I’ve been quiet on social media lately, especially in blogland and on Facebook. Let me explain. I have also not posted any sermons recently as I have been away from the pulpit. This has been a time of reflection and change, which came to a head this past Monday, May 6, around 11:30 PM. That’s when my brother called from hospice to let me know our dad had died.

As you may imagine, I didn’t get much sleep the rest of the night, and was up way before sunrise to walk the beach (I was staying in Kure Beach). As the sun rose, I remember all those times being with Dad on the boat running out of Carolina Beach, Masonboro, or Barden’s Inlet as the sun rose. Dad’s timing always seemed perfect as we headed out toward the sun for a day of fishing. Of course, there were other days with rain or fog… But now, they’d be no more of those adventures.

On April 30, my father had his fourth intestinal surgery in twelve days. The first surgery was on Thursday, April 18. I was in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan at the time. My dad came out of the surgery doing well and things were looking up. We had several conversations by phone. He expected to get out of the hospital in four or five days. But before this happened, his intestines started to leak and there were infections. The next Thursday, he had the second surgery. They were not able to do everything, so they scheduled another surgery for Sunday and kept him sedated. There would be one more surgery for Tuesday morning, April 30. I arrived in time to meet the surgeon as he met with my brother, sister, and me. While he expressed hope, he also warned us that our father couldn’t survive another intestinal surgery.

On Wednesday, they removed the respirator and Dad slowly woke up. Things looked even better on Thursday morning, May 2. I was there first thing that morning and when the doctors and staff made their rounds. They discussed moving Dad from ICU to a step-down unit that afternoon. Later in the morning, my brother came in to relieve me. I went out to have coffee with Billy Beasley, a friend of mine whose friendship goes back to my elementary school days. While there, I got an urgent text from my brother to come back, that Dad’s intestines were leaking. Over the next hour, we learned there was nothing more they could do. Dad understood what was happening and with my brother Warren and I on each side of the bed, sniffling, he told us not to cry. He later thanked us for being there and for being good boys. They moved Dad that afternoon to hospice, where he spent the next five days.

Thankfully, the first two days, Dad did well and was able to see a lot of friends and family members. My younger brother was even able to make it in late Friday night from Japan. One of the highlights during this time was one of the visits of the pastor of his church. He is relatively new and thank my father for all he did to support his ministry and how he checked in on others within the congregation. My father said, “that’s what we’re supposed to do.

By Saturday, May 4, Dad began to slip and mostly slept. Once, he woke up enough to say, “That was nice,” after I prayed over him. They had to keep increasing morphine to keep his pain under control. Although a strong man, fate took over. Yet, it took him a long time to give up. He would eventually stop breathing when alone (my brother was in the room but asleep).

Probably ten years ago, my father had me write an obituary for him and my mother, Barbara Faircloth Garrison, who died in 2020. I pulled out the obituary from my files, updated it (mostly increasing the number of great-grandchildren), and began editing it with my siblings. Below is the final product:

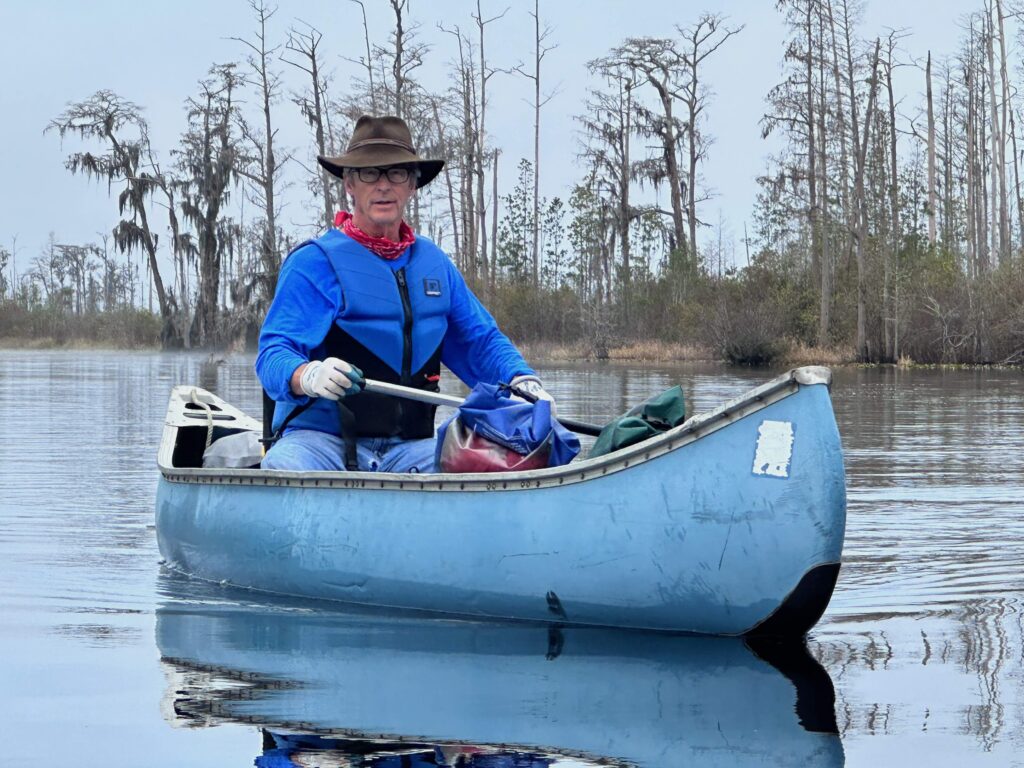

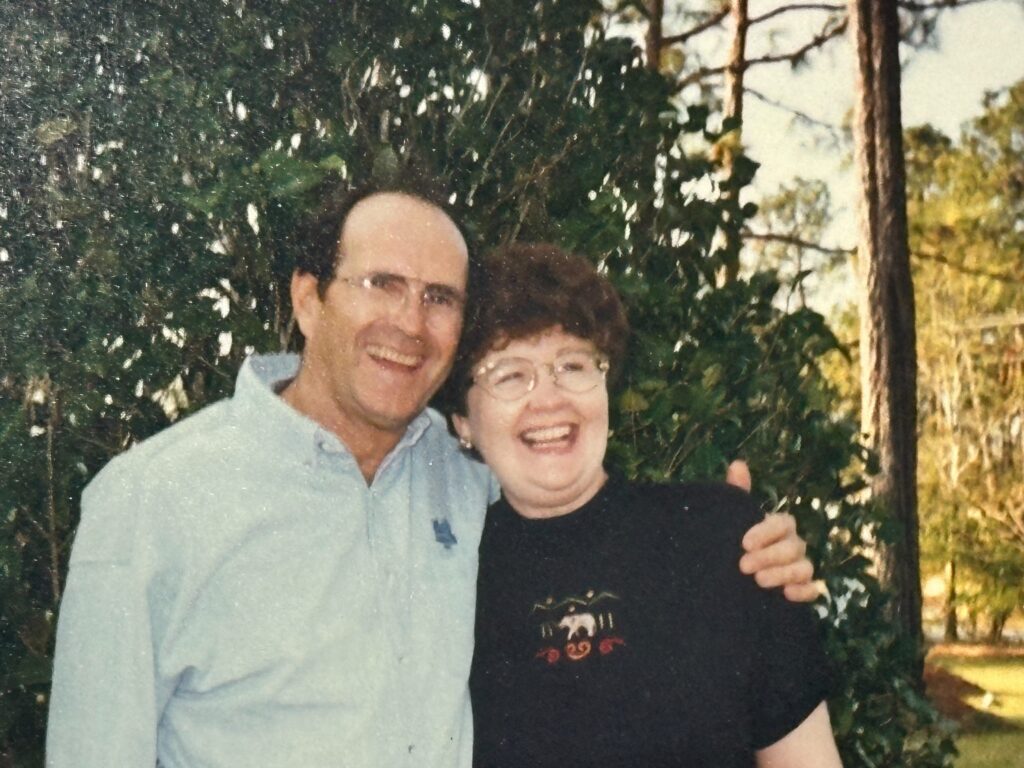

Charles Albert Garrison died on May 6, 2024 from complications following intestinal surgeries. Charles loved being on the water and never felt more alive than when he was out on his boat or fishing. He and his late wife were known for their love for each other and their hospitality toward others, including annual New Year Eve oyster roasts.

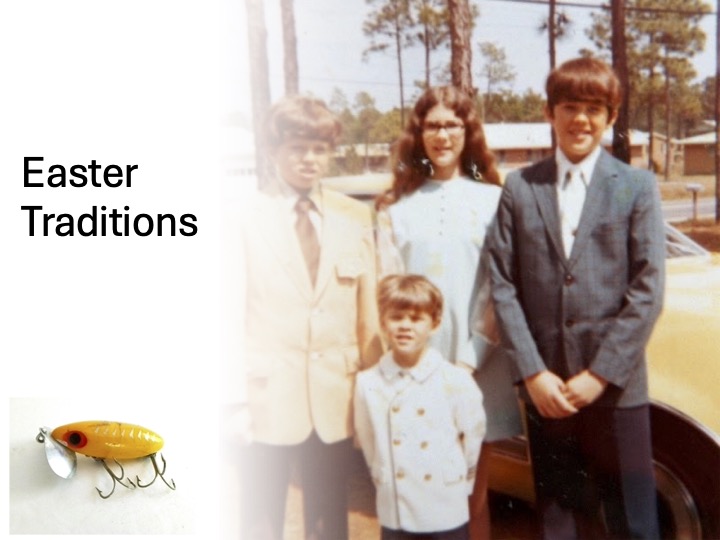

Charles was born on December 29, 1936 in Pinehurst, North Carolina to Helen McKenzie and A. H. Garrison. He was an Eagle Scout and while a high school student played football, basketball, and baseball. In 1955, he graduated from Pinehurst High School and two months later, on July 29th, married Barbara Jean Faircloth. Their marriage lasted 65 years, till Barbara’s death in 2020. Together, they had four children: Charles Jeffrey (Donna), Warren Albert (Sheri), Sharon Kaye and David Thomas (Monica).

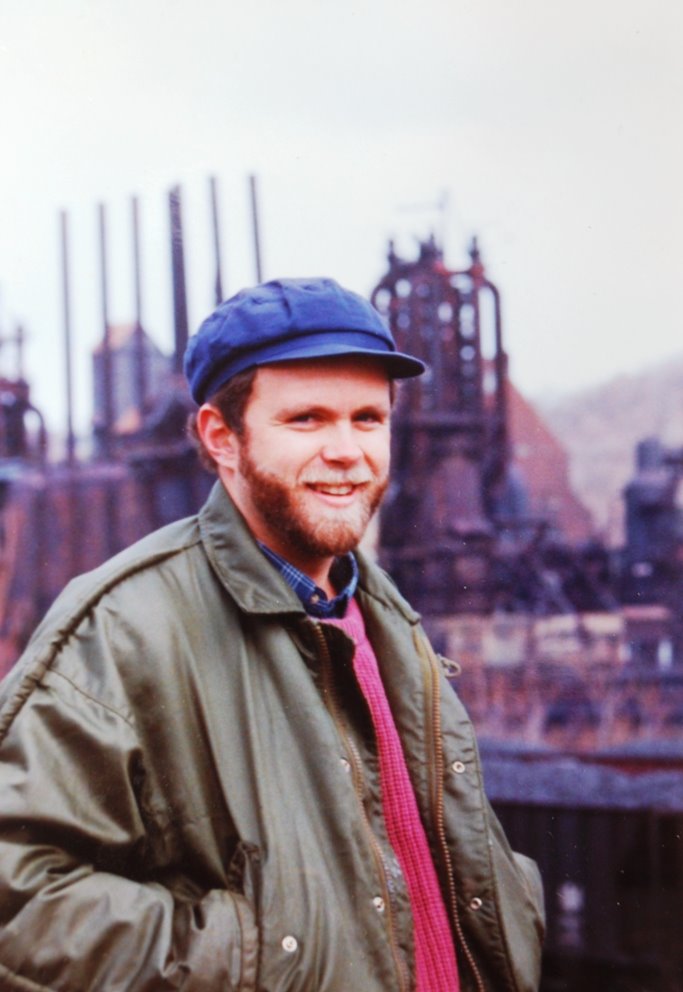

In 1962, Charles went to work for the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. He was employed by the company for the next forty years. He began his career in Petersburg, Virginia in January 1963. In 1966, he jumped at the opportunity to move to Wilmington, North Carolina where he could be near the ocean. He would live the rest of his life in Wilmington except for two overseas assignments in Japan and Korea. During his career with the company, he was an insurance inspector, an ASME Code Inspector for Boilers, Pressure Vessels, and a Nuclear In-Service Inspector. He retired from Hartford in 2002 but continued to do consulting work for another five years. He finally gave up working to care for his wife.

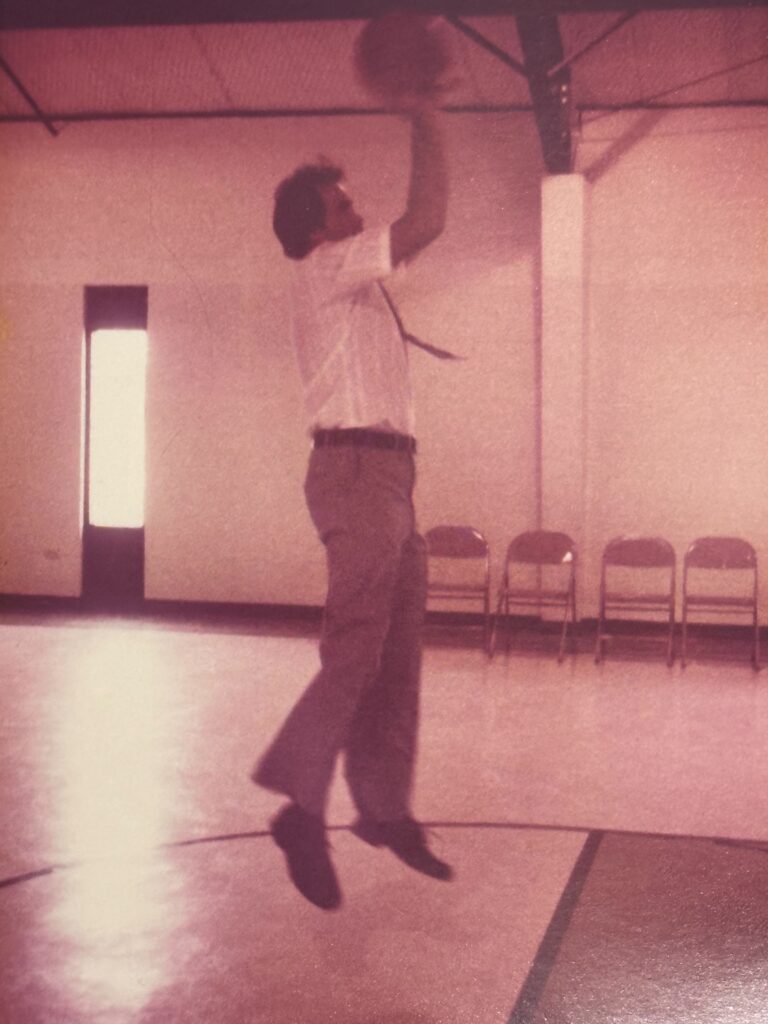

Charles remained active throughout his life. In his younger years, he hunted and fished, played basketball and softball. Once he moved to Wilmington, he continued to play softball for a few years and limited his basketball to outside pickup games with his sons and their friends. He devoted as much time as possible to fishing. He often spent weeks in the fall of the year camping and fishing on Masonboro Island. Later, he would make a sojourner of a week or so to Cape Lookout, where he would camp and fish with family and friends.

The church was always important to Charles. Like his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, he was a Ruling Elder in the Presbyterian Church. He served on many committees, especially the building and grounds committee at Cape Fear Presbyterian Church, where he remained a member for 58 years. Charles attended church every Sunday he was able. He and his wife made many friends at Cape Fear and often visited new families within the church. They also delivered tapes of the church services to shut-ins within the congregation.

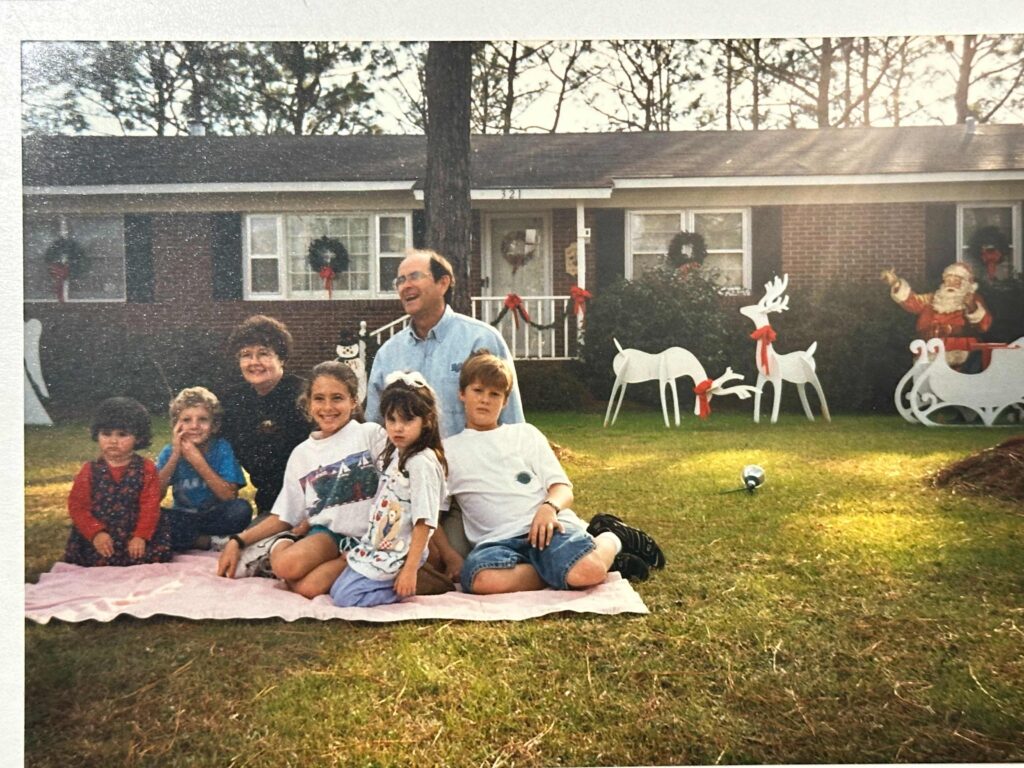

Charles was a craftsman and handy man. He restored a home in Pinehurst and added on to his home in Wilmington. In high school, he made his future wife a cedar chest which they used for the rest of their lives. An excellent welder, he built the basketball goal which still stands in his yard. His great-grandchildren now play basketball on this goal. He also welded a Christmas tree stand out of steel that would have survived a nuclear war (the tree might have snapped off, but the steel stand wasn’t going anywhere). Charles was also known for his handmade wooden Christmas decorations including a sleigh and reindeer which populated his front year during the season. He also built many Rudolph the Red-nose Reindeer door hangers and poinsettias holders which he gave away as gifts.

Charles also served as a leader in the Boy Scout program when his sons were in scouting and helped coach baseball. Charles continued to enjoy attending the ball games of his children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren. He also served for many years as a Myrtle Grove Volunteer Firefighter and as a Gideon.

Charles was preceded in death by his parents, a sister (Martha Kay), and his wife. In addition to his children, he is survived by his brother Larry (Louise), his four children, seven grandchildren (Craig, Kristen, Elizabeth, Jonathan, Clara, Thomas, and Caroline), twelve great-grandchildren, a niece (McKenzie), and many cousins. For the last three years he enjoyed the company of Ginny Rowlings and her family. They spent many evenings at the NC Symphony, concerts and plays and eating ice cream.

In lieu of flowers, memorials may be made to Cape Fear Presbyterian Church and the Lower Cape Fear LifeCare of Wilmington (hospice). A graveside service will be held at Oleander Memorial Gardens on Monday, May 13, 2024 at 2 PM. The Rev. Aaron Doll of Cape Fear Presbyterian Church will officiate. Charles will be buried by his wife in a plot they picked out and where his body will lie in rest near the salt water he loved and where, at high tide, it might even tickle his toes.[1]

Some more “Dad Stories:

Four days in the Dry Tortuga’s

Lessons from Dad (with some great photos)

Lumber River Paddle (my last great adventure with Dad)

Fishing off Cape Lookout, 2020

Dad’s 85th Birthday (and my last time paddling with him)

[1] Some might wonder about this last line, so let me explain. My parents brought cemetery plots in the 1980s, after coming back from Japan. His mother (my grandmother) wanted to know why he wanted to be buried so far away and not with the rest of the family at Culdee Presbyterian Church in Moore County. My father told her that he wanted the salt water to tickle his toes during high tide. My grandmother didn’t think it was funny, but I Dad (and I) got a laugh out of it.