society. We worry about international politics, climate change, and sea level rise. As people, we worry. But the phrase often heard throughout scripture, whenever God or a representative of God is present, is “do not be afraid.”[2] What would it take for us not to be afraid?

But how many of us truly live life without worry? I fall short of the mark. I worry about a lot of things, just like you. We worry about our loved ones, our jobs, our retirement portfolios, our safety, our health, the health of our animals (that’s a big one for most of us don’t have them insured). The list goes on and on. We worry about the economy and the violence that seems too prevalent in our society. We worry about international politics, climate change, and sea level rise. As people, we worry. But the phrase often heard throughout scripture, whenever God or a representative of God is present, is “do not be afraid.”[2] What would it take for us not to be afraid?

Jesus follows his command not to be afraid with a message of readiness. For some of us, and at a time this included me, Jesus’ return is a reason for worry. When I was in high school, the book, The Late Great Planet Earth, was a best seller, and it seemed frightening. “Give us a little more time, God. Give us a little more time to get our ducks in the row. Let us sin a little more before we make a commitment to you, hopefully right before your glory breaks through the clouds.” Most of us wouldn’t include those concluding remark our prayer, but it’s what we’d be thinking.

As I said, our passage starts out with a wonderful promise from God about how God wants to give us good things, then it’s followed with two stories about the end of time. Our first story is based on a wedding banquet. The slaves await their master’s return so they can open the door for him and welcome him home. This is a positive parable, for those who aren’t dozing find themselves recipients of the master’s hospitality. He’s in a jolly mood after the wedding, so even though he returns in the middle of the night, the master pulls up his gown and ties it off around his waist, like a servant who needs to have freedom of movement to do his tasks. Then he has his slaves sit down and serves them dinner. This is odd behavior. The master, in the middle of the night, assuming the role of a slave in order to serve his servants. Who has ever heard of such a thing? This story, instead of encouraging us to be afraid of the Second Coming, should make us look forward to it. God wants to reward us by serving us. In scripture, the heavenly banquet is often used as a metaphor for the here-after. If we are doing God’s work when he returns (or when he calls us home), we’re promised good things.

As I said, our passage starts out with a wonderful promise from God about how God wants to give us good things, then it’s followed with two stories about the end of time. Our first story is based on a wedding banquet. The slaves await their master’s return so they can open the door for him and welcome him home. This is a positive parable, for those who aren’t dozing find themselves recipients of the master’s hospitality. He’s in a jolly mood after the wedding, so even though he returns in the middle of the night, the master pulls up his gown and ties it off around his waist, like a servant who needs to have freedom of movement to do his tasks. Then he has his slaves sit down and serves them dinner. This is odd behavior. The master, in the middle of the night, assuming the role of a slave in order to serve his servants. Who has ever heard of such a thing? This story, instead of encouraging us to be afraid of the Second Coming, should make us look forward to it. God wants to reward us by serving us. In scripture, the heavenly banquet is often used as a metaphor for the here-after. If we are doing God’s work when he returns (or when he calls us home), we’re promised good things.

The second parable is about a thief coming in the night. This parable is a bit more of a threat, for we are reminded of the uncertainty of when things will happen. Jesus reminds us that if the owner of a house knew when a thief was coming, he or she would remain awake. We’d probably be sitting in a chair, with a good view of the door, with a shotgun across our lap, ready to properly greet the intruder. But since we don’t know when a thief will pay us a visit, we must take precautions. We lock the doors. We latch the windows. We safely store valuables and pay insurance premiums.

The second parable is about a thief coming in the night. This parable is a bit more of a threat, for we are reminded of the uncertainty of when things will happen. Jesus reminds us that if the owner of a house knew when a thief was coming, he or she would remain awake. We’d probably be sitting in a chair, with a good view of the door, with a shotgun across our lap, ready to properly greet the intruder. But since we don’t know when a thief will pay us a visit, we must take precautions. We lock the doors. We latch the windows. We safely store valuables and pay insurance premiums.

These two parables complement each other. In one, we’re told to be awake, to be alert, for the Lord is coming. In other words, we’re told to be busy, doing God’s work. The second parable reminds us that we need to prepare ourselves for we don’t know when our Lord will return.

These two parables complement each other. In one, we’re told to be awake, to be alert, for the Lord is coming. In other words, we’re told to be busy, doing God’s work. The second parable reminds us that we need to prepare ourselves for we don’t know when our Lord will return.

Okay, you’re thinking. The church has been expectantly waiting for two millennia and Christ hasn’t yet appeared in glory. But I believe he will. Preparing for his coming is paramount. Furthermore, it doesn’t matter if we’ll be the one to see Christ come in the clouds or if we meet him on our deathbed or when we accidently step in front of a dump truck, the time will come that it will be too late. Preparation for our earthly demise is necessary. We’re to make our peace with God so we’ll be justified before the throne on the Day of Judgment. Furthermore, we’re then to use our talents to further God’s glory in the world as we strive to be more Christ-like.

Okay, you’re thinking. The church has been expectantly waiting for two millennia and Christ hasn’t yet appeared in glory. But I believe he will. Preparing for his coming is paramount. Furthermore, it doesn’t matter if we’ll be the one to see Christ come in the clouds or if we meet him on our deathbed or when we accidently step in front of a dump truck, the time will come that it will be too late. Preparation for our earthly demise is necessary. We’re to make our peace with God so we’ll be justified before the throne on the Day of Judgment. Furthermore, we’re then to use our talents to further God’s glory in the world as we strive to be more Christ-like.

There are two images in this passage worth understanding: girded loins (the loose outer garments tucked in so that they don’t trip up the worker) and burning lamps.[3] Each image reinforces the idea that we must be ready and active. Being a Christian is more than passively accepting Jesus; it requires us to change our lives to be more like him.

What should we take from this passage and apply to our lives today? Sure, we’re reminded, as the cliché goes, to get our ducks in order. We need to make peace with God while there is still time—before the master returns. But we also need to see there is no need to fear the second coming. The coming isn’t seen as a fearful event, but one of excited expectation, of God’s blessings!

What should we take from this passage and apply to our lives today? Sure, we’re reminded, as the cliché goes, to get our ducks in order. We need to make peace with God while there is still time—before the master returns. But we also need to see there is no need to fear the second coming. The coming isn’t seen as a fearful event, but one of excited expectation, of God’s blessings!

The first parable reminds us that we need to be ready to use what God has given us, our talents, to further the master’s work in the world. We’ve all been given talents and skills that we can use to build up the body of Christ, just as we all had different talents yesterday on the job site. Are we ready? Do we put our skills and abilities to use? Or do we sit back with the hope someone else does our part? If we chose the latter, we’re no different than the servants who played around and were not ready for the master’s return. But if we’re doing our part, then we’re promised that when Christ calls us home, we’ll find a place set for us at the table.

The first parable reminds us that we need to be ready to use what God has given us, our talents, to further the master’s work in the world. We’ve all been given talents and skills that we can use to build up the body of Christ, just as we all had different talents yesterday on the job site. Are we ready? Do we put our skills and abilities to use? Or do we sit back with the hope someone else does our part? If we chose the latter, we’re no different than the servants who played around and were not ready for the master’s return. But if we’re doing our part, then we’re promised that when Christ calls us home, we’ll find a place set for us at the table.

Even though these passages encourage us to be alert and active, we need to keep in mind as we do the work of a disciple, we are not buying ourselves into heaven nor are we striving to get a better room in the sweet bye-an-bye. We are called, as Christians, to respond to God’s grace, not to earn it. And we respond to God’s grace by creating a life that honors God and furthers the kingdom’s work in the world. Jesus, our Lord, died for us. He was the obedient servant. Through his sacrifice, our sins are forgiven, and we are freed to go out and work on the behalf of others that they too might come to experience his love. The Christian life is about forgiveness and service. It’s also not worrying about tomorrow, trusting in God’s providence and longing to experience the joy of being in God’s presence.

Even though these passages encourage us to be alert and active, we need to keep in mind as we do the work of a disciple, we are not buying ourselves into heaven nor are we striving to get a better room in the sweet bye-an-bye. We are called, as Christians, to respond to God’s grace, not to earn it. And we respond to God’s grace by creating a life that honors God and furthers the kingdom’s work in the world. Jesus, our Lord, died for us. He was the obedient servant. Through his sacrifice, our sins are forgiven, and we are freed to go out and work on the behalf of others that they too might come to experience his love. The Christian life is about forgiveness and service. It’s also not worrying about tomorrow, trusting in God’s providence and longing to experience the joy of being in God’s presence.

When things look tough in the world, when we struggle throughout our lives, remember the promise that God wants to give us the kingdom. Amen.

When things look tough in the world, when we struggle throughout our lives, remember the promise that God wants to give us the kingdom. Amen.

©2019

[1] Psalm 84:10.

[2] This phrase is heard over 70 times in scripture: from God speaking to Abram in Genesis 15:1, to the angels speaking to the shepherds in Luke 2:10, to Jesus addressing John in Revelation 1:17.

[3] Fred Craddock, Luke: Interpretation, A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching (Louisville: John Knox Press, 1990), 165.

J. Philip Newell, Listening to the Heartbeat of God: A Celtic Spirituality (New York: Paulist Press, 1997), 112 pages.

J. Philip Newell, Listening to the Heartbeat of God: A Celtic Spirituality (New York: Paulist Press, 1997), 112 pages. Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison

Did any of you get nervous as the end of a reporting terms approached when you were in school? Be honest. I certainly did. The idea of receiving a report card that had to be signed by parents was troubling, especially if I didn’t do well in a subject. It was even more troubling if I received anything less than a satisfactory mark in conduct. Personally, I never saw anything bad with my conduct, but my teachers had different expectations. It was often reflected with a “needs improvement” or “unsatisfactory” marks on my report card. I’d go home and if I only had a “needs improvement” mark would discover a few new chores. If it was an “unsatisfactory” mark, I’d find myself grounded for six weeks. Maybe Paul’s claim that freedom is not an opportunity for self-indulgence was meant for me.

Did any of you get nervous as the end of a reporting terms approached when you were in school? Be honest. I certainly did. The idea of receiving a report card that had to be signed by parents was troubling, especially if I didn’t do well in a subject. It was even more troubling if I received anything less than a satisfactory mark in conduct. Personally, I never saw anything bad with my conduct, but my teachers had different expectations. It was often reflected with a “needs improvement” or “unsatisfactory” marks on my report card. I’d go home and if I only had a “needs improvement” mark would discover a few new chores. If it was an “unsatisfactory” mark, I’d find myself grounded for six weeks. Maybe Paul’s claim that freedom is not an opportunity for self-indulgence was meant for me. Our passage today is about the God’s expectation for our lives. Paul provides us with guidance on practical Christian living. Such a life should show the evidence of spiritual fruit that centers on love. Paul begins this section by reminding us that we have been called to be free, but we should not use our freedom for our own self-indulgence. Instead, through love, we become slaves to others. Paul speaks of love as way of looking outward, always wanting what is best for the other person. It may be idealistic, but if we all lived this way, we the world would be a better place. Are we making the world better or worse? What kind of report card would you receive?

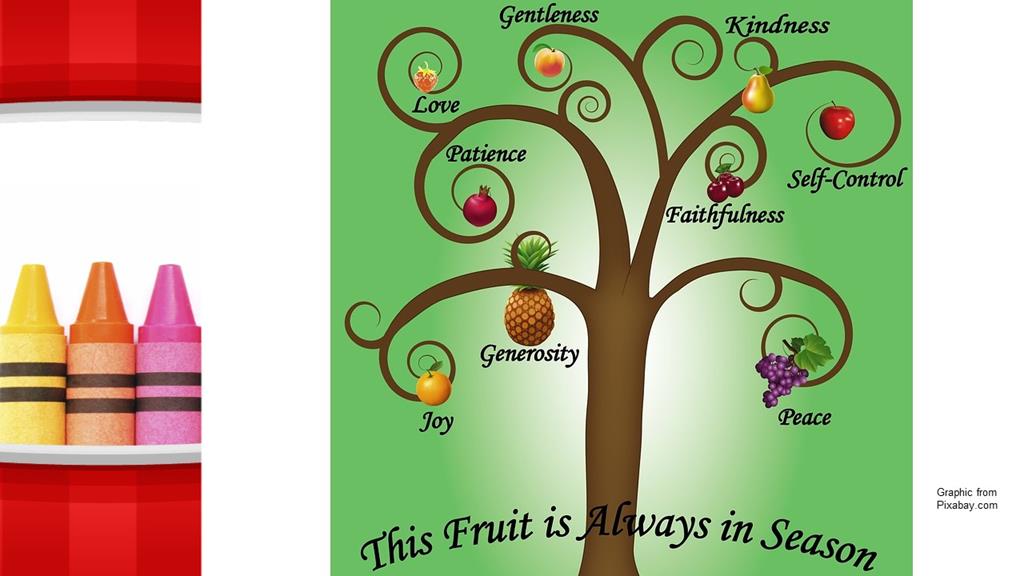

Our passage today is about the God’s expectation for our lives. Paul provides us with guidance on practical Christian living. Such a life should show the evidence of spiritual fruit that centers on love. Paul begins this section by reminding us that we have been called to be free, but we should not use our freedom for our own self-indulgence. Instead, through love, we become slaves to others. Paul speaks of love as way of looking outward, always wanting what is best for the other person. It may be idealistic, but if we all lived this way, we the world would be a better place. Are we making the world better or worse? What kind of report card would you receive? Paul draws a comparison between the types of work that come from our own desires and that which shows evidence of God’s Spirit working in our lives. The flesh can lead us down the wrong path, whether it is sexual immorality, idolatry, or creating discord within our communities. We’re to avoid such things, as Paul highlights in verses 16-22. Then, Paul provides a contrasting list of what the fruit of our life in the Spirit should look like: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control.

Paul draws a comparison between the types of work that come from our own desires and that which shows evidence of God’s Spirit working in our lives. The flesh can lead us down the wrong path, whether it is sexual immorality, idolatry, or creating discord within our communities. We’re to avoid such things, as Paul highlights in verses 16-22. Then, Paul provides a contrasting list of what the fruit of our life in the Spirit should look like: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. In this series, we’re reminded of our call to use our creativity to become better disciples of Jesus. As a disciple, the end goal isn’t to convert the world (that’s God’s work), but to be witnesses which means exhibiting such characteristics in our lives. If we were to receive a report card from God, it could have these nine items listed. How would we do? Would our grades be high enough to make our parents proud?

In this series, we’re reminded of our call to use our creativity to become better disciples of Jesus. As a disciple, the end goal isn’t to convert the world (that’s God’s work), but to be witnesses which means exhibiting such characteristics in our lives. If we were to receive a report card from God, it could have these nine items listed. How would we do? Would our grades be high enough to make our parents proud? Before we get into the individual items, let me suggest that they are to be taken as a whole. We don’t have nine different fruits of the spirit, like you might have apples and pears, bananas and pineapples. Instead, we are to have “fruit of the spirit.”

Before we get into the individual items, let me suggest that they are to be taken as a whole. We don’t have nine different fruits of the spirit, like you might have apples and pears, bananas and pineapples. Instead, we are to have “fruit of the spirit.” Now let’s look at each of these traits. Love: It’s been said that love always implies a personal investment in the object of love.”

Now let’s look at each of these traits. Love: It’s been said that love always implies a personal investment in the object of love.” The second trait we should be showing is joy. This is a hard one for we tend to think about joy as the person always smiling and laughing, forgetting the truth of that old Smokey Robinson song, “The Tears of a Clown.” We think of joy when the war is over and everyone celebrates in the street or when your favorite team wins the World Series, but such joy is fleeting. Paul encourages us to have joy even in times of trouble and persecution.

The second trait we should be showing is joy. This is a hard one for we tend to think about joy as the person always smiling and laughing, forgetting the truth of that old Smokey Robinson song, “The Tears of a Clown.” We think of joy when the war is over and everyone celebrates in the street or when your favorite team wins the World Series, but such joy is fleeting. Paul encourages us to have joy even in times of trouble and persecution. The third trait we’ll show, if we are fruitful, is peace. Again, as with joy, peace is often misunderstood. Without war is what we think peace is, but the Biblical concept is much deeper. Peace has to do with a wholeness within ourselves. It’s a state of mind that keeps us from being overwhelmed when chaos (and war) surrounds us. Peace is an outcome of knowing and trusting God.

The third trait we’ll show, if we are fruitful, is peace. Again, as with joy, peace is often misunderstood. Without war is what we think peace is, but the Biblical concept is much deeper. Peace has to do with a wholeness within ourselves. It’s a state of mind that keeps us from being overwhelmed when chaos (and war) surrounds us. Peace is an outcome of knowing and trusting God. The next trait is patience. Again, think about how we often act. We want what we can get as soon as possible. When we want to go to the store or the club or wherever we’re going, and we are impatience when we get behind a slow driver or a driver who’s lost and looking at mailbox numbers. But as a believer, we should take a deep breath. We should realize the source of our frustration, such as the slow driver, may need a break. We don’t know what is going on in his or her life. Besides, what’s the worst that might happen? We’ll be a minute late? Give the person a break and be patient is the Christian response, but one in which many of us struggle.

The next trait is patience. Again, think about how we often act. We want what we can get as soon as possible. When we want to go to the store or the club or wherever we’re going, and we are impatience when we get behind a slow driver or a driver who’s lost and looking at mailbox numbers. But as a believer, we should take a deep breath. We should realize the source of our frustration, such as the slow driver, may need a break. We don’t know what is going on in his or her life. Besides, what’s the worst that might happen? We’ll be a minute late? Give the person a break and be patient is the Christian response, but one in which many of us struggle. Kindness goes without saying. Again, God has shown kindness to us and calls us to show kindness and mercy to one another.

Kindness goes without saying. Again, God has shown kindness to us and calls us to show kindness and mercy to one another. Next comes generosity. Again, in giving His Son, God has been generous with us, and we are to therefore be generous to one another.

Next comes generosity. Again, in giving His Son, God has been generous with us, and we are to therefore be generous to one another.

Gentleness is another godly trait. Remember the parable of the forgiven servant that Jesus taught?

Gentleness is another godly trait. Remember the parable of the forgiven servant that Jesus taught? Going with gentleness is self-control. Self-control implies the discipline of an athlete; a metaphor Paul uses to describe the Christian faith.

Going with gentleness is self-control. Self-control implies the discipline of an athlete; a metaphor Paul uses to describe the Christian faith. We have witnessed God displaying all these traits that make up the “fruit of the Spirit.” Now it’s our turn to learn from life of Jesus and to show such grace to others. Doing so will make this world a better place for all God’s people. Amen.

We have witnessed God displaying all these traits that make up the “fruit of the Spirit.” Now it’s our turn to learn from life of Jesus and to show such grace to others. Doing so will make this world a better place for all God’s people. Amen.

Have you ever felt like you’re taking two steps forward and one step back? Sometimes life’s that way. It’s like climbing a cinder cone volcano. The ground is made of ash and is so unstable that you literally take two steps up and then slide back. You just hope to make progress. A 700-foot climb can take forever. But isn’t that how much of life is?

Have you ever felt like you’re taking two steps forward and one step back? Sometimes life’s that way. It’s like climbing a cinder cone volcano. The ground is made of ash and is so unstable that you literally take two steps up and then slide back. You just hope to make progress. A 700-foot climb can take forever. But isn’t that how much of life is?

Instead of letting the world shape our thoughts and actions, we’re to renew our minds by focusing on God. In John Ortberg’s book, the me I want to be (which I believe our Serendipity class studied a few years ago), we’re reminded of the power of a habit and how our thought patterns are as habitual as brushing our teeth.

Instead of letting the world shape our thoughts and actions, we’re to renew our minds by focusing on God. In John Ortberg’s book, the me I want to be (which I believe our Serendipity class studied a few years ago), we’re reminded of the power of a habit and how our thought patterns are as habitual as brushing our teeth. In Colossians, Paul encourages us to focus our minds on things above, not earthly things.

In Colossians, Paul encourages us to focus our minds on things above, not earthly things. Paul isn’t suggesting here that we have an instant change, that all of a sudden go from being Eeyore to Winnie the Pooh, from being a sourpuss to the life of the party, from being depressed to hopeful. We’re to “be transformed.” Transformation implies a process. We don’t create habits overnight, so we can’t recreate new and better habits overnight.

Paul isn’t suggesting here that we have an instant change, that all of a sudden go from being Eeyore to Winnie the Pooh, from being a sourpuss to the life of the party, from being depressed to hopeful. We’re to “be transformed.” Transformation implies a process. We don’t create habits overnight, so we can’t recreate new and better habits overnight. We need to embark on an effort to renew our minds. We need to drink deeply from the Scriptures as we read and study the Bible, individually and in groups. We need to ask God’s Spirit to guide, fill and help us learn to discern what God is doing in the world and how we can be a part of it. But we can’t just stop there. We’re not just to read the scriptures, we’re to “do something.” We practice living the life Jesus demonstrated. Unfortunately, as John Ortberg whom I quoted earlier, notes, we often debate doctrine and beliefs, tradition and interpretation, than do what Jesus said… “It’s easier to be smart than to be good.”

We need to embark on an effort to renew our minds. We need to drink deeply from the Scriptures as we read and study the Bible, individually and in groups. We need to ask God’s Spirit to guide, fill and help us learn to discern what God is doing in the world and how we can be a part of it. But we can’t just stop there. We’re not just to read the scriptures, we’re to “do something.” We practice living the life Jesus demonstrated. Unfortunately, as John Ortberg whom I quoted earlier, notes, we often debate doctrine and beliefs, tradition and interpretation, than do what Jesus said… “It’s easier to be smart than to be good.” We read God’s words, we learn God’s nature by discussing the Word with others, and we apply it to our lives… Read, Learn and Apply. Don’t be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds so that you may discern the will of God. Amen.

We read God’s words, we learn God’s nature by discussing the Word with others, and we apply it to our lives… Read, Learn and Apply. Don’t be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds so that you may discern the will of God. Amen. Jeff Garrison

Jeff Garrison  In her book, Sailboat Church, Joan Gray writes: “the church’s divine nature is not always easy to see. Sometimes it takes great faith to believe that the church as we know it is the body of Christ. Sin is all too evident in our midst.” Sounds depression, doesn’t it? But Gray continues, assuring us it’s God’s way as she continues: “the church was never meant to be a group of holy people who are in themselves morally superior to everyone else.”

In her book, Sailboat Church, Joan Gray writes: “the church’s divine nature is not always easy to see. Sometimes it takes great faith to believe that the church as we know it is the body of Christ. Sin is all too evident in our midst.” Sounds depression, doesn’t it? But Gray continues, assuring us it’s God’s way as she continues: “the church was never meant to be a group of holy people who are in themselves morally superior to everyone else.” Let me say something that might be a bit controversial. Sin abounds within the church, within Christ’s body on earth. I used to think we should try to root it out, but I no longer do. Instead, maybe we should learn from the parable of the weeds and the wheat, and not risk rooting out the weeds less we also damage the wheat.

Let me say something that might be a bit controversial. Sin abounds within the church, within Christ’s body on earth. I used to think we should try to root it out, but I no longer do. Instead, maybe we should learn from the parable of the weeds and the wheat, and not risk rooting out the weeds less we also damage the wheat.

I wonder what our life of faith might look like if we, instead of referring to God as love, referred to God as compassionate. Both are correct. God is love, but in the English language, the word “love” has lost much of its power. As many of you, I’m sure, know, the Greeks had several words for love, erotic love, brotherly love, and compassionate love. We only have one word for love and apply that word too many things. We can love our spouse, our children, a sport team, a car, a sunset, good ice cream, a pair of shoes, a song on the radio… The list continues.

I wonder what our life of faith might look like if we, instead of referring to God as love, referred to God as compassionate. Both are correct. God is love, but in the English language, the word “love” has lost much of its power. As many of you, I’m sure, know, the Greeks had several words for love, erotic love, brotherly love, and compassionate love. We only have one word for love and apply that word too many things. We can love our spouse, our children, a sport team, a car, a sunset, good ice cream, a pair of shoes, a song on the radio… The list continues. It’s often pointed out that “love” should be a verb. It should lead us to action toward that for which we have affection. It’s not just a static or emotional feeling, but is something that manifested itself in action for the wellbeing of the other. In that way, it’s like compassion, being moved to work for the benefit of the other. God is compassionate as shown in sending us his Son, to offer the human race a chance to free itself from the muck which keep us stuck and bogged down in sin. Those of us who have experienced this compassion from God are to show such compassion to others.

It’s often pointed out that “love” should be a verb. It should lead us to action toward that for which we have affection. It’s not just a static or emotional feeling, but is something that manifested itself in action for the wellbeing of the other. In that way, it’s like compassion, being moved to work for the benefit of the other. God is compassionate as shown in sending us his Son, to offer the human race a chance to free itself from the muck which keep us stuck and bogged down in sin. Those of us who have experienced this compassion from God are to show such compassion to others. The word compassion, in English, implies an awareness of another’s distress, with a desire to help alleviate that distress in some manner. It has a deeper theological meaning, as it is linked to God’s actions. In the New Testament, the word compassion is used to describe Jesus or, used by Jesus to refer to God. Paul is the one who makes the link between the compassion of God, as we see in revelation of God in Jesus Christ, to our own call to be compassionate.

The word compassion, in English, implies an awareness of another’s distress, with a desire to help alleviate that distress in some manner. It has a deeper theological meaning, as it is linked to God’s actions. In the New Testament, the word compassion is used to describe Jesus or, used by Jesus to refer to God. Paul is the one who makes the link between the compassion of God, as we see in revelation of God in Jesus Christ, to our own call to be compassionate. A modern writer defines compassion as “the knowledge that there can never really be any peace and joy for me until there is peace and joy finally for you too.”

A modern writer defines compassion as “the knowledge that there can never really be any peace and joy for me until there is peace and joy finally for you too.” Paul begins this section of his letter to the Philippians with a series of “if” clauses. This repetitiveness is tricky to translate, for we often use “if” to imply a dream. “If only this was real.” “If only this had happened…” But Paul’s use of the conditional cause doesn’t demonstrate a lack of certainty. Paul uses this litany of clauses to drive home a point. “If you believe this and if it’s made a difference in your life as it has in mine, then do this!” “If you have gotten anything out of following Christ, being in his Spirit-filled community, if you have a heart or an ounce of care, then you should act in this way.” Verse one is the lead up to how we should live as disciples, which is covered in verses 2 – 5.

Paul begins this section of his letter to the Philippians with a series of “if” clauses. This repetitiveness is tricky to translate, for we often use “if” to imply a dream. “If only this was real.” “If only this had happened…” But Paul’s use of the conditional cause doesn’t demonstrate a lack of certainty. Paul uses this litany of clauses to drive home a point. “If you believe this and if it’s made a difference in your life as it has in mine, then do this!” “If you have gotten anything out of following Christ, being in his Spirit-filled community, if you have a heart or an ounce of care, then you should act in this way.” Verse one is the lead up to how we should live as disciples, which is covered in verses 2 – 5. I love (there’s that word again) how The Message translates verse four: “Forget yourself long enough to lend a helping hand.” Paul’s talking about compassion. And then he drives this home as he tells us to be like Christ, the compassionate one. Starting with verse sixth, Paul appears to be quoting an early church hymn about Christ and he encourages us to imitate Christ’s compassion and humility. Instead of pushing and shoving and demanding that we get our “fair-share,” we’re to be Christ-like which means we lower ourselves in order to help others. In difficult situations, humility helps de-escalate tension.

I love (there’s that word again) how The Message translates verse four: “Forget yourself long enough to lend a helping hand.” Paul’s talking about compassion. And then he drives this home as he tells us to be like Christ, the compassionate one. Starting with verse sixth, Paul appears to be quoting an early church hymn about Christ and he encourages us to imitate Christ’s compassion and humility. Instead of pushing and shoving and demanding that we get our “fair-share,” we’re to be Christ-like which means we lower ourselves in order to help others. In difficult situations, humility helps de-escalate tension. You know, our lives tell a story. Whether we like it or not, how we live, what we care for, how we treat others, where we invest our talents and money, all combine to tell our story. As followers of Christ, our story will either compel others to check out our faith or it will repel them. If we realize this, it’s important that we strive to live in a way that will honor Jesus and show our trust in the Almighty. And that means to live compassionately. As one writer commented on this, “It’s not wise to name yourself as a Christian unless you are actually embodying the way of Messiah Jesus.”

You know, our lives tell a story. Whether we like it or not, how we live, what we care for, how we treat others, where we invest our talents and money, all combine to tell our story. As followers of Christ, our story will either compel others to check out our faith or it will repel them. If we realize this, it’s important that we strive to live in a way that will honor Jesus and show our trust in the Almighty. And that means to live compassionately. As one writer commented on this, “It’s not wise to name yourself as a Christian unless you are actually embodying the way of Messiah Jesus.” How might we be compassionate? We can look at the life of Jesus and live as he did? Or we might think of some of our contemporaries. Since last Sunday, we have lost a good one, a compassionate man. Jim Fendig was humble and soft spoken and concerned for others. And there are others like him within our community.

How might we be compassionate? We can look at the life of Jesus and live as he did? Or we might think of some of our contemporaries. Since last Sunday, we have lost a good one, a compassionate man. Jim Fendig was humble and soft spoken and concerned for others. And there are others like him within our community.

Are we like that? Are we closed to the possibilities of what God might do through us? Are we resistant to the abilities of Almighty God, who can do more than can imagine? Perhaps, like the man in the story, we want to keep God hidden, focusing on ourselves, even though we don’t (by ourselves) have the ability to do miracles? But, you know, when we don’t care who gets the credit, great things can happen. And if it is happening with God, even greater things can happen.

Are we like that? Are we closed to the possibilities of what God might do through us? Are we resistant to the abilities of Almighty God, who can do more than can imagine? Perhaps, like the man in the story, we want to keep God hidden, focusing on ourselves, even though we don’t (by ourselves) have the ability to do miracles? But, you know, when we don’t care who gets the credit, great things can happen. And if it is happening with God, even greater things can happen.

Our reading from the Apostle Paul’s letter to the church in Ephesus is a prayer. Paul prays his brothers and sisters in Ephesus will find strength in God’s spirit and that Christ might dwell in their hearts through faith rooted and grounded in love.

Our reading from the Apostle Paul’s letter to the church in Ephesus is a prayer. Paul prays his brothers and sisters in Ephesus will find strength in God’s spirit and that Christ might dwell in their hearts through faith rooted and grounded in love. By the way, this isn’t the only place where Paul emphasizes the importance of love. Yesterday, in the Men’s Saturday morning Bible Study, we looked at 1 Corinthians 13, which is known as the love chapter. There, Paul is insisting that the various factions within the Corinthian Church love one another. God loves us, as shown in Jesus Christ, and we are to love one another. It’s as simple as that. Even Sigmund Freud, who isn’t known for his Christian sympathies, said that we must love in order that we will not fall, and if we can’t love, illness will take over us.

By the way, this isn’t the only place where Paul emphasizes the importance of love. Yesterday, in the Men’s Saturday morning Bible Study, we looked at 1 Corinthians 13, which is known as the love chapter. There, Paul is insisting that the various factions within the Corinthian Church love one another. God loves us, as shown in Jesus Christ, and we are to love one another. It’s as simple as that. Even Sigmund Freud, who isn’t known for his Christian sympathies, said that we must love in order that we will not fall, and if we can’t love, illness will take over us.

Maybe we, as Christians, need to do more daydreaming about what it means to be the people of God. That’s what this four week study is about. God has endowed in us an ability to image new worlds. But are we willing to join with God in creating them? Or do we limit God by our own lack of imagination. We need to free God to work miracles in our lives, within our congregation and community and within our world. If we trust God, and ground ourselves in agape love, which is the type of love that calls us to work for the best of others, there’s no limit to what might be accomplished. If we trust in God’s power and are willing to creatively join God in working for a better world, there is no telling what might come out of our efforts. But if we act like things depend on what we can do and have no imagination, we risk a dark dystopia future.

Maybe we, as Christians, need to do more daydreaming about what it means to be the people of God. That’s what this four week study is about. God has endowed in us an ability to image new worlds. But are we willing to join with God in creating them? Or do we limit God by our own lack of imagination. We need to free God to work miracles in our lives, within our congregation and community and within our world. If we trust God, and ground ourselves in agape love, which is the type of love that calls us to work for the best of others, there’s no limit to what might be accomplished. If we trust in God’s power and are willing to creatively join God in working for a better world, there is no telling what might come out of our efforts. But if we act like things depend on what we can do and have no imagination, we risk a dark dystopia future.

The Israelites in exile were told to seek the wellbeing of the community in which they were living and we’re to do the same.

The Israelites in exile were told to seek the wellbeing of the community in which they were living and we’re to do the same.

Few ponder freedom more than those in prison with long days and nothing to do. Although few succeed, some spend their time creatively, attempting to obtain freedom. There were these two dudes at the Texas Correction Facility in Huntsville, who planned and watched and finally figured out if they could just crawl into the back of a delivery truck, they could possibly make it out. From observations, they learned there was this one truck that wasn’t checked as thoroughly as others. They jumped in the back, hoping they weren’t seen. Soon, the truck was beyond the walls of the prison and rolling down the highway. They waited until the truck stopped and parked. They slipped out. To their horror, this discovered they were inside the walls of another Texas prison.

Few ponder freedom more than those in prison with long days and nothing to do. Although few succeed, some spend their time creatively, attempting to obtain freedom. There were these two dudes at the Texas Correction Facility in Huntsville, who planned and watched and finally figured out if they could just crawl into the back of a delivery truck, they could possibly make it out. From observations, they learned there was this one truck that wasn’t checked as thoroughly as others. They jumped in the back, hoping they weren’t seen. Soon, the truck was beyond the walls of the prison and rolling down the highway. They waited until the truck stopped and parked. They slipped out. To their horror, this discovered they were inside the walls of another Texas prison.

Our passage begins with Jesus in the presence of some folks who had believed in him.

Our passage begins with Jesus in the presence of some folks who had believed in him.

Of course, Jesus is not speaking of political or physical freedom. And those who are listening don’t understand this. He’s using the word metaphorically, to show the power of sin to control and enslave us. In order to redirect their focus, Jesus tells them that everyone who sins is a slave to sin!

Of course, Jesus is not speaking of political or physical freedom. And those who are listening don’t understand this. He’s using the word metaphorically, to show the power of sin to control and enslave us. In order to redirect their focus, Jesus tells them that everyone who sins is a slave to sin!

Jesus tries to get people to see beyond their own self-interest by shattering our reality. He represents the truth which is not bound by anything in our material world. Jesus represents a greater reality, but can we accept him? If we accept him and live as if he is the most important thing, those things that ensnare us and entrap us may still be a threat, but they no longer have any power. If we accept Jesus and hang with him, we know that whatever happens to us, in life and in death is going to be okay for we belong to Jesus Christ.

Jesus tries to get people to see beyond their own self-interest by shattering our reality. He represents the truth which is not bound by anything in our material world. Jesus represents a greater reality, but can we accept him? If we accept him and live as if he is the most important thing, those things that ensnare us and entrap us may still be a threat, but they no longer have any power. If we accept Jesus and hang with him, we know that whatever happens to us, in life and in death is going to be okay for we belong to Jesus Christ. You know, if we accept Jesus into our lives, we must still pay the bills, go to work, and take out the trash. After all, God created us for work. It’s important that we do what we can to earn our daily bread and to offer up our labors for God to bless. Doing so, we’re freed from thinking what really matters are those things we worry about day in and day out. In the grand scheme of things, they don’t matter. We’re freed from looking out upon the world and seeing it as something to be conquered or earned. That’s not Biblical. Instead, we’re free to look out upon the world and accept it as a gift from a gracious God. And most importantly, we’re free from the guilt and shame of our past. Sin no longer eats at us because we’ve been accepted by Jesus. And, unlike our freedom, Jesus’ offer is something no one can take away.

You know, if we accept Jesus into our lives, we must still pay the bills, go to work, and take out the trash. After all, God created us for work. It’s important that we do what we can to earn our daily bread and to offer up our labors for God to bless. Doing so, we’re freed from thinking what really matters are those things we worry about day in and day out. In the grand scheme of things, they don’t matter. We’re freed from looking out upon the world and seeing it as something to be conquered or earned. That’s not Biblical. Instead, we’re free to look out upon the world and accept it as a gift from a gracious God. And most importantly, we’re free from the guilt and shame of our past. Sin no longer eats at us because we’ve been accepted by Jesus. And, unlike our freedom, Jesus’ offer is something no one can take away.